1 INTRODUCTION

Institutional theory has been one of the key theories in several research areas, such as social sciences (Scott, 1987), institutional economics (North, 1990), international business (Meyer, 2001; Peng, 2002), and management (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983). However, research in tourism using institutional theory as main argument is still incipient, with few exceptions (Pavlovich, 2003; Wilke & Rodrigues, 2013). In this paper, we propose how institutional theory and its ramifications explain tourist flows, destination image, and the fit between the tourists' image of the destination and that of residents.

Institutional theory has several components that can be used to better understand the logics behind tourism using an alternative view. It is important to point out that institutional theory is an evolving theory. Tourism is a field that can be examined through neo-institutional theory - analyzing homogenization of practices and structures among entities (Meyer & Rowan, 1977; DiMaggio & Powell, 1983). Specifically, isomorphism explains why entities take similar actions and assume similar shapes based on institutional pressures (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983). Hence, isomorphism can explain elements of destination communication and marketing strategies that are common to various destinations.

On the other hand, in a more recent form, institutional theory can explain the diversity of responses of entities to institutional pressures (Greenwood et al., 2008). Hence, institutional logics and institutional fields emerge as possible ways to explain strategies in tourism. There is an opportunity for analyzing tourism as a field that still has space for homogenization of 'good practices' or a field that responds to several publics and logics. As there are several institutional logics in tourism, for instance, local social issues, local culture, different nationalities, and cultures from visiting tourists, a long and diverse chain of organizations in the industry, governments, and even religion (Scott, 1987, Friedland & Alford, 1991). This configuration of elements makes tourism a field with high institutional complexity. This complexity can be composed of competing or complementary logics, which requires a set of strategies and actions as a response to this complexity (Greenwood et al., 2015).

Institutional decoupling happens when organizations decouple their formal structure from their activities to preserve legitimacy to the institutions of the environment (Meyer & Rowan, 1977). The common disassociation between the image of a destination that tourists have and the image that the local population has can be alternatively explained by institutional decoupling. Institutional hybridization, on the other hand, explains how firms cope with institutional pressures from different agents (Besharov & Smith, 2014). Hence, tourism research can use hybridization to understand conflict resolutions between local population interests and destination strategies. Institutional categorization can be used to explain how entities can change the meanings of cultural categories (Ocasio et al., 2015). By using categorization, tourism researchers can explain the changes in image promoted by destination strategies.

Thus, in this paper we give some insights into how institutional theory can explain strategies in tourism. Specifically, we show the incipient nature of institutional theory in tourism and how the theory can be used in this field. The guiding question of this paper is "how can tourism research use institutional theory?" We develop our main argument about institutional theory having been underexplored in the tourism field by using bibliometric analysis. Then, we show some possible applications of institutional theory to explain tourism phenomena using propositions.

This paper is divided into four sections other than this introduction. First, we provide a literature review that has the basic developments of institutional theory (neo and old) and bibliometric analysis that shows how institutional theory has been used in tourism research. In the propositions section, we show how five key elements of institutional theory (legitimacy, isomorphism, decoupling, hybridization, and categorization) can be used in a broad sense to investigate issues in tourism. Finally, in the discussion and conclusion sessions, we show the main contributions of using institutional theory in tourism research and show a series of research avenues that can be opened by this possibility.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Old and Neo-institutionalism

Often the term institution is used as synonymous with organization, company, among others. However, this equivalence between terms becomes dangerous when addressing the issue of institutionalism. In this case, institutions should be seen as shared and socially constructed rules from the various interactions and negotiations over time that will guide future interactions and negotiations (Barley & Tolbert, 1997). In addition, institutions are elements that generate stability (Selznick, 1996), since they generate an expectation of future actions and behaviors (Barley & Tolbert, 1997; DiMaggio & Powell, 1983; Haveman, 1993) and are expected to be perennial over time (DiMaggio & Powell, 1991).

An early concept for institutional theory, according to Scott (2014), is that both current actors and events are, for the most part, shaped by the actions and fruits of the past. It is worth noting that the author makes this statement about the evolution of institutional theory itself, as a theory construction. However, this assertion is also valid for an initial attempt to conceptualize what institutional theory is. The replication of past actions several times can generate norms and rules, formal or otherwise, that are incorporated into everyday life, generating new future patterns (Meyer & Rowan, 1977, Scott, 2014, Thornton, Ocasio, & Lounsbury, 2012).

Scott (2014) identified three pillars that make up the institutions: regulative system, normative system, and cultural-cognitive system. In this division, the regulative system is composed of laws and rules whose fulfillment, or not, generates rewards or sanctions and its main actors are the states and agencies. In turn, the normative system creates standards that must be followed and are sources of legitimacy to the same group with common interests and is commonly associated with the professions. Finally, the cultural-cognitive system concerns shared meanings that give meaning to social life, actions that are in accordance with these shared meanings are also sources of legitimacy (Scott, 2014, Thornton et al., 2012). Frame 1 details these pillars and their components.

Frame 1 Three pillars of institutions

| Regulative | Normative | Cultural-Cognitive | |

| Basis of compliance | Expedience | Social Obligation | Taken-for-grantedness, Shared understanding |

| Basis of order | Regulative rules | Binding expectations | Constitutive Schema |

| Mechanisms | Coercive | Normative | Mimetic |

| Logic | Instrumentality | Appropriateness | Orthodoxy |

| Indicators | Rules, Laws, Sanctions | Certification/Accreditation | Common beliefs, Shared logics of action, Isomorphism |

| Affect | Fear, Guilt/Innocence | Shame/Honor | Certainty/Confusion |

| Basis of legitimacy | Legally Sanctioned | Morally governed | Comprehensible, Recognizable, Culturally supported |

Source: Scott (2014)

Institutions can be seen both as supra-organizational patterns by which individuals conduct their material life and locate it in time and space, as well as a system of symbols by which individuals categorize and give meaning to their activities (Friedland & Alford, 1991). Thus, we can say that institutions are composed of symbolic elements, social activities, and material resources (Scott, 2014).

These norms and rules can be divided into practices, models, and policies to be followed (Pacheco, York, Dean, & Sarasvathy, 2010). Institutions can normally be seen as normative, laws, for example, but as a social fact, in the sense proposed by Durkheim, as ways of acting, thinking and feeling that are external to individuals and that have great power of coercion (Durkheim, 2013), which must be taken into account by the actor in their actions (Meyer & Rowan, 1977). In this sense, institutions partially manage conflict resolution, mediating individual socioeconomic interests against collective rules (Mantzavinos, 2011). For Mantzavinos (2011), the main reason and function of institutions is to be a solution to the problems and social conflicts.

Institutions also have the function of structuring daily actions, giving meaning to social life and reducing uncertainties (Kalantaridis & Fletcher, 2012). That is, in addition to their normative and coercive aspects, institutions produce meaning for life and social structure, their cultural-cognitive aspect (Scott, 2014). In this way, the institution can be considered something limiting and deterministic, even though, by nature, institutions are resistant to change (Giddens, 2009). However, this limiting and deterministic character does not fully define the term institution, because for Machado-da-Silva et al. (2010) beyond regularities, institutions produce possibilities, since, for these authors, the institution is also a condition for the existence of relationships between social structure and agency. For Barley and Tolbert (1997), these norms will generate behaviors with different degrees of conformity with them, that is, not all norms will be accepted in the same way by all. Moreover, this set of rules allows actors to interpret social phenomena in their own way and act according to this interpretation (Kalantaridis & Fletcher, 2012).

Based on the definitions presented and these dichotomies between the institution being something deterministic and, at the same time, something that generates the changes, it is worth to expose the differences between new and old institutionalism. While the former focuses on influence, coalitions, values, power, and informal structures occupying a central position (Selznick, 1996), the new one considers legitimacy, its insertion into its organizational fields and classifications, routines, norms occupying a central position (Greenwood & Hinings, 1996). For DiMaggio and Powell (1983), this new institutionalism is a source, or continuity, for the Weberian bureaucracy. In fact, the new institutionalism has shifted the culture-dominated focus to the notion that rational actors are limited in their actions by institutionalized practices in their organizational field (Beckert, 1999) in both focuses, but the new institutionalism has a deterministic character, according to Machado-da-Silva et al. (2010).

Still on the distinction between old and new institutionalism, Machado-da-Silva et al. (2010) do not agree that the former is geared towards change, for the emergence of new standards, while the latter focuses on the maintenance and permanence of what already exists and on the non-action of the actors and suggest an agency look at the Institutional theory. In keeping with the definitions of Bandura (2006) and Emirbayer and Mische (1998), maintaining the standards may be an intended goal and, as put by DiMaggio and Powell (1983), be equal facilitates the legitimacy of the action or organization.

For Clegg (2010), institutional theory brings back issues of power and agency and places the concept of auditory society, that is, it places legitimacy at the center, which is a central point of neo-institutional theory (Machado-da-Silva et al., 2010). In other definitions the authors seek to explain the actions of firms to make sense or justify their movements (Suddaby, 2010).

Legitimacy can be understood as the general expectation that an action is in accordance with legal, moral or model assumptions or with socially and culturally constructed roles (Scott, 2014). Legitimacy is central to the isomorphism proposed by DiMaggio and Powell (1983), in which organizations exhibit similar behaviors and replicate models known as a quest for legitimation. This legitimacy guarantees the company access to different resources and is associated with better performance in several studies (see Heugens & Lander, 2009)

If, on the one hand, legitimacy guarantees the maintenance of institutions, it is also a key concept in institutional change, since questioning the institution begins by questioning its legitimacy (Machado-da-Silva et al., 2010). Even in older institutions, their own contradictions over time may result in a loss of legitimacy (Greenwood & Suddaby, 2006).

While institutions limit and direct behaviors, they also differentiate between groups of individuals, giving different powers, privileges, roles, and responsibilities to different actors and stakeholder groups (Scott, 2014). In this way, this differentiation and, in a sense, imbalance, offers opportunities for new forms that alter these configurations and, consequently, changes occur (Owen-Smith & Powell, 2008, Scott, 2014).

2.2 The new "new institutionalism"

Institutional theory has been evolving over time, gaining ground from the old institutionalism to the new institutionalism. However, the new institutionalism itself has been changing and gaining new themes. One of these themes is institutional logic, which can be considered as the broad set of beliefs that define the boundaries of a field, as well as roles and identities, and organizational arrangements (Suddaby & Greenwood, 2009). In addition, institutional logic acts as a guide to practical actions (Rao, Monin, & Durand, 2003), which are common to participants in the same field (Owen-Smith & Powell, 2008). That is, agents give meanings to actions and delimit these actions in time and space through or under the influence of institutional logics (Thornton et al., 2012).

To illustrate how institutions shape practices and give meaning to them, Friedland and Alford (1991) propose institutions being composed of subsystems called institutional orders, which perform the same functions of institutional logics and can be used synonymously (McPherson & Sauder, 2013 and Thornton et al., 2012). The interrelationship between these various logics that will act on individuals and organizations, not just one at a time, will give meaning to their actions and shape their cognition and behavior. Thus, an organization, or individual, can be influenced by more than one logic, generating different meanings, beliefs, and practices according to the dominant logic at that time (Greenwood, Raynard, Kodeih, Micelotta, & Lounsbury, 2011; McPherson & Sauder, 2013), so that there is no uniformity of responses of organizations and individuals in a same context (Greenwood, Diaz, Li, & Lorente, 2010).

Most studies on institutional logic have focused on understanding how institutional logics work at their macro level, influencing the institutions, strategies, and practices of organizations within these institutions (McPherson & Sauder, 2013). Little attention has been given to how institutional logics affect the actions of actors in their daily lives and their daily practices (Currie & Spyridonidis, 2016; McPherson & Sauder, 2013). In this case, it is first noticed a recognition of actors' agency, unlike the deterministic view of neo-institutionalism, that is, actors will act not only on the influence of these diverse logics, but on their interpretation and how to reach their objectives in this field (Delbridge & Edwards, 2013, Emirbayer & Mische, 1998).

At its micro level, institutional logics are highly related to the individual's social position. In a more prominent position, the actor has the possibility to influence the interpretation of the institutional logics that people in the position of minor will do (Currie & Spyridonidis, 2016). In addition, the centrality of their position, the greater their capacity to lead to change, and the more peripheral their social position, the greater the cost to escape institutional pressures (Currie & Spyridonidis, 2016).

Meeting the definition of agency by Emirbayer and Mische (1998) as the individual action that happens through a temporally embedded process of social engagement, derived from past interactions and habits, oriented toward the future through the visualization of alternative possibilities. Recent research indicates that institutional logics reinforce that the individual's relations with institutional logics in the past will not only define their interpretation of new logics in the future, but also how to deal with these logics and the desire to modify them (Bertels & Lawrence, 2016).

The institutional logics themselves are the basis for new emerging issues in institutional theory. Issues such as institutional complexity and will seek to analyze how organizations respond to environments composed of divergent and competing institutional logics (Greenwood et al., 2011). One way to deal with this competition of logics is by constructing identities that meet the expectations of a particular logic (Reay & Hinings, 2009). However, this dichotomous view between meeting one and not meeting another is opening space for a vision in which one seeks to filter out the logics that interest the organization by attending to them in a variety of ways (Bitektine & Haack, 2015; Lee & Lounsbury, 2015) and different levels of compliance (Bascle, 2016). Moreover, the chosen identity may reflect the expectations of the most powerful groups in the organization (Geng et al., 2016) or, on the other hand, the organization may seek ways to serve groups with less power and external to the organization using identities (Edman, 2016).

There is also the emergence of the vision of hybrid logic. In this case, the option to solve this situation of institutional complexity is to mix elements of several logics in order to meet the expectations of diverse institutional demands. Thus, organizations that succeed in this strategy achieve greater legitimacy and access to resources (Delbridge & Edwards, 2013), as well as being an alternative to decoupling, since it does not generate a negative feeling of not fulfilling institutional demands (Bromley & Powell, 2012; Pache & Santos, 2013).

In order to perform this process of analysis of the institutional environment, one of the assumptions of this line of thought is that actors have a higher level of agency, since actors have to align their objectives, being well aware of them, with institutional demands (Currie & Spyridonidis, 2016; McPherson and Sauder, 2013). In addition, space is opened for the micro level of analysis, identifying the decision makers and how they act in this hybridization process (Almandoz, 2014; Voronov et al., 2013).

Although it seems antagonistic to the view of competing logics, this view is complementary, in the sense of pointing to research that considers institutional logics as complementary elements. In addition, the studies should consider the actor's degree of agency and, once the agency is considered, although little considered in the cluster, it is expected that research will lead to reflexivity of structure and consequent changes in logic and institutions (Gawer & Phillips, 2013).

Finally, one of the main emerging themes in institutional theory that has great relation with the field of tourism is the cateorization and institutional change. In this case, institutional change happens through the creation, or change, of common categories through agents within the field and through consensus among them against common needs (Ansari et al., 2013). Or, institutional change can happen by changing the meaning ascribed to cultural categories, which are structures built from certain words that have a common meaning to a certain group of people (Loewenstein et al., 2012), and change the meaning of these categories. Change happens at the level of and in the institutional logics themselves (Ocasio et al., 2015).

By changing the discourse and/ or rhetoric associated with the logics and practices resulting from it, this view resumes a fundamental feature of the logics, as a provider of meaning for practices and discourses (Friedland & Alford, 1991; Thornton et al., 2012). Thus, by tinkering with the most fundamental aspects of logics, one's own logics and field change. However, in this case, there is not much agency involved and much of this transformation happens through the recurrence of practices and institutional complexity, making changes more fruitful than attending practices, than a deliberate action of the actors (Jones et al. 2012).

3 BIBLIOMETRICS

In order to demonstrate the scarce use of institutional theory in tourism research and to show how the theory is used, when it is used, we used a bibliometric analysis. Bibliometrics is a statistical analysis of academic production that aims to quantify and classify the knowledge of a given subject and is recommended to understand how it is structured (Pritchard, 1969). It is used to help in understanding the relationship between research fields, disciplines, and publications, identifying the way the area of study is structured, the main approaches used and the main works (Vogel, & Güttel, 2013, Zupic, & Čater, 2015). Bibliometrics have been used in tourism articles to research specific aspects of the field. For instance, Jiménez-Caballero and Molina (2016) studied the impact of the financial aspects associated with tourism and Sánchez, Rama and García (2016) examined the activities related to wine tourism. In this article, we used bibliometrics to investigate the influence of Institutional Theory in Tourism studies and the bibliometric technique used was the citation analysis.

Citation analysis involves counting the number of times a work is referenced in other works and was obtained with Bibexcel software (Pilkington, 2006). The underlying concept is that only articles that are related to a specific topic are cited, and therefore, the more cited, the more they influence research on the subject (Ramos-Rodrigues, & Ruiz-Navarro, 2004; Tahai, & Meyer, 1999).

Data was obtained from the Web of Science database of Thomson Reuters (www.webofknowledge.com). This basis was chosen for its comprehensiveness and for making the data available in a format that optimizes the collection and operationalization effort. Through its search tool, works that used institutional theory in tourism studies were identified through the following keywords: institutional*; Isomorphism; Decoupling. Hybridization and legitimation, in the field "topic" that does the search in the title, abstract, and keywords of the articles. The asterisk leads to the search for all the derivations of a word. No time limit was set for articles. The search focused on articles published in the main journals on tourism, considering its impact factor published by the Journal Citation Reports, in the ISI - Web of Knowledge portal (Table 1).

Table 1 Articles using institutional theory in tourism

| Impact Factor 2015 | Papers in Sample | |

|---|---|---|

| Tourism Management | 3.14 | 43 |

| Annals of Tourism Research | 2.275 | 29 |

| Journal of Sustainable Tourism | 2.48 | 28 |

| International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management | 1.775 | 12 |

| International Journal of Hospitality Management | 3.199 | 11 |

| Journal of Service Management | 2.233 | 4 |

| Journal of Travel Research | 2.905 | 2 |

| Cornell Hospitality Quarterly | 2.408 | 2 |

| Total | 131 |

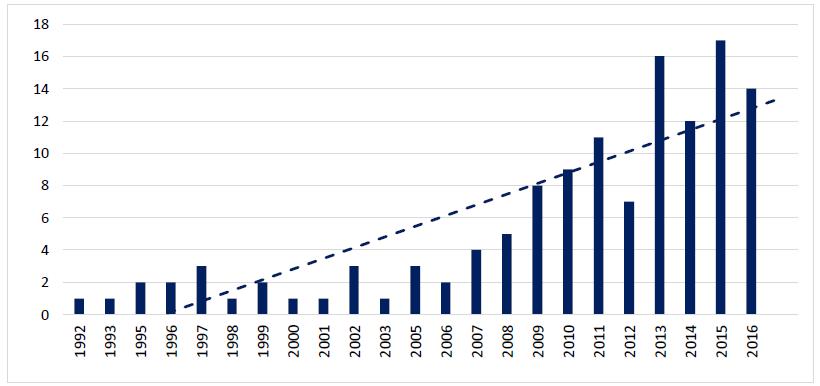

We identified 131 papers that were validated by reading their title, abstract, and introduction. Figure 1 shows the number of articles published per year of our sample. There is a growing trend in annual publications on the subject of this article (Figure 1).

The 131 articles of the sample used 8200 references. Table 2 contains the 30 most cited works. The columns show the number of citations in absolute and relative values, considering the amount of papers in the sample. For example, the article by Bramwell and Lane (2011) was the most cited among the references used in all 130 articles in the sample, was cited 14 times, in about 11% of the sample.

Table 2 Papers that have the highest number of citations from the sample

| Reference | Citations | % of sample |

|---|---|---|

| Bramwell, B., & Lane, B. (2011). Critical research on the governance of tourism and sustainability. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 19(4-5), 411-421. | 14 | 10.8 |

| Hall C, 1994, Tourism and Politics- Policy, Power and Place. New York: John Wiley. | 10 | 7.7 |

| Urry, J. (1990). The tourist gaze: Leisure and travel in contemporary studies. UK: Sage Publications Ltda. | 10 | 7.7 |

| Butler, R. (1980). The Concept of a Tourist Area Cycle of Evolution: Implications for Management of Resources. Canadian Geographer, 24(1), 5-12. | 9 | 6.9 |

| Hofstede, G., & Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture's consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions and organizations across nations. UK: Sage. | 9 | 6.9 |

| Cohen, E. (1972). Toward a sociology of international tourism. Social Research, 164-182. | 7 | 5.4 |

| DiMaggio, P., & Powell, W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Collective rationality and institutional isomorphism in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147-160. | 7 | 5.4 |

| Britton, S. (1982). The political economy of tourism in the Third World. Annals of Tourism Research, 9(3), 331-358. | 6 | 4.6 |

| Bryden, J. (1973). Tourism and development. CUP Archive. | 6 | 4.6 |

| Elliot, J. (1997) Tourism, Politics and Public Sector Management. London: Routledge. | 6 | 4.6 |

| Hall, C. (2011). A typology of governance and its implications for tourism policy analysis. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 19(4-5), 437-457. | 6 | 4.6 |

| Ostrom, E. (2015). Governing the commons. UK: Cambridge University Press. | 6 | 4.6 |

| Sheldon, P. (1990). Journal Usage in Tourism: Perceptions of Tourism Faculty. Journal of Tourism Studies, 1(1), 42-48 | 6 | 4.6 |

| Timothy, D. (1999). Participatory planning: A view of tourism in Indonesia. Annals of Tourism Research, 26(2), 371-391. | 6 | 4.6 |

| Ateljevic, I., & Doorne, S. (2000). 'Staying within the fence': Lifestyle entrepreneurship in tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 8(5), 378-392. | 5 | 3.8 |

| Bramwell, B., & Sharman, A. (1999). Collaboration in local tourism policymaking. Annals of Tourism Research, 26(2), 392-415. | 5 | 3.8 |

| Dredge, D. (2006). Policy networks and the local organization of tourism. Tourism Management, 27(2), 269-280. | 5 | 3.8 |

| Hall, C. (2005). Systems of surveillance and control: commentary on 'An analysis of institutional contributors to three major academic tourism journals: 1992-2001'. Tourism Management, 26(5), 653-656. | 5 | 3.8 |

| Hardin, G. (1968). The tragedy of the commons. Science, 162(3859), 1243-1248. | 5 | 3.8 |

| Hunter, C. (1997). Sustainable tourism as an adaptive paradigm. Annals of Tourism Research, 24(4), 850-867. | 5 | 3.8 |

| Jogaratnam, G., Chon, K., McCleary, K., Mena, M., & Yoo, J. (2005). An analysis of institutional contributors to three major academic tourism journals: 1992-2001. Tourism Management, 26(5), 641-648. | 5 | 3.8 |

| North, D. (1990). Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. UK: Cambridge University Press. | 5 | 3.8 |

| Pearce, D. (1992). Tourist Organizations. UK: Longman Group Ltd. | 5 | 3.8 |

| Pechlaner, H., Zehrer, A., Matzler, K., & Abfalter, D. (2004). A ranking of international tourism and hospitality journals. Journal of Travel Research, 42(4), 328-332. | 5 | 3.8 |

| Reed, M. (1997). Power relations and community-based tourism planning. Annals of Tourism Research, 24(3), 566-591. | 5 | 3.8 |

| Ryan, C. (2005). The ranking and rating of academics and journals in tourism research. Tourism Management, 26(5), 657-662. | 5 | 3.8 |

| Sheldon, P. (1991). An authorship analysis of tourism research. Annals of Tourism Research, 18(3), 473-484. | 5 | 3.8 |

| Tosun, C. (2000). Limits to community participation in the tourism development process in developing countries. Tourism Management, 21(6), 613-633. | 5 | 3.8 |

Source: Research data

Based on the results pointed out by bibliometrics it is possible to affirm that tourism research uses relatively little institutional theory in its scientific production. Only 131 articles published in high-impact journals in the field of tourism dealing directly with some aspect of institutional theory were found. Thus, we confirm that although tourism is a well-developed field, and institutional theory is a very popular theoretical line in other fields, the intersection of these two lines is not common and can be better explored.

There is, however, a tendency to increase the use of institutional theory in tourism in the last years of the sample, although incipient, the tourism area started to use institutional theory for some lines of research. By observing Table 2, it is possible to conclude that there are, in summary, three fields of institutional theory in tourism. The first, to discuss issues of ecotourism and sustainability, such as the article by Bramwell and Lane (2011), the most cited within the sample. This line of research deals more specifically with questions of legitimacy based on the sustainability of tourism destinations and ecotourism. A second strand apparent in Table 2 would be on social and economic issues for tourism, as for example in the articles using Hall (1994) and Cohen (1972). Finally, we see a third strand with the studies that use Hofsteade and Hofsteade (2001), which clearly denotes an analysis of culture and its effects on tourism.

3.1 Propositions

As institutional theory has yet to be largely used in tourism research, there are

some areas of tourism research wherein researchers can apply institutional theory in order to have an alternative analysis. For example, destination image might be one of the most important aspects of a destination (Chon, 1991; Govers, et al., 2007). Institutional theory can explain several aspects that compose the destination image and its consequences, such as the flow of tourists, strategies, and locals versus tourists' image.

3.2 Legitimacy

One of the central concepts in institutional theory is legitimacy. Legitimacy can be defined as "a generalized perception or assumption that the actions of an entity are desirable, proper, or appropriate within some socially constructed system of norms, values, beliefs, and definitions" (Suchman, 1995 p. 574). Legitimacy has become one of the key elements in research regarding stakeholders (Mitchell, Agle & Wood, 1997), environmental corporate responsibility (Bansal & Roth, 2002), adaptation to local institutions (Gelbuda, Meyer, & Delios, 2008; Ferreira & Serra, 2015) amongst many fields of research. In tourism, on the other hand, the element of legitimacy has attracted little attention, only coming through in research regarding ecotourism (Lawrence, Wickins & Phillips, 1997).

The pinnacle concept of legitimacy is that entities (firms, governments, destinations, organizations) are not naturally born with it. These entities must follow the trails set by older, more "legitimate" peers in order to be accepted by the public (Suchman, 1995). Legitimacy is divided into three types, pragmatic (where the entity has to act according to the expectations of their immediate public), normative (acting according to the moral standards) and cognitive (acting according to what works best and what their peers do) (Aldrich & Fiol, 1994). As entities, destinations will also have degrees of legitimacy under institutional logics that will determine how governments and businesses will compose destination image.

Destinations that have a certain image associated with them (for instance, a historical destination for cultural tourism, or a destination that has been a business center for decades for business tourism) are the ones that will set the standard for new destinations, having more legitimacy due to their traditional status. On the other hand, destinations that are striving to become cultural or business destinations will face liabilities of newness (Freeman et al., 1983). These destinations will have more difficulties in finding legitimacy then their traditional peers.

Gaining legitimacy is not an easy task, Suchman (1995) proposes that entities will pursue legitimacy by conforming to the environment, selecting their environment, and changing the environment. We propose that newer destinations will have an image strategy largely aimed at conforming to the environment, by bending to the will of their stakeholders, acting according to moral standards, and mimicking the "best practices" of established destinations. Selection of environment is unlikely for destinations, since it is not entirely possible to destinations since they cannot change completely what they are and where they are, but it is possible to select the public that best fits their infrastructure. Strategies to change the environment are also unlikely for new destinations, since the gap between tourists flow and the very legitimacy between traditional and new destinations is very large. This gap makes it almost impossible for a new destination to show the world a new "best practice" in order to change the environment. Hence, we propose:

Proposition 1: New destinations are more likely to choose strategies that promote the conformity of their image to the environment, while are less likely to choose selection and change strategies.

3.3 Isomorphism

While destinations that are already established as accepted to their specific types of tourism have an intrinsic legitimacy to their image, places that wish to become established destinations must cope with the liabilities of newness (Freeman et al., 1983). These will result in reduced legitimacy to the entities (Suchman, 1995). Hence, destinations that seek to establish themselves as valid and legitimate to certain publics will have to undertake legitimacy-seeking strategies.

One of the most common legitimacy-seeking strategies is isomorphism (Deephouse, 1996). Isomorphism is characterized by homogenization, where entities will resemble other (more legitimate) entities in their structure and actions (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983). Evidences suggest that isomorphism effectively increases legitimacy of entities (Deephouse, 1996).

There are three forms that isomorphism act. First, in mimetic isomorphism, firms, organizations, governments, and entities in general will mimic more legitimate (or successful) peers when they do not know how to act, will have to cope with laws and regulations by coercive isomorphism, and will have to adapt to industry standards and "best practices" by normative isomorphism (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983). As destinations can build their image by using marketing strategies and new destinations will be more susceptible to these institutional pressures because of legitimacy-seeking behavior (Freeman et al., 1983) there will be isomorphic pressures that make destinations position their image as resembling more legitimate peers, hence:

Proposition 2: New destinations are more likely to be affected by institutional pressures for isomorphism and will choose to mimic the image of more legitimate peers to seek legitimacy.

3.4 Hybridization

In tourism, for example, the term hybridization has been used in a more cultural context, as a form of identity formation of ex-colonies (Amoamo, 2011). On the other hand, in institutional theory, the term hybridization refers to a way of also creating identity but as an answer to a complex institutional environment. In this case, the answer does not seek to choose one institutional logic to the detriment of another, but merge several logics, granting more access to resources to organizations that choose this form of identity (Greenwood et al., 2011).

The work of Amoamo (2011) reflects a cultural face because it is a whole ethnic group, nevertheless, by adopting this hybridization of both Maori and colonizers' logics, the operators managed to overcome contradictions. Such behavior is expected in organizations that adopt the hybridization of institutional logics. As previously stated, organizations in this context are expected to achieve greater legitimacy and access to resources (Delbridge and Edwards, 2013), as well as being an alternative to decoupling, as it does not generate a negative feeling of not meeting institutional demands (Bromley & Powell, 2012; Pache & Santos, 2013).

It is important to reinforce that in the case of hybridization the actors are more aware of their actions and choices, that is, there is no pressure and an automatic response from the actor. These perceive the pressures of the environment and manage to structure a response aligned with the institutional demands (Currie & Spyridonidis, 2016; McPherson & Sauder, 2013). Based on this, and on methodological issues, this has open space for the micro level analysis, identifying the decision makers and how they act in this hybridization process (Almandoz, 2014; Voronov et al., 2013).

We can assume that many tourism organizations must reconcile global and local logics, and they must be globally recognized, but they must show the uniqueness of the sites offered (Ambrosie, 2015, Elbe & Emmoth, 2014, Kanemasu, 2013). Such a context, by itself, justifies a plural environment, composed of several logics and, as a basis for the articles cited here. It is not a good choice to privilege one to the detriment of others, all the works cited above show that hybridization, even some rather than all, contributes to the legitimization process.

Local characteristics should be maintained as a means of differentiating competitors, or, in this case, other destinations (Ambrosie, 2015; Kanemasu, 2013). In addition, if there is a loss of uniqueness of the local characteristics in this hybridization process, there is not only loss in the competitive sense, because the locality does not differ in relation to the others, but also, if local stakeholders perceived this loss, there is loss of Legitimacy vis-à-vis them (Voronov, Clercq, et al., 2013; Voronov, De Clercq, & Hinings, 2013). Based on these assumptions, we put forward the following propositions:

Proposition 3a: The destinations and organizations that adopt a hybridization strategy will have access to more resources and legitimacy vis-à-vis more stakeholders.

Proposition 3b: The destinations and organizations that lose the unique characteristics in the hybridization process will lose legitimacy compared to local stakeholders.

3.5 Categorization

Categorization can be a way of studying changes in more mature environments. That is, for instance in tourism, to "resurrect" a more outdated destination, or even a more outdated activity. In this case, institutional change can happen through changes in the meaning attributed to cultural categories, which are structures assembled from certain words that have a common meaning to a certain group of people (Loewenstein et al., 2012) and change the meaning of these categories, change happens at the level of and in the institutional logics themselves (Ocasio et al., 2015).

By changing the discourse and/or rhetoric associated with the logics and practices resulting from it, categorization takes up a fundamental feature of institutional logics as a provider of meaning and meaning to practices and discourses (Roger Friedland & Alford, 1991; Thornton et al., 2012). Thus, by tinkering with the most fundamental aspects of logics, own logics and field change are possible. However, in this case, there is little agency involved and much of this transformation happens through the recurrence of practices and institutional complexity, making changes more fruitful than attending practices than a deliberate action of the actors (Jones et al. 2012). However, such a practice may also reveal a more deliberate action by agents, bringing this movement closer to institutional entrepreneurship (Jones & Massa, 2013).

Another element associated with categorization is that it starts from the assumption that meaning in a society is socially constructed and that meaning itself is an important constituent element of society itself (Berger & Luckmann, 1966; Giddens, 2009). Thus, by changing the meaning of a category, the category itself changes. That is, mute meaning, but also the elements that will generate legitimacy, as well as the expectations of behaviors associated with that category itself. Another point that can be seen associated with categorization is the symbolic and cultural aspects associated with the category. Thus, by changing categories and the logics associated with them, the vocabulary and practices change. In doing so, the approaches of Bourdieu's concepts of habitus and symbolic capital must be observed. That is, the change does not happen only practically, but also changes, deliberately or not, the position of the actors within this institutional field (Bourdieu, 1977, 2005; Friedland, 2009). In this way, we have proposition 4:

Proposition 4: Institutional changes in tourism, when deliberate, will be associated with changes in the categories associated with the modified elements in the field.

4 DISCUSSION

In this article, we address the gap in institutional theory, i.e. its little use in tourism research. Specifically, we propose that institutional theory has several implications that can be used to analyze phenomena in tourism. Institutions shape the way a society works and virtually every human interaction (North, 1990). Hence, it is of outmost importance to understand how institutions influence destinations. In addition, part of the notion that the meanings present in society are socially constructed (Berger & Luckmann, 1966) and that these meanings guarantee legitimacy and access to resources (Roger Friedland & Alford 1991, Greenwood et al. 2008). The conformity of destinations with legitimacy pressures will shape several aspects of their image for both tourists and local community.

As destinations develop their legitimacy, they are better able to be considered by the public as valid destinations for their choice. The institutional analysis in tourism adds an important dimension for the image of a destination, as legitimacy can be one of the key elements of destination image along with natural attractions, cost, environment, nightlife, and many others (Echtner & Richie, 1991). Hence, the analysis of institutional aspects in tourism can help tourism researchers to better understand the image of a destination.

For practitioners, an institutional analysis can also help to develop the destination image for countries, cities, and regions that need to obtain or maintain legitimacy. The acts of the governments, government agencies, travel agencies, hotels and virtually every stakeholder in the tourism economy will influence the institutional environment wherein these stakeholders are included. Hence, with a better institutional analysis, the stakeholders with greater power can be able to promote changes in the institutional environment and on their destination image in order to build toward a more legitimate status.

In addition to developing the image, and even the tourism sector itself, institutional theory can contribute to understanding the changes in the sector, through concepts such as institutional logics and institutional complexity. And, from a more practical perspective, to help to profoundly modify the industry through strategies, deliberate, categorization, and hybridization.

From the point of view of the user, questions such as isomorphism may be important, as it helps not only to build legitimacy but to give meaning to destinations as social constructs. That is, new destinations that use elements of famous destinations, can facilitate the tourist in their understanding and generation of expectations. On the other hand, decoupling can help to understand the variability of experiences and ratings in websites and rankings, since destinations and elements of these have only superficially adapted to the characteristics and elements requested by websites and certification organizations.

Our article also contributes to institutional theory to the extent that this is an evolving theory, old compared to other theories, but developing further additions to answer new questions. Our main contribution is that we propose a field of study to further develop institutional theory. Tourism is a field wherein several institutional logics act simultaneously, affecting various stakeholders. Thus, it is an appropriate field to study some aspects of institutional theory, specifically, isomorphism, decoupling, concurrent logics, hybridization, and categorization.

Besides the institutional logics, the field of tourism can help to understand the studies on institutional fields, since the field in some cases can be supranational, i.e., the limits of the institutional field in tourism can be broader and have more complex and diffuse limits than in management studies. In addition, tourism can offer elements to go beyond a new "new" institutional theory by relating more complex themes, even within an institutional field, by relating Bourdian elements such as symbolic and cultural capitals (Bourdieu, 2005, 2006; Friedland, 2009). For international tourism is increasingly present for less privileged portions of the population or even less open to tourism are embracing this practice. Thus, both the transfer of capital and the space occupied by them in their fields are changing along with the field.

Nevertheless, institutional theory is always evolving and has presented itself under many forms (institutional economics, new institutional economics, new institutional theory, neo-institutional theory, etc.). Hence, it is notable that institutional theory is a theory that changes. It has evolved from a more economic basis into a very sociological basis over the last years. These developments are important for future studies in tourism, since the evolution of institutional theory will provide new lenses that can be used to understand phenomena.

5 FUTURE RESEARCH

Future research in tourism can capture the basic concepts of institutional theory and use it to analyze objectives in tourism. Institutional theory can be of use in tourism by analyzing much more than destinations and stakeholders. Economic, sociological, and political settings that touch tourism in some way can also be analyzed using institutional analyses. In this paper, we build three future research agendas in this sense.

First, researchers can use institutional theory concepts to analyze how government and tourism agencies of governments decide how to invest in destinations. Countries can have multiple destinations that can have different characteristics and different types of tourism involved. However, governments have to invest in these destinations to, for instance, promote their image or building infrastructure. Institutional aspects can determine where governments will spend their funds investing in tourism by analyzing how destination legitimacy plays a role in government expenditure in destinations. This research could contribute to governments by explaining some of the decisions they make, as well as to institutional theory by building a bridge between legitimacy and government investment.

Second, the use of isomorphism as a basis of analysis. As all organizations, destinations, governments, and other entities suffer pressures from the environment, there will always be some level of isomorphism in their structure, shape, and actions. The use of isomorphism as a basis of analysis that can help tourism researchers to better analyze destination image, more specifically, the image that a destination intends to build using its communication and marketing strategies. This image will be highly influenced by the environment, as peers that are more legitimate will influence entities to adopt similar behavior and form. The analysis of form that entities build for themselves is important because it has implications for several publics, such as tourists, governments, firms, and the local population.

Future studies can also use institutional logics and the movements of hybridization and categorization to analyze how institutions will shape the destination and its relations with the environment. As there are several logics working in tourism, discourses will have to be hybridized between these logics or categorized into new meanings in order to promote the balance between logics. These movements will determine not only destination image, but also the acceptance of this image between the many stakeholders, its legitimacy between these stakeholders and these factors may have great impact on the economy of destinations as more legitimate destinations will have an advantage against less legitimate peers.

6 CONCLUSION

Although institutional theory is a developed and widely accepted theory, there is significant space for new research of its use in other in several areas of research. In tourism, for instance, we see a strong area that has scarcely resorted to institutional theory for analysis. The combination of tourism and institutional theory can bring strong contributions for both lines. We hence call for the attention of researchers in tourism to resort more to institutional theory on their analysis, as well as we call for the attention of institutionalists to resort to the tourism area as an important object to test and develop new theory in the future.

texto em

texto em