1 INTRODUCTION AND OBJECTIVES

This study explores the relationship between two different, yet complementary concepts: monasteries viewed as sacred spaces, and monasteries in relation to landscape and tourism.

The main aim of the study is to analyse how monasteries and their gastronomy interact with tourism, i.e. how tourism related to the traditional food produced in monasteries can help diversify the tourist product in these places, attract more visitors, improve visitor's satisfaction, and increase revenue in order to upkeep the place.

Secondary aims are as follows:

-To explore the relationship between the tangible (built space) and intangible (traditions, customs, rituals, including food) heritage atributes of monasteries, thus emphasizing the relationship between the monasteries and their local cultural landscape.

-To identify the impacts of tourism on these spaces, taking into account that they are not only heritage sites, but also sacred places that have to be respected.

After reviewing the academic literature on this topic, the article is structured in three sections. The first defines the concept of monastery as a sacred space, based on both classical and contemporary works on the history of monasteries and of the sacred. The second identifies the opportunities and challenges of sacred places, particularly monasteries, when they become tourist attractions. The third and final part analyzes how gastronomy, particularly wine production, can improve the visitor's experience in these spaces. Some good-practice cases of Spanish monasteries that are already employing this strategy are illustrated.

2 MONASTERIES AS HOLY PLACES

Medieval monasteries would feed off the land surrounding them, the habits and routines established within the monastic community transformed crops and land in function of their needs, and this partly explains the development of vineyards in many medieval monasteries. Today these resources, both tangible (buildings) and intangible (traditions, gastronomy etc.), are valued by the tourism sector.

Cultural traditions recognize the sacredness of these places, and religious traditions nurture and adapt them, projecting them into the world.

We refer to tangible sacred spaces as those constructed with a particular harmony and order, connecting with the transcendental harmony and order. Those who wish to reach perfection inhabit them, both physically and spiritually. They are physical spaces, which the human community has given a special reverence to, in order to aid communication between man and the divine.

There are many examples of hermit architecture around the world. In Middle Eastern and Western traditions, the symbolic representation of the sacred space materializes in different ways, one of which is the monastery. In the oriental monastery, hermit-like dimensions prevail, whereas the Western monastery has coenobitic dimensions.

Monks or nuns inhabit monasteries, working together, sharing prayers, and day-to-day life. Monasteries are usually found outside of cities, in places that favor a life of prayer and reflection, although nowadays they can also be found in large urban areas (UNESCO Association for Interreligious Dialogue, 2015).

Monasteries spread throughout Europe during the Middle Ages but, as Moreno (2011) points out, they were originally a reaction from the first hermits to the luxury and splendour displayed by the Church. In fact, the word monastery comes from Greek, and means "house of a single person". Initially, they were inhabited by a single monk (or hermit), who retired to a remote area to devote himself to prayer and penance.

It was Saint Pacomi (286-346) who first proposed the shared hermit life, and organized coenobitic monasticism under his rule (Estradé, 1998). Later, Benedict of Nursia (480-547) organized the first medieval monasteries and founded the Benedictine order (Rule of Saint Benedict), one of the most prominent religious orders during the early centuries of the Middle Ages. In fact, the Rule of Saint Benedict served as a model for other monastic rules. It is noted for its balance, practicality and being based on poverty, chastity, obedience, prayer and work.

The medieval monastery was designed as a space to serve God and had several parts. The cloister was a space for silence, distribution, water collection, and light. Symbolically, it was the beating heart in the body of the monastery. The chapterhouse was the quality control center of the spiritual life. The church was a place of cultural celebration where daily prayers took place; it was also a center for architecture, symbolizing the cross, and open to the public. The library was a place of learning and wisdom, and the scriptorium was where sacred texts were copied. There was a common dormitory, a refectory, where meals were served, and a cellar, where food and drinks were conserved along with medicines and other basic essentials. Sometimes, also attached to the monastery, you could find a palace or the abbot's residence, the town or village walls, a nice house or even a village.

The monastery was an ideal community with a closed system. Benedict of Nursia, coenobites and the monastery coincided in the region of Subiaco, Italy. Monte Cassino, in Lazio, was the first great Benedictine monastery, and a model that would continue evolving until the emergence of Cluny.

The monastery, as a receptacle and model of how to live, experienced considerable crisis in the 8th and 9th centuries. However, around the year 1000, the monastic model introduced after Cluny mushroomed in countries that are now France, Germany, England, Italy, and Spain. The Cistercian order moved towards cleaning up and dismantling the non-essential elements of the monastery. The Civitate Dei (City of God) wanted to restore simplicity, going back to the essential.

Today, UNESCO, through its World Heritage sites, has singled out the value of monastic architecture and way of life, and has highlighted how this living habitat has been a civilizing model, in lifestyle, organization, and function. Monasteries in Armenia, Bulgaria, Georgia, Germany, Greece, Mexico, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Serbia, and Spain have been granted World Heritage status.

Attention has also been drawn to gastronomy as a heritage resource. The European culinary culture, both meal preparation and table manners, originated in medieval monasteries and abbeys. Monasteries served a double function: they provided hospitality and accommodation to travellers and hospitals to tend the sick. They upheld the idea of consuming minimal food in their quest for spiritual fulfillment, in contrast to the Barbarian cultural model. This concept of essential food grew in parallel to essential architecture and monastic liturgy. Food was part of a liturgical act, aspiring to a sacred experience. In the medieval period, nuns usually ate twice a day, except Wednesdays and Fridays, when they only ate once. They fasted during Lent, the second half of September (digiurno regularis) and Advent. However, they ate larger quantities and wider variety of food at Christmas, Easter, and Pentecost. The monastery brought together production, a way of life, knowledge, food, liturgy, and intense spiritual aspiration, and therefore was the place where experience and learning sat side by side.

Thus, the monastery is not only an architectural space but also a space for finding community life and searching for God through certain religious practices (prayer and worship), and this is why they are, primarily, holy places.

The holy is a complex concept that can be defined and/or studied from different perspectives. In this respect, Aulet (2012) mentions the following:

-The holy is all that is irrational and marked by some form of transcendence.

-The holy as a designation of divinity, fundamental reality, pure existence; which in some cases means it is also associated with terms related to clarity, light, or purity.

-The holy is spiritual and pure, and therefore separate from the profane. In contrast to the profane, it involves delimiting inappropriate behaviors and conducts. This is the holy of prohibition and separation.

-The holy as something that brings us closer to divinity; that which can be understood as a holy consecration.

-The holy is the root of a spiritual life; marked by fascination and internal development, leading to fulfillment.

The holy is present in all religious traditions as something that brings us closer to divinity, and is shown as its manifestation (hierophany). We can conclude that the holy is defined by its opposition to the profane (Eliade, 1981; Durkheim, 1993), and is ontologically different to it; there is nothing human or physical about it, rather it always manifests itself as a reality of a completely different order to that of natural realities. It is what Otto (1965) calls ganz andere. Holy and profane represent two different ways of being in the world.

"The holy equates to power itself, in short, to reality par excellence. The holy is saturated with being. Holy power means reality, perpetuity and efficiency" (Eliade, 1981, p. 20).

The holy fact appears as a stable or ephemeral property of certain things (objects of worship), certain real human beings (priests), imagined beings (gods, spirits), certain animals (sacred cows), certain places (temples, sacred places), certain periods or times of the year (Easter, Ramadan). It is a superior quality, which opposes chaos.

In the case of monasteries, these can be considered holy spaces for various reasons, as noted by Aulet & Hakobyan (2011).

- Firstly, they are holy spaces because they share the symbolism of the center of the world: the point of convergence, coordination and ordering, balance and harmony.

- They are places where there has been a manifestation of the holy (hierophany). This can occur in various ways, but is often linked to elements of nature which are holy in character (water, stone, forests), as well as those natural areas unreachable by man and which somehow convey that feeling of smallness of the human being, mentioned by Otto (1965). "All religions, as cultural phenomena, have used natural symbols to come closer to the mystery of the world" (Duch, 1978, p. 343).

- Finally, there is a whole range of architectural symbols. From an architectural perspective, religious buildings, especially temples, are the physical place where the holy space materializes. Therefore, their architecture is anything but random. Each part symbolizes or shares one of the symbols representing the holy. This is discussed at length in the literature (Guénon, 1995; Burckhardt, 2000; Hani & Quingles, 1996; among others).

3 SACRED SPACES AND TOURISM

The relationship between tourism and religion is getting closer, and the conceptual barriers are increasingly diffused. The most visible connection between tourism and religion are the scores of sacred buildings that attract tourists. This increasing interest is largely due to the buildings' cultural and historic value, rather than their religious function.

After carrying out a complex study of pilgrimages in Western Europe, Mary Lee and Sidney Nolan published the most acknowledged classification of religious tourist attractions (Nolan & Nolan, 1989).

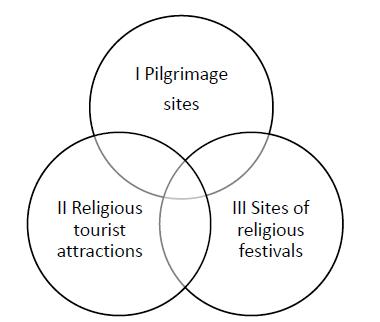

As shown in Figure 1, Nolan and Nolan (1989) propose a classification of religious tourism resources based on three overlapping typologies: pilgrimage sites (I), religious tourist attractions (II), and sites of religious festivals (III). Pilgrimage sites and religious tourist attractions differ in that the first are visited by pilgrims and have little tourist value, while the second are visited just as much by tourists as they are by religious devotees. They are not, however, considered as pilgrimage sites, and it is in this group that Nolan and Nolan place monasteries and cathedrals.

In the overlap between pilgrimage sites (I) and religious tourist attractions (II) we find what we will call group I (b): sites of pilgrimage with a high value as tourist attractions. These sites are famous for their art, architecture and/or particular characteristics and tourists can easily outnumber pilgrims here.

The third group (III) includes sites of religious festivals, where important religious events, such as Holy Week parades and Corpus Christi, or Christmas and Easter are celebrated. This group is also linked to pilgrimage sites, forming group I (c): pilgrimage sites where important religious events take place.

It is logical to arrive at the conclusion that a religious temple can be (or not be) a tourist attraction depending on its artistic, historic and architectural value. This is quite clear in Europe, where there are a relatively large number of local and regional sites that only attract the attention of a few tourists, given that they have relatively little artistic or architectural value. However, they do attract a large number of devotees from the local or regional area.

Therefore, despite the fact that the original function of the majority of sacred places is linked to religion, as in the case of monasteries, we can add that they also fulfill another function related to tourism.

Table 1 Classification of religious heritage in tourism

| Movable Heritage | Immovable Heritage | |

| Religious function | Liturgical objects used in Mass | Sacred spaces and sites in use (property of religious communities) |

| Tourism/cultural function | Liturgical objects in disuse, displayed in museums | Sacred spaces in disuse - monuments (not usually belonging to religious communities) Ancillary buildings belonging to religious communities |

Source: Aulet (2012)

There is a fundamental distinction between movable and immovable religious heritage. Movable sacred objects are significant for tourist-visitors, but essentially for their historic and cultural value, and any religious value is given little importance. In contrast, immovable religious heritage has two functions: the first is its original purpose, as a building in which believers can worship; the second is its historical, cultural and artistic value, which both religious and non-religious tourists can admire, just as they would a museum. This second function is pagan, and practically eclipses its religious function, given that any religious function is restricted to a very specific segment of the tourism demand. Sacred buildings that have a special interest from this perspective have practically lost their religious function.

Within this second function, we can also find a group of religious items, which includes numerous religious buildings, which are also used by believers. These buildings are used to offer tourist services (regardless of the motivation) and include monasteries, convents, seminaries, religious schools, etc.

Broadly speaking, there are two possible positions that a visitor can take when in the presence of a sacred monument: to worship, in the original, religious sense of the word, or worship of the physical monument as a representation of the collective memory of the community. Managers of the most visited religious buildings (including monasteries where there are religious communities) have an increasing understanding that the needs and expectations of tourists are different from those of pilgrims.

MacCannell (1976) defines the continuity of the roles of pilgrim and tourist by introducing the concept of authenticity, which is the modern equivalent of the traditional sacred experience. MacCannell affirms that the tourist is looking for authentic experiences, and therefore defines the tourist as a secular pilgrim who wants to give meaning to their life through experiences they can have away from home.

According to Cohen (1979, p. 27-28), we can distinguish four types of tourist situations:

1. . Authentic situations. This is a real situation, recognized as such by tourists, and occurs outside tourist areas.

2. . Organized authentic situations. As described by MacCannell, where the tourist establishment stages the scene for the tourist, but the tourist does not know this and thinks it is real and authentic. The organization presents its artefacts as real and deliberately keeps the tourist unaware of the fact that it is staged. Cohen calls this "a concealed tourist space".

3. . Non-authentic situations. In this situation, the staging is objectively real, but previous experiences, where situations that appeared to be authentic were not, have taught the tourist that they were deliberately deceived. They are therefore doubtful of the authenticity and think they are being manipulated, but in fact, this is not the case.

4. . Artificial situations. In this situation, the hosts organize the staging, and the tourist is fully aware of this. Cohen calls this "an open tourist space". A good example is a tourist space where specially designed villages depict traditional lifestyles of the past - representing communities which have disappeared or been changed. Another example is representations of traditional dances and rituals, which are put on expressly for tourists in places and at times which are most certainly not the original ones.

A non-authentic attitude towards a place is essentially not giving the place meaning. This implies not being aware of the deep and symbolic meaning of the place and not appreciating its identity. This non-authentic attitude is transmitted through a number of processes, or means, which directly or indirectly favour the anonymity of the place, and which, supposedly, weakens its identity (Cresswell, 2005).

This discourse coincides with the tourism discourse on authenticity in religious places. "Tourists, every bit as much as devotees, have a keen interest in an authentic experience of the place"(Bremer, 2006, p. 32).

When tourism and sacred spaces come together, it is important that these places do not lose their identity and reason to be.

The cathedral as heritage tourism attraction is also sacred space, identified as such by the majority of its visitors even if they do not know the correct means of behaviour and are unable to articulate the significance of its seeming immutability as a component of their experience. It becomes important that the cathedral appears to be untouched by the modern world, even if in practical terms this is romantic, but impossible, as the building has been continually modified since its construction. The tourist, however, sees it as a space to be preserved rather than used, to be gazed upon but not changed (Shackley, 2002, p. 350).

Introducing tourism to these spaces can generate changes in their spatial and environmental reality, and leave a mark on the cultural traits that characterize them. Tourism implies consumption, and places have to adapt to tourism through intermediaries, interpretation, representation, and transformation. Tourist spaces have to be both symbolically recognizable and maintain the balance between safety and comfort, and unknown and surprising. This is why it requires appropriate forms and contents (Anton Clavé, Gonzàlez Reverté, & Fernández Tabales, 2009).

The religious understanding of a place creates spaces different to those from tourism perspective. This duplicity offers an abundance of opportunities to converge and overlap: what is sacred for devotees and the aesthetic and commodified for tourists.

Tourism development also creates new tensions, between the use of sites as tourist destinations and the maintenance of "sacralised" notions of place. There is a serious risk that some monasteries may find themselves "invaded" by increasing numbers of tourists. Songtseling, for example, receives a large number of tour groups every year and the sale of tickets to tourists is currently a key income source for the monastery, as well as a source of revenue for the country's government. Economic concerns have led to a situation where tour groups and their guides are admitted to the monastery from morning to evening, regardless of what rituals are being performed. The presence of tour groups and their guides wandering around the premises may sometimes be distributing. The monastery has issued complaints to the local government about this, but the problem is currently far from being solved (Kolås, 2004, p. 274-274).

For this very reason, several countries have adopted policies to avoid tourism. For example, the Kingdom of Bhutan, in the Himalayas, has prohibited foreigners from entering certain places in order to preserve its culture. This country has decided that the income generated by tourism does not compensate the problems it creates, which has included the theft of relics, desecration, the looting of monasteries, and the corruption of the local population (Hough, 1990).

Even though devotees and tourists occupy the same place at the same time, their practices are different realities. In this way, sacred spaces maintain what Bremen (2006) calls simultaneity of space. An individual's experience can be a cross between religion and tourism, when tourists participate in religious activities and when the practices of religious followers become an attraction for the tourists.

The types of tourism linked to sacred spaces and religion represent, from a tourism point of view, a search for the authentic and a sacred experience. We are dealing with a tourism with spiritual connotations, which alleviates the volatility and apparent meaninglessness of everyday life (Gil de Arriba, 2006).

When we talk about sacred spaces and tourism, different typologies coexist. Not only religious tourism exists in sacred spaces, but also cultural, spiritual, or even food tourism.

Today religious communities are aware that tourism is a source of income that helps finance the community, and some have incorporated it into their daily practice with visits, stays, and even the sale of products that they have traditionally produced.

4 THE LANDSCAPE OF MONASTERIES, THE LANDSCAPE OF GOOD TASTE

Tourists with differing motivations and needs can be challenging at times, when it comes to managing the religious, cultural, and tourism aspects of a monastery. Our focus shifts to the value of the monastic heritage, and to those interested in art, culture, and gastronomy.

Monasteries can be seen as an exponent of the concept of holy space, and are closely related to the landscape where they are located. They are an example of how tangible and intangible heritage are interrelated: buildings respond to specific needs related to the daily routine of the community (including religious needs) but with symbolic meanings. According to Shackley (2001), holy spaces are linked to different religious traditions, but they all share some of the characteristics mentioned above. At the same time, they are spaces containing a set of values (related to worship, nature, culture, and architecture, among others) that make them highly attractive. In most cases, in the eyes of tourists, they generate a flow of visitors alongside the faithful and devotees who come to these places for religious reasons.

The 1982 World Conference on Cultural Policies, organized in Mexico by UNESCO, defined the cultural heritage of a people as that which.

Includes the works of its artists, architects, musicians, writers and scientists and also the work of anonymous artists, expressions of the people's spirituality, and the body of values which give meaning to life. It includes both tangible and intangible works through which the creativity of that people finds expression: languages, rites, beliefs, historic places and monuments, literature, works of art, archives and libraries (UNESCO, 1982).

We understand tangible religious heritage to consist of both tangible and intangible elements. This tangible heritage represents, in some way, the holy space. It also includes tangible heritage objects, such as paintings, altarpieces, decoration, and items of liturgy considered works of art. Thus, we can understand that tangible heritage represents an interest in art, architecture, and history in general; and we can link it to motivations that are largely, but not exclusively, secular (we can call this cultural tourism, for example). In this regard, the majority of European monasteries were built in the Middle Ages, becoming magnificent representations of different artistic styles (such as the Romanesque and Gothic).

On the other hand, intangible religious heritage is made up of the rituals, worship, and events that take place in these holy spaces. We could say that this type of heritage is a clear manifestation of sacred time, meaning people's devotion towards a particular element, and the rituals of integration that occur in these places. Therefore, we could associate these elements with more strictly religious motivations.

We could even go a little further.

Bearing in mind that, as already mentioned, these monasteries also have a close relationship with elements related to nature and the territories surrounding them, they can even be considered part of what UNESCO calls the cultural landscape.

During the Middle Ages monasteries came to be considered not only as centers of spirituality and a source of culture, but also as organizers of the country. The close relationship that existed between the monastic communities and feudal authorities is a clear reflection of this. Monasteries played an important role in the economy of the surrounding areas, often owning farmland and herds of cattle, which the monks themselves looked after (remember the main premise of the Rule of Saint Benedict, "ora et labora"), while also providing employment for local peasants.

In the relationship between tangible and intangible heritage and landscape, gastronomy is a clear example of how these relate to one another. According to the Institute of Catalan Studies, "gastronomy is the knowledge of everything related to cooking, processing, and preparing dishes, the art of tasting and appreciating food and beverages". Montecinos (2012) adds that "gastronomy is the reasonable art of producing, creating, transforming, develop-ping, preserving and safeguarding activities, consuming healthily and sustainably, enjo-ying natural, cultural, intangible, and mixed World Gastronomic Heritage, and all in respect of the human food system".

We therefore find that gastronomy constitutes the relationship between food and culture, and takes in all of the culinary processes and traditions of each region. We have seen the definition of intangible heritage and its relationship with monasteries; this is also evident in the case of gastronomy. As an example, we can cite the inclusion of French cuisine on UNESCO's list of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity (2010), followed by the Mediterranean diet and traditional Mexican cuisine. There are several monastic texts on food, rations, expenses, etc. written by monks and nuns, indicating ingredients, dishes suitable for days of the year and religious festivals. The earliest of these preserved manuscripts date back to the fourteenth century.

The importance of the culinary legacy of monasteries is further endorsed by the facilities themselves. The architectural design especially that of Benedictine monasteries, was clearly in response to culinary needs. Life in the monastery was structured around the church and the cloister, the most important places around which the other areas were built.

The cloister tended to be square or trapezoid in shape, each of its sides covered by a gallery with an archway. At the centre of this space, there was usually a small garden or a vegetable plot (where they planted herbs). Frugal meals were served in the refectory, usually around noon. While the monks ate, one of them read the Scriptures from a pulpit. "Reading will always accom-pany the meals of the brothers. Let there be complete silence, and no voice other than that of the person reading may be heard. Everything needed to eat and drink is to be served by the brothers to one another, in order that no one need ask for anything. If anything is required, this is to be done by making a sign rather than speech" (Rule of Saint Benedict, Chapter 38; Just, 2007).

The kitchen was next to the refectory, and close to that, the store and warehouse. Land surrounded this ensemble (the amount of land was in accordance with the monastery's importance), as well as other buildings such as mills, workshops and stables. The winery was a very important building, and monasteries played a crucial role in preserving the culture of wine. In fact, with the risk of this culture disappearing following the Islamic invasion, monasteries were responsible for continuing to plant vines and produce wine for liturgical reasons.

Farms related to the monasteries kept livestock in a planned, rational, and independent way. The farm was no more than one day away from the monastery, so Mass could be attended on Sundays, and was normally worked by converts (those who professed to the order but had not joined, or were unable to). One of the important functions of the farm was to meet the needs of the community regarding food, and it grew all types of crops, in addition to producing wine and savory meats. The most common crops were cereals (wheat, barley, and oats), olives, grapes, vegetables, fruit, and herbs for cooking. Livestock was important and included pigs, sheep, and goats. Poultry, if there was any, was reserved for special occasions. Firewood was also gathered from the forest. Each monastery enjoyed complete economic independence, although they did exchange plants, seeds, and mushrooms, among other things, with one another.

Thus, the culinary tradition of monasteries stems from a combination of observing the monastic rule and eating the products that were most accessible. The monks' diet was made up of vegetables, fruit, eggs, fresh and salted fish and cheese. At ceremonies, they were allowed biscuits and nougat. Fish was much more frequent than meat or meat products. Although monastic rule prohibited red meat, it said nothing about poultry. "Therefore let two cooked dishes suffice for all the brethren; and if any fruit or fresh vegetables are available, let a third dish be added. Let a good pound weight of bread suffice for the day, whether there be only one meal or both dinner and supper. Except the sick who are very weak, let all abstain entirely from eating the flesh of four-footed animals." (Rule of Saint Benedict, Chapter 39; Just, 2007).

There was also a tradition for nuns to make jam and sweets, normally to use up any surplus fruit and vegetables, or as gifts for benefactors and relatives. Today, many of these products are still the main source of funding for those monasteries endeavoring to attract commerce.

Monasteries have also traditionally played an important role in the production of wine in Spain and many other parts of Europe. With the fall of the Roman Empire, Christian monasteries became wine centres throughout the Middle Ages. Wine was also a key item in the liturgy, in addition to being a commodity that could be exchanged.

Wine and vineyards form part of the cultural heritage of a region. They are essential to the understanding of the economic, social, and cultural evolution of different wine-producing regions, and also help forge a European cultural identity. It also conveys loyalty to origins and learning to enjoy local products related to the land. As Josep Roca, the sommelier at Celler de Can Roca, has pointed out, behind every wine there is a philosophy that speaks of the land and of the people who produced it.

Winemaking came from the ancient Greek and Roman civilizations, crossing the Mediterranean to Spain, and has been part of Spanish history, heritage and cuisine ever since. The Spanish landscape cannot be explained without wine, or monasteries. Despite the fact that numerous monasteries in the Middle Ages produced wine, today there are practically none. Many have handed their vineyards, and even their name, over to wine businesses, but the monks no longer work the land or make wine. However, various monasteries have taken advantage of the fact that it has become a tourist attraction, and have organized visits to the vineyards, or prompted by tourist organizations, offer tourist packages that include visits to monasteries and their wineries.

One of the last monasteries still producing its own wine today is the Cistercian abbey of Santa Maria de la Oliva, in Carcastillo, Navarra, in the north of Spain. The monks here make wine from 20 hectares of vineyards, and have upheld the craft for 900 years. The winery can hold up to 400,000 litres, and today around 150,000 liters of wine is produced every year. The commercial name of the wine is that of the abbey "Monasterio de La Oliva", and belongs to the Navarra Denominació d'Origen (DO), a regulatory classification system for Spanish wines and foods according to Agricultural European Rules (Turismo de Navarra, n.d.).

The monastery and winery is open to visitors, and being a Cistercian monastery, it offers lodgings to those who are looking for a few days' silent retreat, peace, prayer, and refection. The rooms are in a restored 18th century building, which can accommodate up to 15 guests. Visitors are welcome to partake in prayers if they wish, and spiritual accompaniment is offered on request.

Monestir de San Pedro de Cardeña de Burgos (Castilla y León) is another monastery that makes wine. This Trappist abbey makes Valdevegón wines, following traditional artisanship. The wine is stored in the 11th century Romanesque cellars, where the naturally stable temperature and humidity ages red wines such as Ribera de Duero or Rioja. This monastery also offers visits and lodgings with the community, as well as producing beer, chocolate, and sweets, which can also be bought online (Monasterio de San Pedro de Cardeña, n.d.).

Scala Dei is one example of a monastery that made its own wine in the past, but the production has now been taken over by a wine business. This Carthusian monastery was founded at the end of the 12th century in Tarragona (Catalonia), in the east of Spain. Like other monastic communities, it acquired the land around the monastery, and planted vines to produce wine. It was abandoned in the 19th century, as were other monasteries, due to the ecclesiastical confiscations of Mendizábal, and fell into the hands of five families who founded a private society. The society promoted the cultivation of vines for wine, and was one of the advocates of DO Priorat. This is how Cellars d'Scala Dei began, and today it still produces wine under the name of the monastery.

Despite the wine being well known, the monastery fell into serious disrepair. Finally in 1991, it was handed over to the Catalan government, who have since restored the building and opened it to visitors (Cellers d'Scala Dei, n.d.).

Numerous monasteries have been incorporated into wine routes, the most iconic of which is, perhaps, La Rioja. La Rioja is the oldest DO in Spain, and its long tradition of producing high quality wines has won it a place amongst the most renowned in the world. Today, its wines are recognized for their exceptionally high quality and authenticity.

Rioja was one of the first DO's to adopt the concept of wine tourism, and to be incorporated into Spanish Wine Routes. One of the tourism products it offers is a combined visit to the monastery and cellars, where a full day visit (from 10.00 a.m. to 3.00 p.m.) costs 14 euros, and includes wine tasting. Proposed visits include the San Millán de la Cogolla monasteries at Suso and Yuso (World Heritage Sites), Bodegas Ontañón de Logroño, or Bodega Finca Valpiedra in Fuenmayor (Rutas del Vino Rioja, 2014).

Another example of a tourism product is Spanish Paradores, a hotel chain conceived in 1910 by the Spanish government with the intention of improving Spain's image abroad. Following on from this, Alfonso XIII of Spain undertook selecting the spot for the first Parador in Sierra de Gredos, between Madrid and Ávila, in 1926. After the Parador was opened in 1928, the Committee for Paradores was formed, and began to look for unique buildings with a long cultural history for future hotels. One of the aims of the project was to preserve the country's heritage, and this is why many of them are castles or monasteries. Apart from accommodation, they offer other tourism products such as visits to monasteries and wine routes. There are three distinct wine routes: Rioja and Navarra; Ribera del Duero; and the wines of Rueda and Toro (Paradores de Turismo de España SA, n.d.).

The Tourist board in Galicia offers several products, for example the Ribera Sacra tourist train. This is a train ride which combines a visit to a winery with an interpretation center and a visit to the monastery of Santo Estevo de Ribas de Sil (Avista Ribeira Sacra, 2011). It is evident that there are a considerable number of tourism initiatives linking wine to monasteries. There are, also, other initiatives to the valorization of monasteries, and many of them now offer visitors accommodation, guided tours and a shop to buy their produce.

One such example is "Spiritual Mallorca", which offers a joint ticket to various monasteries on the island. Mallorca is well known for its sun and beach tourism, but Spiritual Mallorca presents a different Mallorca; a Mallorca full of heritage, culture, emotions and soul. "Our privileged setting and climate have turned our island into a first-class tourism destination, but Mallorca offers so much more than just our beloved sun and magnificent beaches. This place, at the crossroads of the Mediterranean, has an extraordinary history, world renowned figures, and a wealth of natural and cultural heritage..." The joint ticket includes six religious sites on the island (Lluc Sanctury, Cura Sanctuary, La Porciúncula, Real Monastery, Saint Francis Convent and Sant Juníper Serra Museum/home). Apart from the visit, it also offers discounts, guided tours, venues for events, and also acts as a promotional platform and source of tourist information (Lucus Gestió d'Espais i Natura, n.d.).

The 12th century Monastery of Avellanes is an example of a monastery well prepared for visitors. Apart from accommodation, it has developed a whole range of tourism products to attract tourists and now promotes local products such as wine and olive oil. Once a seminary, today the abbey is used for tourism, offering monastic accommodation (37 rooms), a restaurant (open daily offering local food), Montsec Conference Centre (with various meeting rooms), a Spiritual Center, a shop (selling local products), summer camp accommodation, and a library and archive center. This is in addition to various other activities such as guided tours, exhibitions, concerts etc. (Monestir de les Avellanes, n.d.).

Regarding local products, monasteries not only produced wine, but also other products such as olive oil. The oil was used in liturgy, in medicines and lighting. Other products such as sweets or chocolate were exchanged for goods or given as presents to visiting pilgrims.

Cocoa came to Europe via Spain, and was introduced almost simultaneously with other exotic drinks such as coffee and tea. Bufias (2015) relates the story of Cortès being presented with a golden goblet of liquid cocoa by the Indians because his physical features resembled those of their god.

The next country to adopt chocolate after Spain was Italy. Some Italian regions were under Spanish rule and brought chocolate from the Iberian Peninsula, thereby beginning its tour of Europe. Although the drink had a strong, bitter taste, it was imported to the Peninsula, as it was easy to transport in grain form (it could not be cultivated in Europe). It was brought to Europe from Spain through the monasteries and royal courts. France was the third European country to embrace chocolate, and it rapidly spread through the French aristocracy.

It was Cortès who brought cocoa to the Peninsula, giving Friar Jeroni d'Aguilar a sack of cocoa beans to take to the port of Barcelona, together with the recipe for chocolate. From there the cocoa travelled to the abbot of Pedra monastery in Aragon. Bufías (2015) explains that it was in this monastery that the first chocolate was made in 1534, thus linking the chocolate-making tradition to the Cistercian order, particularly its reformist branch, the Trappist.

The production and consumption of chocolate in monasteries is well documented throughout history. Seventeenth-century chocolate, being liquid, did not violate the rules of ecclesiastical fasting: Liquidum non frangit jejunum, and this meant it could be drunk without sinning. After its spread throughout Europe, theological doubts arose in Catholic countries (Spain, Italy, and France) as to whether consuming chocolate broke the rule of fasting. The issue began in the early sixteenth century in Spain, and the debate gradually grew until it reached a papal level, and the Pope being asked for a resolution on the matter.

At Pedra monastery in Aragon, in addition to guided tours, visitors can also see an exhibition on the history of chocolate (Monasterio de Piedra, n.d.). In parallel to this, the tourism authorities in the city of Zaragoza have created a tourist product based on chocolate, called Chocopass. The pass can be used to sample five different chocolate specialties from more than 20 outlets, plus a tasting session at Pedra monastery (Ayuntamiento de Zaragoza, n.d.).

5 REFLECTIONS / CONCLUSIONS

As we have seen, the relationship between heritage (both tangible and intangible), territory, and gastronomy constitutes an opportunity for regions to develop tourism around monasteries and to gain extra income to help with the upkeep of these infrastructures.

Thus, cultural tourism and gastronomic tourism can bring significant benefits to regions where it is implemented, if properly planned. It can benefit small food producers and artisans, and lead to the recovery (or prevent the loss of) ancient crafts, traditions, recipes and products. In this sense, the tendency to award new value to local produce throughout a district is key.

We can see that the diversity of visitors in these places hampers their management and tourism promotion. "Many people travel to a widening variety of sacred sites not only for religious or spiritual purposes or to have an experience with the sacred in the traditional sense, but also because they are marked and marketed as heritage or cultural attractions to be consumed" (Olsen, 2006, p. 5).

Even though pilgrimage sites have always been linked to commercial activities involving transport, accommodation, food and the sale of religious items, what is new is that the site is now selling itself as a tourism destination, with heritage being the main tourist attraction.

Monasteries can pass, thus, from the religious tourist to the food tourist, or the spiritual tourist. However, the cultural and heritage resources alone cannot be converted into cultural tourism, and therefore, tourist services need to be provided. Sacred spaces inspire reverence and penitence. In contrast, the profane is ordinary, mundane and without any religious meaning. Therefore, managers have to think carefully about what type of service and infrastructure they want to offer, so as not to cause a clash of interests.

Attention should be paid to what some authors call commodification, and be careful that over commercialization of products associated with sacred places (legends, special characteristics, and religious practices) does not lead to trivialization.

As exposed in this paper, there is a long list of the diverse formulas adopted by monastic communities to manage and promote monasteries. Examples include accommodation (as much for leisure as a spiritual retreat), visiting the architecture or exploring the links with cultural heritage (events, museums, archives etc.), combining the visit with visits to other places or linking them to other agro alimentary activities.

The key element is the experience the visitor has of the visit. A word often used in this context is 'hosting' or taking people in, which is considered an obligation for the majority of monastic communities. When we talk about hosting, however, we have to differentiate between the infrastructure and human resources (reception staff or personal reception). Carreras Pera (1995) defines 'reception' as "infrastructure + maintenance + information = hosting".

Infrastructure is the basic level of hosting, and covers the superficial and material aspects. The word 'infrastructure' suggests a set of basic elements that allow a system to work. Monasteries have to be inviting, whatever their history, style, artistic wealth, simplicity, or geographical environment, etc. Each one has to affirm its own originality, personality, and function. The balance between simplicity, and a certain level of comfort, is not easy. Another aspect, which is just as important, is personal hosting. We have to distinguish between two different words: receive and host. Host is a stronger, warmer term than receive, as it supposes a personal, interior attitude. A welcoming attitude shows willingness to share, whereas someone who receives can be either passive or interested. Receiving does not require commitment, while hosting always implies obligation.

A welcome in artistic or historic places cannot be limited to just accurate historical or artistic information, but has to reveal an identity and a religious purpose. At the same time, it must try not to interrupt religious celebrations and program tourist visits in accordance with the requirements of worship.

All of this conditions the visitor experience. The nature of the experience in a sacred place is highly complex, above all because it is intangible and includes elements of nostalgia, closeness to God, atmosphere, the spiritual merit of the visit; all elements that have no economic value.

According to Sigala and Leslie (2005) the visitor experience depends on the personal meaning these spaces have (also conditioned by the previous images formed about the place) as well as events that take place and how these are developed. Many sacred places have a high number of repeat visitors. The same visitor, however, will not feel like returning if their experience was not entirely positive (too many visitors, entrance fee, lack of welcome, lack of cleanliness etc.) Satisfaction is an emotional, holistic response to a situation that is responding to expectations. Knowing what visitors want is of the utmost importance. This area, however, lacks data.

We have already seen that visitors to sacred places can be divided into those who have religious motivations and those who are motivated by tourism (of various kinds: heritage, monumental, cultural). In both cases, however, the main interest is centered on the visitor's experience, and how the visit converges with the spiritual message of the place; a concept Shackley (2001) calls 'spirit of place'. A visit to a sacred place means meeting something numinous, one of the challenges of the management is to maintain this feeling, this spirit, despite the influx of visitors. The key is to make tourists feel insignificant, excited and involved in "the spirit of the place", to enjoy an environment offering the opportunity to have an experience outside their normal routine. The lower the number of visitors, the easier is to manage the impact they have, to maintain the 'spirit of place', and to guarantee spiritual quality. Therefore, controlling the number of visitors is very important in sacred places that attract a large number of visitors.

Another concept affecting the visitor experience is that of authenticity. "The search for authenticity has become one of the key themes in the academic literature of tourism. MacCannell (1976), who initiated this discussion, emphasized the central role that tourist settings play in the search for authenticity. He noted that pilgrims' desire to be in a place associated with religious meanings was comparable to the attraction of tourists to places embedded with social, historical or cultural significance" (Belhassen, Caton, & Stewart, 2008, p. 668).

Sacred spaces, like heritage sites closely associated with the cultural identity of the local community, are places that can offer an authentic experience. The concept of cultural identity points towards a system of representation of the relationship between individuals and their land. The oral tradition is at the core of cultural identity, (language, sacred language, stories, songs, gastronomy), religion (collective myths and rituals, of which pilgrimages are examples) and formalized collective behavior.

Thus, enhancing monasteries through aspects such as gastronomy can be a tool to help improve the visitor experience of tourists; in so far as it is done while respecting the values these sites hold.

texto em

texto em