1 INTRODUCTION

This research aims to describe the components of the brand identity of Gramado, Brazil which contribute to the image of "model tourism destination", and verify if there is a strong link between the brand and the internal stakeholders of the destination. The objectives were set from the observation of the image that the Brazilian Ministry of Tourism (MTur), other Brazilian and international destinations, and tourists have of Gramado - as it is described following -, and the relationship found in the literature between brand image and identity.

The Report Brazil Experiences: learning from the National Tourism 2008/2009, of the benchmarking tourism project, states that Gramado is "[...] a management model and reference in the national tourism" (MTur, 2008, p. 50). The public policies on tourism (discussion on the municipal land use planning) stand out, as well as the tourism infrastructure, urban cleaning and public restrooms, public-private partnerships in the realization of events and the management of the 'Christmas of Light' for the innovation and inclusion of community. In 2010, there was another milestone in the project in which "[...] the development and management of thematic events stood out as a strategy for reducing the seasonality and also the use of theming for differentiation [...]". (MTur, 2010, p. 4).

On other occasions, managers of several places went to Gramado for benchmarking purposes. For example, the twinning agreement between Gramado and Óbidos, Portugal, enables benchmarking on the 'Christmas of Light' and other events of interest (PMG, 2008). With respect to the 'Christmas of Light', Gramado was visited by an entourage of Bragança Paulista, Brazil in 2013 (PMG, 2013a); by the Mayor of Iguape, Brazil in 2014 (PMG, 2014a); the Mayor of Ourinhos, Brazil in 2014 (PMG, 2014b). Still, in 2013, authorities from Caldas Novas, Brazil visiting the town considered Gramado a successful model of tourism and public management (Secom, 2013). In the same year, the Nigerian Ambassador to Brazil visited the destination to learn about tourism-driven economy (PMG, 2013b). During the Tourism Festival of Gramado in 2013, an entourage from Chile visited the City Hall to gather information about infrastructure, tourist attractions and events (PMG, 2013c).

Gramado is also considered a "model tourism destination" by tourists. The destination was awarded in 2010, 2011 and 2012 Best Winter Destination in Brazil, and Best Tourist Town in Brazil in 2011 and 2012, by the Viagem e Turismo (Travel and Tourism) magazine, from a survey conducted among the readers (PMG, 2013d).

Also, the importance of this research relates to one of the benefits of the brand identified by Clarke (2000): to provide a focus for a joint effort of producers, so that they can work for a common result. When promoting a destination as a single identity is relevant that all its attractions and tourism services, as well as the local community, are part of this identity. In this context, a brand identity can serve as a relational network of stakeholders within the place (Hankinson, 2004). The image of the destination should be favorable for all stakeholders, not only to customers. For this to occur, the relational network should ensure that the different stakeholders in tourism are able to express and discuss their issues and interact in order to direct efforts and achieve collective results (Saraniemi, 2010).

However, for Konecnik and Go (2008), the research on branding (creation and brand management) of destinations slightly overlooks the concept of brand identity, focusing on the perspective of the perceived image. This makes the research linking the ields of brand marketing and tourism little developed.

2 CONCEPTS AND THEORETICAL MODELS

For Reynolds (1965), the image is the tourist's mental construction of few impressions from many information of a tourism destination. Kotler and Gertner (2002) state that the image of a country can be activated in the minds of people by simply mentioning the name, even in the absence of brand management activities.

On its part, brand "[...] is not limited to a name on a label, but creates and adds a noticeable consumption value to the consumer" (Pimentel, Pinho & Vieira, 2006, p. 286). Within the brands, the product is not limited to its functionality, linking to that the worlds of meanings embedded in this (Norberto, 2004). Still, the brand is inscribed in a symbolic field that arose from a professional strategy, using the real, in order to create a competitive advantage in the market (Norberto, 2007). Karamarko (2010) adds that the brand portrays the identity of a destination.

For Karamarko (2010), the brand identity represents the associations that the brand wants to create in the minds of consumers. Aaker (1996) sustains that the brand identity represents the self-image and the desired image on the market of a product. Thus, it is understood that the brand identity of tourism destinations is formed by its characteristics, which internal stakeholders perceive and wish to convey in order to generate the image to tourists. Pimentel, Pinho and Vieira (2006) claim that image is a concept linked to the receiver while identity is linked to the sender.

According to Aaker (1996), the characteristics of the brand identity are not limited to product attributes, proposing four perspectives of brand identity: brand as product; brand as organization; brand as person; and brand as symbol. As for the brand as product it comprises: scope, attributes, quality/value, uses, users, and country of origin of the product. Scope is the association of a brand to a class of products, so that the customer call the class by the brand name. Attributes are the characteristics of a product that provide the customer with benefits. Quality is an extremely important attribute that is considered separately and is related to value, since the latter enhances the concept, adding the price dimension. Uses refers to the uniqueness of a particular use or application that some brands have. A brand can also be positioned depending on the type of users. And, finally, a brand can be linked to a country of origin, which would give it credibility (Aaker, 1996).

With respect to the brand as organization, this perspective includes organizational attributes, and local versus global. The attributes of the organization are more difficult to copy than product´s attributes, since they involve people, culture, values, and organizational programs, i.e. less tangible aspects than the attributes of the product. Referring to local versus global, when a brand chooses to be recognized as local, its tradition is emphasized to create a bond with customers and express pride, being more sympathetic towards the needs and attitudes of the locality. When a brand chooses to act global, it aims the prestige, a larger public and mission, and it projects a cosmopolitan personality. A global brand, in general, signals that it is advanced in technology, able to invest in Research and Development, and follow the advances in the countries wherein it competes. The role of the brand as organization is to provide credibility to their products or their sub-brands products (Aaker, 1996).

With respect to brand as person it includes: brand personality; brand-customer relationships. A brand can be described with adjectives much like the personality of an individual. Also, the brand personality can be the base upon which the brand-customer relationship is built (Aaker, 1996). De Chernatony (1999) also associates the relationships with personality, adding the interactions between employees, between employees and customers, and between employees and other stakeholders

And brand as symbol involves visual imagery/metaphors and brand heritage. The symbols, such as a figure, a color, a product design, facilitate brand recognition and recall (Aaker, 1996).

Karamarko (2010) thinks that Aaker's theory applies to tourism. As for Hankinson (2007), there are characteristics of destination brands that differentiate these from products and lead to differences in the way they are created, developed and maintained. Such features are: 1) co-production - there is a composite of individual services in a destination, being the product co-created by all parties involved; 2) co-consumption - the multifaceted nature of the place product leads to a simultaneous consumption by different customers for different purposes; 3) variability - each experience of the consumer of the place product is assembled individually from a variety of experiences and services on offer; 4) legal definition of the boundaries of place - the limits of the place are legally defined by Governments, which sometimes makes it difficult to offer a meaningful product that combines two or more locations; 5) administrative overlap - when there are differences between, for example, city and regional brands, causing confusion in tourist's mind; 6) and political responsibility -places fall within the responsibility of governments, whose members can be changed every election, which may result in decisions inconsistent with long-term goals. Parkerson and Saunders (2005) consider that the destinations also differ from corporate brands, because unlike corporations, a city has no organizational structure converging into a single focus.

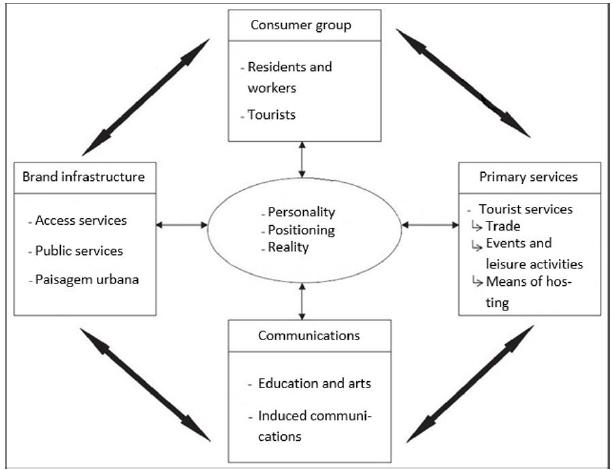

Considering the above-mentioned differences, in 2004, Hankinson had already put forward a specific conceptual model of destination branding (Figure 1), in which the author conceptualized brands as relationships. In this way, the brand has a personality that allows it to form a relationship with the consumer. Regarding services, there is interaction between service providers and consumers, and the encounter between them provides an opportunity for the development of a real relationship through the provision of a positive experience. For this, it is also necessary the relationship of the brand with the other stakeholders.

Hankinson (2004) posits that the product-experience cannot be controlled like a manufactured product. Consumer are free to choose which elements of the local product they want to consume. Because the destination is complex in terms of public and stakeholders, the branding must be coordinated, not managed. Herein lies the relevance of the brand as relationships, a feature addressed by Hankinson (2004). Different from Morgan and Pritchard's (2004) perspective, who stated that brand should be shared and "bought" by all stakeholders; Bregoli (2012) does not use the term "bought" to refer to the role of the stakeholders with respect to the brand identity of a destination, expressing that the construction of an identity is a participatory process rather than vertical: he reveals that brand identity guides the stakeholders' behavior if they believe in brand values, if that identity is coherent with the values of the destination and the local community. This is in line with Hankinson's (2007) above-mentioned concept of co-production and Pike's (2008) idea that the identity branding must come from research of the values of the host community, among other factors. Pike (2008) suggests that to achieve that a group project representative of the community should be formed.

Returning to Hankinson's (2004) model, which presents the components of the brand identity, it is referred to as the 'relational network brand'. It consists of a brand core and four categories of brand relationships.

The core represents the brand identity of a place and consists of personality, positioning and reality. The four categories of relationships are with: primary services, brand infrastructure, media, and consumers. Describing the brand core, Hankinson indicated that brand personality is characterized by functional attributes (tangible features, which meet environmental and utilitarian needs); symbolic attributes (intangible, which meet the need for social approval, self-expression and self-esteem), and experiential (linking functional and symbolic attributes together and which describe how the tourists' experience makes them feel). On its part, the brand's positioning is the identification of attributes that differentiate the tourism destination from other places. The context of the brand must ensure that both the personality and the positioning are rooted in reality, and a successful destination branding must not confine to creative marketing; the investments in facilities and services are essential, in order to reinforce the brand core values.

Hankinson does not restrict the brand identity to the communication plan, i.e. to the definition of personality and positioning included in the brand's promotion. The author agrees with Keller and Machado (2006, p. 7), whose vision is that, when the consumer trusts and is loyal to a brand, they expect it to provide them "[...] usefulness through the consistent operation of the product, in addition to adequate price, promotion, and distribution programs". Thus, it is important to include product strategies in branding, so that the facilities and services are in accordance with communication; distribution strategies, so that the transportation to the facilities and services are as promised in communication; and price strategies, to ensure that the rate charged is consistent with the quality and with the promotional message. Therefore, when Hankinson (2004) referred to his model as relational network brand and he designed it as a brand core and four categories of relationships, the author conveys that the relational network is formed throughout the whole process of branding. This includes planning, development, and implementation.

Regarding the four categories of brand relationships, primary services includes retailers, events and leisure activities, hotels and their associations. The brand infrastructure is composed of: access providers (internal transport and disposal), managers of hygiene facilities (public restrooms, street cleaning, car parks) and brandscape (built environment in which other services that are part of the core brand take place). The media include organic communication (the arts and education) and induced communication (advertising, publicity and public relations). Consumers include visitors (the target segments should not be conflicting); the residents (there should be compatibility between tourism and the interests of the community), and employees of local organizations.

3 METHODOLOGY

This is a qualitative and descriptive study and adopts the case study method. One of the features of case study is resorting to more than one source of evidence in the data collection, thus this work uses as collection techniques interviews with internal stakeholders (being the brand identity a concept associated with the sender) and additional research sources. The interviews include different groups of subjects: public sector; private sector; local community and employees. Among the sources of additional research there are the dissertation by Vargas (2003), in which the setting of the research is Gramado, and a reportage associated with the object of study. This allows a triangulation, and thus the development of converging lines of research, resulting in more conclusive and accurate results (Yin, 2010).

Twenty-one subjects were interviewed, since "in qualitative research the researcher's concern is not with the numerical representativeness of the group searched, but with the deepening of the understanding of a social group, an organization, an institution, a path etc." (Goldenberg, 2004, p. 14). That number was reached as follows. Initially, we sought to interview the target subjects of the MTur benchmarking program, who are responsible for some tourist organizations of Gramado, for conducting the main events in the destinations and for the association with the Casa do Colono (Settler's House). Taking into consideration the internal stakeholders presented in the Hankinson's (2004) model, it was necessary to interview subjects from the local community, tourism employees, and responsible for the infrastructure (public authorities). However, some of the companies from the benchmarking program refused interviews. Thus, besides the members of the organizations that agreed to participate, the representatives of all professional associations linked to Gramado's tourism companies were interviewed. Following the criteria of interviewing subject representatives of certain groups, we decided to interview representatives of the nine neighborhood associations of Gramado, although we only managed to contact four of them. A representative of the employees' class association was also interviewed.

For the reasons exposed next, the theoretical framework adopted is the Hankinson's (2004) relational network brand model. Considering that destinations are amalgams of products and services, which offer a total experience in a place, according to Buhalis (2000), and that Hankinson (2004) considers strong relationships with stakeholders the key for a successful experience, we believe that this is an appropriate model to characterize the brand identity of the destination. This is the general objective of the master's thesis of the first author of this article, in which she used the model of Hankinson (2004) in full.

However, due to the large amount of findings, in this article we only present part of these which were studied from some elements of the model of Hankinson (2004): the core brand and the relationships with internal stakeholders (public power - brand infrastructure; private sector - primary services; employees and local community - two of the brand consumer members).

The dissertation presented other models, such as those of Saraniemi (2010), Saraniemi (2011), Konecnik and de Chernatony (2013), which address the relations between stakeholders; but not as a central concept, differently from Hankinson (2004). Also, Hankinson (2004) specifies the stakeholders, contrary to Saraniemi (2010), Konecnik and de Chernatony's (2013) models, and the elements of brand identity.

Returning to the objectives, to describe the components of brand identity this study examines Hankinson's (2004) elements of the brand identity: personality, positioning and reality. For this, we asked the following questions: 1) Do you think that Gramado is a "model tourism destination"? 2) Which attributes does Gramado have that makes it a "tourism destination"? 3) Which are Gramado's top competitors in terms of tourism destinations? 4) From the cited attributes which differentiate Gramado from competitors? 5) What kind of tourist visits Gramado and your business?

Through the description of the identity components we verified if there were strong relationships between the brand and the internal stakeholders (public power, community, employees, and private organizations) that must share a common brand identity vision. Hankinson (2004) considers the residents and the companies' employees brand consumers. Also, the consensus between internal stakeholders is verified through the description of the elements of brand identity and a large agreement on these indicates strong relationships between them.

Regarding the organizational and analytical procedures, these draw on Bardin's (2004) content analysis techniques. The techniques used are the thematic analysis and categorical analysis. Firstly, the thematic analysis is carried out to identify the themes that make up the discourse of the subjects. It follows a comparison between the answers of the three groups of stakeholders found in the thematic analysis. Finally, the categorical analysis is done, grouping recording units (theme) in categories according to common characteristics (Bardin, 2004), and, in this article, based on the theories of Hankinson (2004) and Aaker (1996). Aaker's theory does not integrate "brand" and "destination", nonetheless, it was included due to the spontaneous appearance of organizational attributes of Gramado on the respondents' answers.

4 RESULTS

Through the interviews, it was verified that tourism marketing of Gramado is of the Municipal Secretary of Tourism responsibility. With regard to destination branding, Hankinson (2004) considers that the function of an entity is to coordinate rather than managing. That is because, unlike companies, whose production sectors are under the control of management, in a destination, the customer is free to choose which elements to consume; all products and services of the amalgam are co-authors in building the brand identity. Despite institutional promotion of the destination, there is still the dissemination and delivery of products and services by the components of the amalgam. Therefore, the answers of all internal stakeholders are considered.

In response to question 1 (Do you think that Gramado is a "model tourism destination"?) all answers were positive. They referred organizational attributes of Gramado (Aaker, 1996), such as attributes of the products and services, and attributes experienced by tourists in the destination (Hankinson, 2004), in response to question 2 (Which attributes does Gramado have that makes it a "model tourism destination"?), they reported the brand personality. Therefore, the thematic analysis of the answers unveiled 34 components of the brand identity of Gramado (Table 1).

Table 1 Summary of the discursive topics identified in the verbalizations of the subjects

| Public Power (PP) | Private Initiative (PI) | Local Community and Workers (CW) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Topics | Freq. | Topics | Freq. | Topics | Freq. |

| - | - | - | - | Threat to preservation (-) | 1 |

| Architecture | 2 | Architecture | 4 | - | - |

| Association with Europe | 1 | Association with Europe | 5 | - | - |

| Tourism attractions/ events | 3 | Tourism attractions/ events | 16 (1º) | Tourism attractions/ events | 10 (2º) |

| Beauty | 1 | Beauty | 4 | Beauty | 2 |

| Natural features | 2 | Natural features | 10 | Natural features | 11 (1º) |

| Charm | 1 | Charm | 2 | - | - |

| Community collaboration | 6 (2º) | Community collaboration | 8 | Community collaboration | 2 |

| - | - | Over construction (-) | 1 | Over construction (-) | 1 |

| Credibility | 3 | Credibility | 7 | - | - |

| - | - | Efficient complementarity of the tourism product | 5 | - | - |

| - | - | Elegance | 1 | - | - |

| - | - | Delightful | 5 | - | - |

| Entrepreneurship | 3 | Entrepreneurship | 1 | - | - |

| - | - | Sewage (-) | 1 | Sewage (-) | 1 |

| Public Management | 3 | Public Management | 2 | - | - |

| Hospitality | 4 (4º) | Hospitality | 13 (2º) | Hospitality | 7 (3º) |

| Imagery of Gramado as a non-Brazilian place | 1 | Imagery of Gramado as a non-Brazilian place | 13 (2º) | - | - |

| General infrastructure | 2 | General infrastructure | 4 | General infrastructure | 1 |

| Infrastructure/ tourism services | 5 (3º) | Infrastructure/ tourism services | 12 (3º) | Infrastructure/ tourism services | 2 |

| Innovation | 7 (1º) | Innovation | 14 (1º) | Innovation | 3 (4º) |

| Cleanliness | 2 | Cleanliness | 7 | Cleanliness | 2 |

| A little expensive (-) | 2 | A little expensive (-) | 1 | A little expensive (-) | 1 |

| Modernity | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| Organization | 2 | Organization | 3 | Organization | 1 |

| - | - | - | - | Loss of tranquility (-) | 1 |

| Products of origin | 4 (5º) | Products of origin | 5 | Products of origin | 2 |

| - | - | Professionalism | 4 | Professionalism | 2 |

| Quality of life | 2 | Quality of life | 2 | Quality of life | 2 |

| Organizational quality | 1 | Organizational quality | 5 | - | - |

| Romantic | 1 | Romantic | 1 | - | - |

| Safety | 3 | Safety | 6 | Safety | 3 (4º) |

| Tranquility | 1 | Tranquility | 4 | Tranquility | 3 (4º) |

| Traffic/ mobility (-) | 1 | Traffic/ mobility (-) | 4 | Traffic/ mobility (-) | 2 |

Source: The authors

It is pertinent to refer that two subjects of the public authorities, two of the private sector, and one from the community and employee stated that Gramado is "a model tourism destination" due to various factors. The subject 1 (PP) explains: "[...] we can find a detail more beautiful elsewhere, an element, but not the set. [...] It's not one thing, it's not a waterfall, is a set ". For Bahl (2004), the existence of attractions is not enough for tourism, it is necessary to combine them with ease of access and the permanence of tourists, thus making them tourism products. The subject 7 (PI) says: "In Gramado there is a set of things combined to get the result [...] we receive a lot of technical visits at Christmas of Light. [...] to copy a garland, a snowman [...] do the same in their hometown, but it won't have the name Gramado behind." This concurs with Kotler's (2009) perspective that if there is an exclusive "tapestry" of powerful strategies, based on a unique configuration of various activities that are mutually reinforced, the competitors can imitate certain aspects, but not the whole "tapestry". To imitate everything, competitors will have high expenses and will produce a pale imitation, without achieving the same performance.

The most cited attribute by the three groups of stakeholders was tourism attractions/events (29 events), due to the large number and innovation. Many options are offered to the visitor all year long to avoid seasonality and to increase the length of stay. Regarding innovation of tourism attractions/events, novelty (Johannessen, Olsen & Lumpkin, 2001) is focused on creating themed parks and events. Theme parks like the Snowland (with artificial snow) was referred often. For example, the subject 10 (PI) explains that among: "[...] the major points of interest, the most recent wherein Gramado has innovated is the Snowland, which brought to Gramado a new way to enjoy the snow, regardless if it's 40 degrees on the street." Vargas (2013) reports that theme-based events in Gramado contribute to the "disneyfication", since Walt Disney World parks, in the United States, influence the Christmas of Light and the Chocofest. The subject 13 (PI) likened Gramado to Disney parks due to the themed events. Thus, in addition to the association of Gramado with European imagery, there is also this "disneyfication".

Tourism attractions/ events still appear as one of the attributes (the other is general infrastructure) that differentiate Gramado from competitors (positioning), in response to question 4 (From the cited attributes which differentiate Gramado from competitors?). The competitors mentioned in response to question 3 (Which are Gramado's top competitors in terms of tourism destinations?) are national highlights (Rio de Janeiro, Sao Paulo and Foz do Iguaçu), a winter destination (Campos do Jordão), and towns in the region (Bento Gonçalves and Canela), according to the reports: "[...] unique in several factors, particularly, in terms of events "(subject 3, PP); "What it has is the unique experience [...] to be in a place that has all the things that you would like, not to mention the events [...]" (subject 12, PI); "Christmas of Light, in which other municipalities are not investing" (subject 16, CW); "[...] things that other cities don't have, [...] the Snowland, [...]" (subject 18, CW); and "[...] has several attractions. It's all year long, every month, at least, there is an attraction. Unlike any other place." (Subject 19, CT)

Now we compare the topics of the three groups of respondents to verify if there are strong relationships between the brand and the internal stakeholders. Most of the topics are repeated in the three groups. Those which appear in only one group are: elegance, efficiency and complementarity of the tourism product, modernity, threat to preservation, loss of tranquility, and delightful - 20.59 percent of the total. Some of these topics appear as well in the reports of the other groups in different words, such as Efficient complementarity of the tourism product (satisfactory performance of all on the supply chain), cited by five subjects of the private initiative who claim that the public authorities and entrepreneurs contribute to efficiency; the subjects of Public Power cited the efficiency of the public administration and entrepreneurs separately. For example: "[...] the private sector invests in the establishments and the public authorities take care of the city" (subject 4, PI); "The municipality doesn't invest, but created the conditions for businesses to do so." (Subject 1, PP); and "Our cuisine is very diverse. Our hospitality too, we have over 11,000 bed spaces. We have the best tourist infrastructure of Rio Grande do Sul. Also the stores have a qualified context [...]." (Subject 2, PP).

Threat to preservation, referred by the subject 17 (CE), is associated with the topic over construction, pointed to by 12 subjects (PI) and 18 (CE), as they both refer to the reduction of vegetation due to the growth of the city. Loss of tranquility - too many people in the high season -, pointed to only by the subject 17 (CE), is associated with tranquility - present in other periods - (cited by one of the subjects of the Public Power, four of the private initiative, and three from the local community and employees); and traffic/ mobility, because traffic congestion causes stress.

As to the target markets of Gramado (part of the destination brand personality) we present in Table 2 the elements cited in alphabetical order and separated into sets, in response to question 5 (What kind of tourist visits Gramado and your business?). It is noted that as to interest, groups, and the age of tourists, the answers of the three types of respondents are similar. Most visitors seek entertainment, other go to congresses/ trade fairs. Many people travel with family, particularly during the Christmas of Light (October to January), there are also many groups coming through tour operators or excursions. The ages are varied. In general, the town is not the destination of choice for young people looking for nightlife, except during the Film Festival in August. On the other hand, some attractions are popular among students, as the Gramado Zoo.

Table 2 Summary of Gramado target markets as indicated by the respondents

| Public Power | Private Initiative | Local Community and Employees | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Topics | Freq. | Topics | Freq. | Topics | Freq. | |

| Interest | Congress/Trade fairs | 2 | Congress/Trade fairs | 4 | Congress/Trade fairs | 1 |

| Leisure | 3 | Leisure | 11 | Leisure | 5 | |

| Honeymoon | 2 | Honeymoon | 6 | Honeymoon | 1 | |

| Groups | Family | 3 | Family | 9 | Family | 5 |

| Tour agency | 1 | Tour agency | 4 | Tour agency | 2 | |

| Excursion | 1 | Excursion | 1 | Excursion | 4 | |

| Age | Children | 1 | - | - | Children | 1 |

| - | - | Young people | 2 | Young people | 1 | |

| - | - | Adults | 3 | Adults | 1 | |

| Elderly | 1 | Elderly | 3 | Elderly | 1 | |

| - | - | - | - | All ages | 2 | |

| Social Class | A, B, C e D | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| - | - | A, B e C | 1 | A, B e C | 3 | |

| - | - | B e C | 2 | - | - | |

| Massified | 1 | Massified | 1 | - | - | |

| - | - | Change in profile. Until recently various classes were coming. Poor quality may not attract the upper classes | 1 | - | - | |

| - | - | Change in profile. Possibility of the target markets AA, A and B run from crowd | 1 | - | - | |

| - | - | Participants in congres-ses/trade fairs with higher income (A and B) | 1 | - | - | |

| - | - | Low purchasing power during big events | 1 | - | - | |

| All/ various social classes | 1 | All/ various social classes | 2 | All/ various social classes | 2 | |

Source: The author

There are differences with regard to the social class of the visitors. Several social classes were referred, being in agreement with the subject 2 (PP) who considered that destination marketing is not targeted at a specific segment. The target are the upper class tourists, for example, when promotional brochures refer to the luxury and create a high-quality souvenirs brand; at the same time, the authorities promote among other segments (i.e. excursionists - those who do not spend the night) the various attractions of Gramado and the options in terms of budget accommodation, in an attempt to increase the length of stay and the use of tourism facilities.

This is also the perspective of other public managers, according to the subject 13 (PI), who claimed that plans for new accommodation facilities have been approved, representing more 9,000 bed spaces in five years, what, for him, results in accumulation of people, pushing away upper class tourists. Mariano (2013), reports that in that year there were 25 projects for new hotels or guest houses waiting for the Mayor's approval, and just the larger projects accounted for more than 5,000 bed spaces in destination (half of the beds until then). At the time, it was decided for the non-approval of new hotels with more than 30 rooms for 90 days, because it was believed that too many projects would cause medium-and long-term impacts. There were already problems, namely: traffic congestion; lack of parking spaces; queues at restaurants on weekends; a modification in the destination features due to over construction; and the high number of empty beds off-season (around 40 percent). During the moratorium, the Municipal Plan would be re-evaluated, and a commission of experts would be formed to propose rules and to consult the Plan Committee (which included some professional associations in the area of tourism and some members of neighborhood associations).

The subject 13 adds that the target segments AA, A and B search for quality services, threatened by the increasing supply of hotel rooms with the consequent drop in prices. For him, the trend is that only those who spend little will attend the city in large numbers:

There is a project of 300 apartments to be divided into 12 quotas. It makes 300 times 12 to see how many people that is. And these apartments have kitchen. So, first of all, these people don't come to a hotel; secondly, they don't go out to eat. [...] 300 families that will only spend with grocery shopping. Is not the same thing as if you do the cost-benefit ratio of the cost they represent to the town and we're going to be subsidizing a good part of what they consume in the public service.

This shows that marketing is not limited to promotion, as Keller and Machado (2006) refer, rather it includes product, price and distribution strategies consistent with promotion. A product strategy put forward by the authorities of Gramado to enhance the competitiveness of the hotels on the market with oversupply is investing in innovative companies, thematic or installed in the rural area (Mariano, 2013). This concurs with Porter's (1989) differentiation strategy: to develop unique products by highlighting a peculiar feature or other factors.

Regarding the excursions, the subject 17 (CE) refers that the people from Gramado dislike the large number of them in the Christmas of Light, and their low spending. However, he believes that even lower classes benefit the destination. The subject 12 (PI) confirms: "the Chocofest was widely criticized because the businessmen say, not all of them, that Chocofest doesn't attract clients with good purchasing power. The same happens with the Christmas of Light." Also the subject 12 mentions the lack of strategic planning involving all stakeholders and considers it a solution for the mobility problems: "There is no strategic planning, things just happen. Institute fares for the circulation of buses [...]. The city is small and, sometimes, it doesn't have room for all this crowd. Some things are consensual and others aren't. There is no unanimity." The interviewee understands the importance of consensus among the stakeholders as to the public of Gramado, which is part of the brand identity and is connected to other identity features, such as mobility. This is because, as stated by Buhalis (2000), a destination is an amalgam of products and services that provides a total experience to tourists; thus, if each component transmit a distinct identity, that will reflect on the visitors' perception on the overall experience. And therefore, Hankinson (2004) posits that the relational network must be present during the entire process of branding, from planning to implementation. Because the destination is a complex of publics and stakeholders, in which each consumer is free to choose the elements to consume (the "product experience" cannot be controlled in the same way that a manufactured product is), the branding must be a coordinated, unmanaged process, so that stakeholders have proactive role in the construction of brand identity.

Despite the similarities of the attributes mentioned, there are noticeable differences between the internal stakeholders and the visitors, which indicate weaknesses in the relationships between them. There is a lack of strategic planning, each element does what believes it is their part, but does not act to gether.

What is mention here is not the judgement about whether it is better to attract higher or lower class tourists, but the existing conflict regarding the high season, between the characteristics of the brand identity of Gramado caused by the lack of a precise definition of the target audience. For Hankinson (2004), a destination should not attract groups of visitors with conflicting needs, as, for example, attract to a busy destination people seeking tranquility. Also, defining the target audience is relevant for decision-making related to other characteristics of the brand identity, which, in Gramado, are: infrastructure quality/ tourism services; price; general infrastructure, mobility; and natural features, linked to overbuilding and the accelerated growth that has destroyed vegetation.

However, the precise definition of the target audience is difficult when it comes to tourism destinations, given the different natures of their stakeholders. Organizations have more flexibility to choose their target audience, and the profit can come from both quantity and quality of services. That is possible because they have the right to free enterprise, present in the Federal Constitution of Brazil (1988); which Garcia (2008) defines as the guarantee that everyone has to free creation and management of enterprises, which includes the freedom to determine how the activity will be developed, the form, quality, quantity and price of their products or services. However, the public authorities have a greater social role, and they cannot guide their choices only considering the profit that tourists bring to the destination and the consequent increase in tax collection aimed at the well-being of the population and tourists.

Their role goes beyond the welfare of the society wherein they operate and, according to the Article 23 of the Federal Constitution/88: "The Union, the States, the Federal District, and the municipalities, in common have the power: X - to fight the causes of poverty and the factors leading to substandard living conditions, promoting the social integration of the unprivileged sectors of the population". Therefore, a destination should be open to all. Still, the existence of popular events such as Christmas of Light, contributes a great deal to the formation of the image of Gramado as a "model tourism destination" and makes the destination competitive in face of the coastal destinations during the summer.

Therefore it is important that the different stakeholders can discuss their issues and interact as Saraniemi (2010) suggests. All the local community must participate, even those who do not work directly with the tourism, when considering a destination as an amalgam. In addition, according to Bregoli (2012), the construction of identity is a process more participatory rather than vertical. Pike (2008) suggests the formation of a community group project for that construction.

In Table 3, the topics are divided into categories (functional attributes, symbolic attributes, experiential attributes and organizational attributes) and in their respective sub-categories, defined according to Hankinson (2004) and Aaker (1996).

Table 3 Categorical Division of the destination attributes

| Categories | Sub-categories | Freq. |

|---|---|---|

| SYMBOLIC ATTIBUTES | Hospitality/service (+) | 24 |

| Leisure | 19 | |

| All social classes | 18 | |

| Family groups | 17 | |

| Non- Brazilian imagery (+) | 14 | |

| Children, adults, and elderly | 11 | |

| Honeymoon | 9 | |

| Congresses/trade fairs | 7 | |

| Tour agency groups | 7 | |

| Excursion groups | 6 | |

| Europeanization imagery (+) | 6 | |

| FUNCTIONAL ATTRIBUTES | Tourism attractions/ events (+) | 29 |

| Natural features (+) Vegetation, climate, relief, Lago Negro (Black Lake), rural area, etc. | 23 | |

| Tourism infrastructure/ services (+) | 19 | |

| Products of origin (+) | 11 | |

| General infrastructure (-) Transportation network/traffic/mobility | 7 9 | |

| Sewage | 2 | |

| General infrastructure (+) Neighborhoods' atmosphere, sidewalks, flowers, etc. | 7 | |

| Architecture (+) | 6 | |

| A place a little expensive (+) | 4 | |

| Natural features (-) Vegetation/over construction and threat to preservation | 3 | |

| ORGANIZATIONAL ATTRIBUTES | Innovation (+) | 24 |

| Cooperation of the community (+) | 16 | |

| Credibility (+) | 10 | |

| Professionalism (+) | 6 | |

| Organizational quality (+) | 6 | |

| Efficient complementarity of the tourism product (+) | 5 | |

| Public Management (+) | 5 | |

| Entrepreneurship (+) | 4 | |

| EXPERIENTIALATTRIBUTES | Safe (+) | 12 |

| Clean (+) | 11 | |

| Tranquil (+) | 8 | |

| Beautiful (+) | 7 | |

| Organized (+) | 6 | |

| Quality of lifedade (+) | 6 | |

| Delightful (+) | 5 | |

| Charming (+) | 3 | |

| Romantic (+) | 2 | |

| Elegant (+) | 1 | |

| Modern (+) | 1 | |

| Loss of tranquility (-) | 1 |

Source: The authors

The stakeholders of Gramado associate to the image of a "model tourism destination" mainly symbolic attributes (138 occurrences, 35.57 percent) and functional attributes (111 cases, 28.61 percent). The difference between these categories of attributes does not reach 10 percent. On the other hand, the sum of the percentages of organizational attributes (76 occurrences, 19.59 percent) and experiential attributes (63 occurrences, 16.24%) is 35.83 percent, less than one percent difference from symbolic attributes. This shows the relevance of the categories with the highest percentages for the construction of the brand identity of Gramado. It is natural that the symbolic attributes have the highest frequencies, because as Norberto (2007) points out, the brand is inscribed in a symbolic field. This author, in 2004, has pointed out that through the brand a product becomes more than its functional properties, it includes the worlds of meanings embedded in it.

It was noted that there is an intrinsic relationship between the symbolic and functional attributes regarding the definition of target audience (symbolic attribute). Such definition affects the decisions relating to other features of the brand identity, for example quality of the tourism infrastructure/services, price, general infrastructure and natural features, which are functional attributes.

5 FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

The findings show that the image of Gramado as a "model tourism destination" is constructed through branding. Such identity is composed of 34 elements. The most mentioned attribute for all three groups of stakeholders interviewed is tourism attractions/events, with 29 occurrences. This attribute is also a differentiation factor of Gramado from other competitors (positioning) - which, in general, are Brazilian tourism destinations. The attributes were divided into four categories: symbolic attributes (35.57 percent), functional attributes (28.61 percent), and organizational attributes and experiential attributes on a smaller scale.

It was also verified, by comparison between the topics mentions by the three groups of stakeholders, that there are weaknesses in the relationships between internal stakeholders due to the differences found, especially with regard to visitors' social class. It has been found that, currently, the marketing of Gramado is not directed to any specific target audience in terms of social class. However, some subjects in this study would like the marketing strategy to be targeted at the AA, A and B classes, while others do not consider a restriction. Also, one of the respondents pointed to a lack of strategic planning that would set the target audience. This divergence is reflected in a conflict between the characteristics of the brand identity of the destination, as, for example, between massification and quality of the tourism infrastructure/ services. Therefore, it is important to define more precisely the target audience. However, this definition is difficult to make when it comes to tourism destinations, given the different natures of the stakeholders.

We can highlight some contributions of this research to the knowledge on destination branding: 1) the identification of difficulties in defining the target audience of the brand-destination due to the different natures of the stakeholders, which demonstrates the significant distinction between this type of branding and branding in general; 2) in addition to the functional, symbolic and experiential attributes - adopted by Hankinson (2004) -, organizational attributes were noticed as part of the brand-destination and also important in branding. These simple contributions point to the need for further research on this topic, and it is suggested more research on the definition of target audience, leading to deeper considerations. This research is not an end in itself; it unfolds new paths to be followed in this field of knowledge.

texto em

texto em