1 INTRODUCTION

This article is part of a research project on hospitality mediated by the social networking service (SNS) Couchsurfing. This practice consists of staying overnight in someone else’s "living room" while travelling. It is a network of hospitality in which its members (surfers), as hosts give shelter for a few days, freely and without charge, to other guests.

The concept of Couchsurfing was created by Casey Fenton, an American, together with other founders of this SNS. It all started with an email to students in Iceland in the context of an event, asking for lodging in their homes, which would provide psychological and physiological comfort (Figueiredo, 2008). In return, the creator of Couchsurfing would offer his cultural experience to the potential Icelandic hosts. The search for an alternative lodging sought to avoid the standards established by the market and travel agencies, common intermediaries in hospitality.

At first, Couchsurfing was a non-profit SNS offering the advantage of free accommodation worldwide without any additional cost or obligation. However, according to information on the network’s website, as of 2011 an annual fee of 18 euros was established. This fee is to cover the costs of validating the profile of each registered person, providing greater safety to about 12 million users of the network, spread over 200 thousand cities. In that same year, the mission of "creating travel experiences based on exchange, generosity, interpersonal trust and cultural exchange" was added to the website. (http://www.couchsurfing.com/abo ut/about-us/).

Some studies on Couchsurfing have already been carried out by researchers from various countries and perspectives. Bialski's research (2007) related the Couchsurfing practice to "Intimate Tourism", an expression that designates a system of exchange in which travel experiences and relationships are shared in different spaces, such as those created by online networks, and not only in the spaces of traditional tourism. Other publications discuss the interpersonal trust of the individuals enrolled in Couchsurfing from their interactions (Bialski & Batorski, 2010; Shapiro, 2012; Cherney, 2014); as well as barriers to using Couchsurfing considering, particularly, the profile of users and their positive and negative references (Bradbury, 2013, Liu, 2013 & Yannopoulou, 2013). Zhu (2010), in turn, studied the members registered in SNS without couch surfing experience, either as host or as a guest. Research results from Ronzhyn (2015) emphasized the connection between trust and experience on Couchsurfing, where more experienced users are the most reliable.

Couchsurfing was also the object of some studies carried out in Brazil. Figueiredo (2008) sought to understand the worldviews outlined in the system of exchange between guests and hosts, which led to reflections on the gift, tolerance, and imagery of travel. On a related note, a study examined Couch-surfing users’ profile in a quantitative and qualitative survey (Dutra, 2010). The results indicated that the predominant profile consists of young people with a mean age of 28.5 years, speaking around 3.87 languages. The knowledge of these studies, as well as experience as a Couchsurfing guest in Jaguarão, Rio Grande do Sul State (RS), has sparked interest in the research from which this article derives.

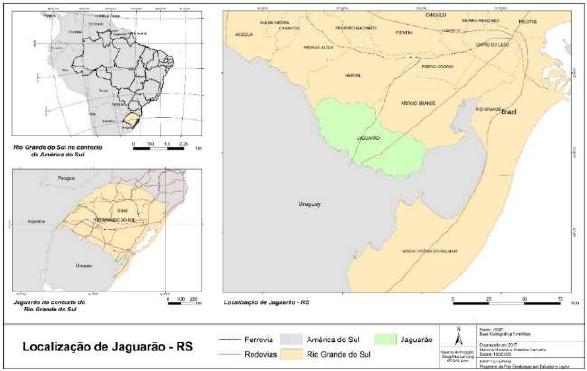

As shown in Figure 1, the municipality chosen as reference for the research is located in the Jaguarão micro-region and is 395 km from Porto Alegre. In Brazil, it borders the municipalities of Arroio Grande and Herval and, in Uruguay, the municipalities of Rio Branco and Lago Merín (Cunha, 2012).

Source: IBGE (2017)

Organization: The authors

Figure 1 Location of Jaguarão, Rio Grande do Sul State

According to the Brazil Institute of Geography and Statistics - IBGE (2017) Jaguarão has an estimated population of 28,230 inhabitants, occupying around 2,051,021 Km2 and its economy revolves around agriculture and services. However, as of the opening of the duty free stores in Rio Branco, in 2003, there was an increasing flow of tourists to the Uruguayan city, with Jaguarão emerging as a "commuter town". Some features give Jaguarão a subtlety in its historical, social, and cultural formation, towards the time in which Brazil and its neighbors fought for territory. The landscape and historic ensemble is protected by the Brazilian Historical and Artistic Heritage Institute (IPHAN) since 2010. According to Ribeiro and Melo (2011) "this is the highest number of protected buildings in the State of Rio Grande do Sul, with more than 800 units".

In addition, Jaguarão has become a university town, with the establishment of the campus of the Federal University of Pampa, in 2008. Thus, many students having passed the Brazilian High School Exam, ENEM, temporarily move to Jaguarão, becoming residents in the municipality while graduating. It is important to emphasize that Jaguarão has several restaurants that tend to value the local gastronomy (the barbecue), in addition to having about 20 accommodation establishments, among hotels and hostels (Prefeitura de Jaguarão, 2017). Besides these lodgings, Couchsurfing is common there, what bring us to home exchanges of "sofa" in the domestic context. According to Lashley & Morrison (2006), social relations and the way in which individuals interact with one another in the perspective of hospitality mediated by new technologies are worthy of attention.

The concept of hospitality is central to research and recurrent theme in tourism practices, as pointed out by Panosso Neto (2013). Some authors, such as Camargo (2004), base their studies and research on the French approach to hospitality, in which the "theory of the gift" proposed by Marcel Mauss (1974) is a key reference. For the French anthropologist, the expression "give, receive and reciprocate" is a relation that symbolizes the exchange. By offering a treat or gift to someone, the gesture itself forces the recipient to reciprocate. For the author, reciprocity exist, albeit indirectly. In this way, the gift justifies the cordiality, relationships, and human conversations in each society. Perrot (2011) also envisages hospitality as a gift and seeks to understand the connections and exchanges between the host and the guest.

In the same vein, Camargo (2006) considers the tourist activity as an overlap of two systems of exchange and emphasizes the virtue of the gift that persists in the commercial scope: one of system is governed by the contract, by what is agreed upon by the parties, and the other is ruled by the gift, i.e., by what is not formally agreed, and therefore something difficult to achieve by simple observation. For the author, hospi-tality means the act of welcoming the other in all its dimensions: provision of shelter, security, food, entertainment during the stay in a certain place (Camargo, 2011). Godbout (1999), in turn, calls hospitality the "gift of space", space that creates and provides sociability.

These fundamentals are relevant to understand the social practices embedded in the phenomenon of hospitality, such as Couchsurfing in the extreme south of Brazil - whether directly or mediated by a virtual platform, from a distance. In this sense, the objectives of this article are to identify and discuss the main interests and motivations for the network and Couchsurfing travel, among the hosts and guests in Jaguarão, as well as to understand the system of exchanges between guests and hosts, inspired by the studies of hospitality based on Marcel Mauss’s theory of the gift.

2 METHODOLOGY

This study adopted a qualitative design using a set of interpretive practices (Maingueneau, 2000) and was essentially focused on the understanding of hospitality from the social practices mediated by a worldwide SNS of travelers in Jaguarão, RS. To this end, a literature survey, and a virtual field research based on nethnography, which is, according to Kozinets (2014), an ethno-graphic approach for digital media.

The coming of the Internet has posed a significant challenge for our understanding of research methods. Across the social sciences and humanities people have found themselves wanting to explore the new social formations that arise when people communicate and organize via email, websites, mobile phones and the rest of the increasingly commonplace mediated forms of communication. Mediated interactions have come to the fore as key ways in which social practices are defined and experienced. (Hine, 2005, p.1)

The choice of nethnography led to immersion in the field of research, which, after register on the Couchsurfing network, made possible the virtual observation and the instrumental search in the network.

[…] observing an Internet discussion list or a virtual community on a social networking site will bring materially distinct data (such as written texts, emoticons, images, and links published by users, for example) from those collected in face-to-face meetings. For some, this difference justifies the use of terms such as "virtual ethnography" and/or "nethnography", highly-ghting the difference from "pure" ethnography. (Polivanov, 2013, p.6-7)

At first, the challenge was to identify all the subjects with registered profile, with house or who had stayed overnight with hosts in Jaguarão, RS. The number totaled 40 surfers. From then on, we looked through the profiles of these subjects to know them, to interpret their images and styles, codes, likes, and dislikes. This virtual observation, characterized as "online wandering", was the first contact with the subjects involved in SNS Couchsurfing in the mentioned municipality.

Then individual contact was made with each surfer selected, through asynchro-nous communication (message or email), inviting them to participate in the survey as volunteers. The positive feedback was given by 13 surfers from the social network: 8 hosts and 5 guests, for whom the Free and Informed Consent Form approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Minas Gerais was sent, as well as a script of the interview to be conducted later, either face-to-face or with the help of virtual tools. Each volunteer used a pseudo-nym for anonymity: the hosts are Storck, Bird, Guru, Carlito, Fafá, Bee, Minervina, and Leo; and the guests are Potosi, Teo, Pucek, Flavnav, and Bitmary.

This non-probabilistic sampling was "determined by typicality and convenience" (Laville & Dionne, 1999, p.170), considering the subjects readily available and accessible to participate voluntarily in the research, in the indicated period. The interviews via skype were done using the software Pamela to record and save all the visual and spoken script, for subsequent transcription.

The interpretative analysis conside-red the vision, principles, and policies of the SNS Couchsurfing and is consistent with studies of hospitality, especially those based on Marcel Mauss’s (1950, 1974) theory of the gift. This theory played an important role in the understanding of the way in which exchanges take place and the possibilities of maintaining social bonds either in the network interactions or at the homes, symbolized by the couch metaphor. The theory was used, therefore, to clarify the treatment of the data collected through interviews, based on Godelier’s (1996, p.7) perspective that "the gift-giving exists every-where, even if it is not the same everywh-ere".

Tourism, considered as an amalgam in which consumer protection laws are set out in contract clauses, is also governed by the ancestral laws of gift giving (Camargo, 2006). Thus, other observations that refer directly to the research objectives, based on the main results of previous research, were also included in the interpretative analysis of the data collected, as will be discussed below.

2.1 Dynamics and perspectives of SNS

According to Luz (2012), growing individualism in the last decades has led to a fragmentation of the human being. However, simultaneously, as social beings, we need bonding, which lead us to seek in the act of traveling some intimate and meaningful social bonds. It is a paradox of "post-moder-nity": freedom creates individualism, but brings with it the solitude and the lack of affection, which are remedied by reinte-gration.

Bauman (2003) points out that, although communities are increasingly ephemeral and occasional, the appreciation of the other and closer ties become necessary. The author stresses:

If a community is to exist in a world of individuals, it can only be (and must be) a community woven together from sharing and mutual care; a community of concern and responsibility for the equal right to be human and equal ability to act in that right. (Bauman, 2003, p.134)

One of the technological advances that allowed for the dissemination of this social behavior was the Internet and, in the specific case of tourism, the use of social networks aimed at travelers. Vila & Vila (2012) argue that the novelty is not in access to the diversity of information made available through the Internet, but in the search and ways of managing this informa-tion, making it more appealing. Web 2.0 technologies made possible the develop-ment of blogs, image galleries, social media, and other tools.

According to William & Martell (2008), tourism 2.0 uses similar platforms interrelated with a network system. Knowle-dge and its dissemination must be the network’s driving-force, that self organizes and develops through the systemic feedback of its users. Hence, tourism systems are not linear. They operate in a complex, dynamic, uncertain, and unpredictable way, influenced by direct elements of the tourist activity, and indirect and external to the network, such as culture, politics, and social, natural and human resources. In order to maintain pro-per functioning of tourism systems, a differ-entiated management with monitoring and social learning is required for adaptation to changing scenarios.

The systematic orientation of the networks shapes the social relations through the horizontal structure, in which there is no social hierarchy, since all users are consumers and producers of information (Castells, 2003). In this way, information reaches many people and the sharing potential increases. For this to happen, according to Alves (2011), relationships must be based on trust, which is tied to the individual's knowledge of a subject. The deeper the knowledge, the greater the trust. Otherwise society disintegrates.

It is against this background that social networks such as Couchsurfing appear, significantly changing the users’ search and experience of lodging. Couchsurfing is the voluntary and temporary displacement of people or groups, for leisure or other reasons, generating interpersonal, social, economic, and cultural relationships. It is a contemporary practice that seeks deep personal experiences linked to happiness (Stern, 2009). This practice is made possible by access and registration on the website, and in these conditions the tourist is seen as a guest, not as an outsider, in Bialski’s (2007) understanding.

The SNS Couchsurfing encourages people to welcome one another in their homes and to become both guests and hosts. Technically, because no contractual or financial ties exist for the provision of the service, the creators of this idea of hospitality exchange have put forward their own rules. The "About us" link on the website explains Couchsurfing's values, principles, and policies:

Vision: We envision a world where everyone can explore and create meaningful connections with the people and places we encounter. Building meaningful connections across cultures enables us to respond to diversity with curiosity, appreciation, and respect. The appreciation of diversity spreads tolerance and creates a global community.3

The principles established by the common use of SNS Couchsurfing outline guidelines that are materialized - or, should be materialized - in the scope of social practices, also offline. These practices begin in the request for lodging:

Share your life: Couchsurfing is about sharing your life your experiences, your journey, your home, your extra almonds or a majestic sunset. We believe that the spirit of generosity, when applied liberally, has the power to profoundly change the world.

Create connections: Connection makes us happier; we need more of it. Connecting with and accepting the kindness of “strangers” strengthens our faith in each other and helps us all become better people.

Offer kindness: Tolerance, respect and appreciation for differences are embodied in kindness.

Stay curious: We appreciate and share a desire to learn about one another, about the world and about how we can grow as people and become better global citizens through travel.

Leave It Better Than You Found It his applies to the world, to relationships, to your host’s home or to the sidewalk you meander down on your way to the coffee shop. We’re here to make the world better, to enhance each other’s lives and to become stronger in that purpose by coming together4.

In this interaction mediated by new technologies, what leads a host to receive a guest, through Couchsurfing? What motivates a surfer to request lodging in Jaguarão, in the extreme south of Brazil? These were some of the questions made to participants during the interviews, as will be discussed below.

2.2 Between the real and the virtual: the threshold paradox

Alain Montandon, in the foreword to Le Livre de l´hospitalité (2011) reveals the threshold, where usually we find a mat, the main door, and doorbell. The threshold would thus be a border between the interior and exterior of the house where new conditions and rules are unveiled to make guests feel at home in an unfamiliar environment. In this sense, we sought to understand the meanings of the "threshold" for Couchsurfing users in Jaguar, and to know the reasons why users registered in this network.

The first host interviewed was Storck, a young university student from Manhuaçu, Minas Gerais, who moved to Jaguarão in 2013 for school and has since maintained his membership in the network of travelers. In his profile as a surfer he stressed that "[...] believes in the power of the plural and it is by sharing and exchanging experiences that one builds character and a better personality." In the interview he added the main purpose of his registration on the site:

I’m a student of Production and Cultural Policy at the Federal University of Pampa and work in theater in an intuitive way. Couchsurfing, inclusively, is fundamental to interact with different people, which helps my formation in this sense. (Storck, aged 30, Minas Gerais State).

To a certain extent, this account underlines the principles of Couchsurfing, namely the possibilities of creating and generating significant connections with people and places, in addition to expanding the artistic knowledge. Connections mediated by Couchsurfing are established as hosts become guests, in certain situations, rotating roles endlessly. According to Camargo (2008, p.7) "[...] hospitality is the basic ritual of human bonding [...]" and the bond in Couchsurfing occurs, among other forms, in this rotation of roles.

Storck has the best host reputation in Jaguarão, which consists of several positive references left by the visitors who stayed at his home. For Cherney (2014), the reputation of a surfer is key to mutual trust, as well as for searching online for a host. On being asked about his main characteristic and what motivates surfers to ask him for lodging, Storck replies that his main feature would be “unprejudiced and nonjudgmental”. Trust is thus built and nurtured from reputation, making future guests want to stay at Storck's house.

In the same vein, the host Fafá, also a student of Production and Cultural Policy, emphasizes that not only living in Jaguarão, but also "living with Uruguayan and Argentinean guests makes learning Spanish a lot easier", and already considers it as her second language.

Couch is very dynamic, has many opportunities. Once, I received a Colombian who did not speak Portuguese well. So, I was curious to learn how to speak Spanish, to open, you know, to be able to receive people better. Since then, I been attending a Spanish language learning group on the Internet so much that I already speak Spanish. This helps a lot with my guests. (Fafá, aged 22, São Paulo State).

These first accounts evinced the different and even antagonistic interests of surfers to join the network. Host Leo, another student interviewed, drew attention to his taste for photographs. He explained the various reasons for his interest in Couchsurfing, namely to make new friendships:

I understand Couchsurfing as a platform of freedom that opens new views of the world [...], and everyday life. It's like talking about photography where every photographer has his lens, you know, his view. I've done my registration because of people who love photography, travel, the unusual, you know? Looking for friendship, too, people that like the same things I like. (Leo, aged 29, Minas Gerais State).

For this host, receiving guests in his home who share similar interests, such as photography, or simply enjoying unusual experiences represents a filter of accep-tability for his "couch", revealing that openness to hospitality may be related to specific interests.

Carlito is a mathematics teacher and shares this conditioned ideal of hospitality. When asked about the process by which he usually browses the site and accepts Couchsurfing requests for hosting he points out:

I read the whole text as much as I can, at least I see the photos and I look if the person is cool and I see if there is anything in common, if the person rides a bicycle, if we share a common interest for riding. I like to cook and I see if the person also likes to cook, well, I see things like that. (Carlito, aged 27, Rio Grande do Sul State).

For this host, the fact that potential guests and he share common interests facilitates the interaction, becoming a requirement for accepting requests and, thus, to receive guests. It is noted here that both Leo and Carlito assume a position that subjects the hospitality in their homes to a rule. This refers to their lifestyles, which involve the taste for photography in the case of Leo (aged 29, Minas Gerais State) and riding and cooking, as far as Carlito (aged 27, Rio Grande do Sul State) is concerned.

As Mauss and Hubert (2005) emphasize, the gift may involve sacrifice and renunciation. Often the one sacrificing gives up daily life interests and activities in order to donate his or her space and time. In the above reports, however, the notion of giving as a form of sacrifice is not, apparently, in Leo and Carlito’s minds. Their lifestyles, tastes, and preferences are a criterion for accepting guests and those who do not share their interests are turned down. Moreover, "the obligation to invite is clearly evident when imposed by clans on clans or tribes on tribes" (Mauss, 1974, p.246).

On the other hand, while surfers have the status “Accepting guests” active in their profiles they choose their guests from acceptability filters, which is not consistent with the values displayed on the website. According to Couchsurfing's vision, it is important to respond to diversity with curiosity, appreciation, and respect.

A young woman studying languages in college, from Manaus, in the State of Amazonas, lives alone and stresses that after talking with colleagues decided to register in the network. According to her, her profile on the website of Couchsurfing is "[...] always active, busy, with many different people requesting lodging." The young woman reveals that she is:

[…] fascinated by everything that concerns traveling, meeting different people and such. I met Couchsurfing here in Rio Grande do Sul. The surprise in each lodging shows a little of one’s universe and how is the outside world. But I would like to travel more, but I cannot afford to go home on vacation, let alone to travel for leisure. So, if I cannot go into the world, I'll make it come to me. (Guru, aged 21, Amazonas State).

As a Couchsurfing host, Guru is looking for new opportunities to travel, expand contacts and perhaps even "get a good job after graduating?" (Guru, aged 21, Amazonas State). In the same vein, guest FlavNav, a 33-year-old woman from Rio Grande do Sul living in Edinburgh, considers the formation of this network as a professional opportunity:

The cool thing about Couchsurfing is not for you to stay for free in someone's house, it's the connection you make, it's meeting people who sometimes work in the same area or in a similar area, right! And that can bear fruit, can generate collaborations in personal and professional life. (Flavnav, aged 33, Rio Grande do Sul State).

Other surfers support the values of Couchsurfing, which aim at sharing experiences, creating connections, as well as tolerance and respect for differences, as already explained. They express these values when they say:

I'm from Bahia, but I live in Jaguarão to study. I’ve always valued a lot to know new cultures and make new friends. Couchsurfing is fantastic, right, and today I can say that I have many friends thanks to it. (Minervina, aged 28, Bahia State).

(...) I believe I can’t run out of Couchsurfing in my life anymore. In it, I have my address book, my friends from all over the world. People who eat meat and people who don’t, who drink and who don’t, who speak English and who don’t, and such. It's amazing how many people have different ways of thinking, languages, different crazes that have in common the taste for traveling. (Bee, aged 24, Rio Grande do Sul State).

In fact, I am from Rio de Janeiro, my mother lives in Rio and I live in Jaguarão with my father, who is an Uruguayan from Rio Branco. I'm from the world. People make contact through the network and when they come in we spend the night talking, so we talk a lot. It's a good opportunity to meet people. (Bird, aged 22, Rio de Janeiro State).

In Couchsurfing, the representation of the threshold seems to be unrelated to the doors, the sofa, the living room, or any other physical room in the house. Considering the surfers' answers about their interest in the network in general, the descriptions related to their life philosophy, motivations, references, and reputation, indicate that the understanding of threshold refers to a "initiation ritual" for the subjects surveyed. The threshold, in this case, begins in a virtual environment in which future hosts request hosting choosing one from several hosts available, in principle, to host them.

In this setting, hosts transpose their thresholds and navigate among surfers, perceive their philosophies and particu-larities as age, civil status, images, and other characteristics. They seek, therefore, to adjust criteria in a movement in which the threshold becomes pendular and swings between choice settings, denial, or acceptance of surfers’ requests for accom-modation. But, what motivates people to travel to Jaguarão, RS, using Couchsurfing?

Tourism and hospitality research tend to study travel motivations as a basis for tourism demand surveys. In 2008, the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) put forward a classification of motivations from the activities carried out during the trips. The motivations for tourism are grouped into eight groups: a) Leisure, recreation, and holidays; b) Visiting friends and relatives; c) Business and professional, including studying; d) Health treatment; e) Religion and Pilgrimages; f) Shopping; g) Visitors in transit and h) Other reasons (OMT, 2008).

From another perspective, Swar-brooke & Horner (2002) and Pearce (2001) committed to reconcile the observable facts, arising from the actions carried out by tourist in a given destination, and the depth of being. Boullón (2004), on the other hand, outlined combined reasons that lead people to travel.

Regarding the surveyed guests, the following statement was reported:

I really like Couchsurfing, to travel, to know other cultures. Wherever I go I take a little of what I learned in India: human dignity. My cousin lives in the city of Melo, Uruguay, so I decided to go through Jaguarão to walk around and get to know a little more about Brazil and also because my cousin ordered some things from the free shop. But I stayed only one night at Couchsurfing, I was just passing through. (Bitmary, aged 26, Mexico)

I don’t have a girlfriend and I’ve always dreamed of knowing Latin America, inspired by the journey of Che Guevara, as in the film. I left my work in Italy and went after my dream. Couchsurfing made the route possible, of course, passing through Jaguarão, Lagoon Mirim and following towards Montevideo and, also, Argentina and Chile. (Teo, aged 31, Italy).

As can be seen from these accounts, there is no single reason for Bitmary and Teo to travel to Jaguarão. They both were in transit, as "visitors in transit" (OMT, 2008; Boullón, 2004). However, when mentioning the infinitive verbs "to walk" and "to know", it is noticed that the surfer was also willing to live other experiences of leisure, and not only "to pass through Jaguarão".

Moreover, it should be noted the mention to duty-free products ordered to Bitmary, also characterizing the motivation of "shopping" (OMT, 2008; Boullón, 2004) for staying in the city. In showing his interest in undertaking the film script of "Motorcycle Diaries", Teo outlines a cultural motivation that can stem from different goals, like fulfilling a dream. Other motivational chara-cteristics arise from the following reports:

It was a surprise because I really did not expect to find someone who had Couchsurfing in Jaguarão and did not expect to find so many people for a city the size of Jaguarão, and located where it is. [...] I had not used in a while and it was cool to connect with the Couchsurfing community. It was only two nights that I spent there, just to go to the seminar to create the cultural policies committee between Brazil and Uruguay. (Flavnav, aged 33, Rio Grande do Sul State).

I went to see Mirim Lagoon. I am from the botanical area, I work in the Biebrza National Park in Poland. In 2009 I went to Lake Titicaca, in the Andes, and there I made friends with gauchos who said that I had to go to Lagoa Mirim. After rese-arching, I realized that it is the second largest lake in South America and I thought, I need to know! I am curious and passionate about the profession. (Pucek, aged 42, Russia).

Flavnav and Pucek have both expresSed interests related to their professions, theater director and tourist guide, respect-tively. Although there is a professional appeal that motivates the "couch surfing" of both guests, it is noted that Pucek presents cultural and educational reasons for traveling to Jaguarão (Boullón, 2004), as if he wanted to enrich his professional performance.

Different motives from those already mentioned were raised by the Mexican woman Potosí. She explained that her friends

[...] went on a motorcycle to Jaguarão, to participate in Motofest, an event that brings together bikers from all over Latin America. I was interested in participating, but not to go by bike from San Luis to Jaguarão (laughs). So, I planned a vacation, I went to Brazil and I took the opportunity to visit other places, like São Paulo and Porto Alegre. And I met the gang in Porto Alegre, and ride to Jaguarão. I like the feeling of freedom and the energy of the wind on the face. And we went to Rio Branco, Lago Merín and Melo, on the Uruguayan side. (Potosí, aged 26, Mexico).

In addition to the previously mentioned classifications, it is worth noting that Potosí also showed mixed motivations that initially concern the interest in "leisure, recreation, or vacations" (OMT, 2008), but also to "know" (Boullón, 2004) and accom-pany friends.

It is important, in this article, to recognize how the surfers’ motivational factor can be influenced by the principles of Couchsurfing and based on the gift. Couchsurfing-mediated hospitality prompts, as a collective premise of usability based on reciprocity, collective motivations for sharing their lives, creating connections, offering kindness wherever one goes, and appre-ciation for differences.

At first, it is noted that Bitmary’s overnight stay in Jaguarão was due to convenience, because even if she was in transit, she would not have requested hosting if she had not to buy products from the duty-free stores to take to her cousin. Teo was on his way through Jaguarão, as he would follow his route to Chile, explaining that he could not do it without Couchsurfing. Pucek has been motivated by a natural element, although his professional curiosity is implicit as well. Flavnav highlighted a professional commitment with intense programming for two days. Finally, Potosí pointed out a specific event to enjoy leisure time with her Mexican friends.

Driven by different reasons, the surfers made no mention to "give, receive, and reciprocate" principles - enunciated by Couchsurfing and the gift theory - when they were asked why they were in Jaguarão. In any case, it is essential to rethink the classi-fications of tourism motivations because they cannot explain the growing fluidity and complexity of the social practices experi-enced in the current context.

2.3 The surfers and in situ arrangement of relationships

The length of stay in the destinations is usually a relevant aspect to be observed when qualifying tourist demand, i.e., tourists. The stay of the surveyed guests was approximately two days. To understand the activities developed by surfers during the time of the guests' stay in Jaguarão, they were asked about the interactions carried out, both inside and outside the house, as well as about situations that have caught their attention.

Hosts’ statements, as well as some guests’, revealed that guests usually had no interest in being guided through the city, although, almost always, they sought to wander the streets alone. Accompanied or not by the host, and even tourist guides, the guests revealed that knowing Jaguarão, its history and its attractions was not a priority.

For Urry (2001, p.16), "there is not a single tourist gaze as such. It varies by society, by social group and by historical period" in which it is inserted. In this research it was possible to perceive that the images posted on Couchsurfing website by the surveyed surfers did not have, as background, known tourist attractions of Jaguarão, RS, such as squares, avenues, churches, architecture, among others.

However, the host Fafá posted images depicting the guest’s stay and the interactions that occurred there in Jaguarão, RS. They are images of "Beco do Papoco” a residence for students that share the rent and other expenses. Fafá, a surveyed host, is the only representative of her student community for the purposes of the research, since she was the only one enrolled in SNS. The image of one of the walls of the house (Figure 2) was presented when she was asked about the activities carried out with the guests.

A tourist generally establishes the first relationship with space through aesthetics, and this is also affected by travelers' perceptions of the images posted on Couchsurfing. This first contact brings sensations and emotions that may arouse interest in interacting more deeply or create distance and dislike for the place.

Fafá emphasized that when she receives a guest, they usually spend the day talking, cooking, and "making art". They talk about music, food, fun, and art. As this hostess points out, at various times they make "art on the walls of ‘Beco’". For her, the messages, drawings, and poems left on the wall by the guests are a good reminder and represent a gift. The maintenance of these records worries the students who live there: "We will have to hand over the house, but how about the walls? Will we have to paint them? This is art and it brings a lot of memories." (Fafá, aged 22, São Paulo State).

The previous account reveals mix feelings, in complex interactions. "Souls are mixed with things and things are mixed with souls. Lives are mixed with each other and just as people and the mixed things leave each of their domains, they mix: that is precisely the contract and exchange” (Mauss, 2003, p.212). And this is reflected in Fafa's concern about the wall, for erasing the records made by those who lived or passed there reveals a break in the cyclical premise of giving, receiving, reciprocating, leaving the residents anxious about it.

This mixture highlighted by Mauss (2003) was also noticed in surfers' reports about how they spend their time and what they do to promote offline interaction:

We started to talk, they slept in the bedroom and in the living room, we would start the conversation at breakfast, make lunch, stay the whole afternoon together, talking about pedals. [...] we made dinner, stayed until dawn drinking, only laughing, laughing, and laughing. (Carlito, aged 27, Rio Grande do Sul State)

You go downtown and walk, so we end up knowing only the town center, for being small too. So, the people who come here, we really want to, ‘let's go there in the river and such”, "let's go to Uruguay", "let's go to the duty-free shops", we want to show both the tourist part of the place and the historical part too, but they do not always want to get out of the house. (Leo, aged 29, Minas Gerais State)

People come here and end up not wanting to leave the house because they are so happy, or even dazzled by it all, with people talking and not only giving that help, but talking and it's very cool, people coming expecting something different from hotel comfort, with all that ‘frou-frou’ and they arrive here, we make a coffee, we prepare a mate, we smoke a cigarette, we talk. (Minervina, aged 28, Bahia State).

From another point of view, comments from Couchsurfing guests refer to the time taken to know a "package" of attractions, as well as the main differences perceived between the trips provided by the network, and the conventional ones. These were called by one of the travelers "tick-the-box tourism”:

[…] most of those who have the means to travel, nowadays, mainly I see it in Brazil, it seems that you have a list, like a to-do list where we cross off items from the list. Even because time is short to know everything, you know, a sort of tick-the-box tourism? (Flavnav, aged 33, Rio Grande do Sul State)

It was not a tourist trip, but a meeting at the border. I was not interested to know, because I think, I believe, that a person with interests will arrive, if the guy has no company and arrives with the backpack, the guy will leave and visit, do a check list and such, and will visit, but I had no interest in the city attractions. (Potosí, aged 24, Mexico)

According to Bauman (1998, p.117), "the people the tourist finds in the place visited are nothing more than accidental meetings, with no future consequences," which contrasts with what was found in this research on a network of travelers in Jaguarão, who said they prioritized the establishment of affective bonds between hosts and guests. About this, another guest says: There are people who think: I will spend one night, with the purpose of sightseeing. I consider myself as a traveler, not as a tourist, there are people coming only to go sightseeing, take selfies and post, that's all. (Pucek, aged 42, Russia)

Meireles (1999) argues that one difference between tourist and traveler is related to what they look for in their trip. For the poetess, while the tourist enjoys material satisfaction (such as taking photos, buying gifts, enjoying hotels), the traveler seeks spiritual experiences related to the contemplation of the trip in general. In Tourism Theories, however, this differentiation lies in the basic answer of the question "What is the reason for your trip?".

The "traditional" tourist, as an invention of modernity (Bey, 1997), seeks the enjoyment of material attractions, as one of the interviewees commented:

[…] I go there because I have to go, because everyone was, right! It's more of this stuff I have to post, I have to show and share my experience than having the experience itself, unlike what Couchsurfing provides (Bitmary, aged 26, Mexico)

On the other hand, travelers seek other pleasures, since they do not use, for example, the whole tourist system available and offered in the destination, such as the infrastructure, the equipment, and the natural and cultural attractions previously classified and disseminated by the media. Travelers seek contemplation, the establishment of bonds with the destination and its inhabitants. Gomes et al. (2007) emphasize that tourism should be envisaged as a human and social experience. In this sense, tourism itself can consist of trips in search of recognition of the other and oneself, previously unknown and far away. The places are "centers of value" and provide experiences, means of knowledge, and construction of reality.

Other interviewees, both hosts and guests, focused on the border and on their most significant tourist attractions when referring to the daily routine, and to their activities during their stay in the hosts' homes.

We always stopped and gazed at the landscape, and for me, the first thing when I arrived in the city was to go to Ponte Mauá. I thought, "Wow, this is very different," because it was an extreme heat and it was a really cool feeling to be in a place that, on the other side, is in fact a totally different country, a totally different culture and standing there with the passing river is a somewhat bucolic thing too. (Teo, aged 31, Italy)

Jaguarão is a very historic city, has beautiful buildings and cool historical points, we ended up taking the guests to know these places, meet some people, some events like this and they loved it, they were delighted with the military ward, the bridge, the churches, and it is very cool. (Guru, aged 21, Amazonas State)

When I am asked, I show the 15 November Street, which is known as the most artistic street, and then the Minervina Correia church, the matriz church, the military ward, the architecture of the bridge seen from below and from above, the central market that is undergoing renovation, the Escravos square, the Bandeiras square, the squares are more like that, these main points, the regent, the theater Esperança. (Fafá, aged 22, São Paulo State)

I think it was summer and then they said that after a while they were watching the sunset there on the Uruguay side, where there are those benches, behind the duty-free shops, facing the river, they stayed there. (Bird, aged 22, Rio de Janeiro State)

As can be seen in these reports, in the context of a virtual network of travelers such as Couchsurfing in Jaguarão, leisure experiences are fundamental for hospitality, as they allow for exchanges between surfers, hosts and guests. Another aspect to be highlighted is that the triad "give, receive and reciprocate" is present in the statements of most of the interviewees who, from the contact established through the SNS, value reciprocity. In the virtual paradigm, the threshold is crossed with the “turning of the key”, when moving from offline to online, inserting login and password in SNS Couchsurfing, surfing or "appearing at the doors" and "houses" (profiles) of other surfers.

Mauss (2003) looked at the symbolism gift exchange between the Andaman peoples who are considered very hospitable. Among them, there is a playful way of welcoming, besides voluntary retribution, although obligatory (Mauss, 2003). This example can be related to the study presented here, under the premise that the Couchsurfing can be an exchange stemming from hospitality, with connotations that refer to the collective when the trips are based on the exchanges and generosity.

These findings are apparent in offline interactions between guests and hosts, in which, in the studied context, stand out the offerings of food, maté drinking, boiled dinners, as gifts that complement the hosting donated by the hosts. On the other hand, the guests, in certain moments, received, and tried to return the hospitality during their stay in the residence, as "gesture of compensation" (Grassi, 2011, p.45). This was commented on by a guest:

She was always in the kitchen. She is from São Paulo and has other residents in the ‘Beco’, from other places. They bought meat for the barbecue. I happen to be a vegetarian and they soon went back to the market to get vegetables, they were very understanding and receptive. I went with them and bought the drink. (Potosí, aged 26, Mexico)

The "gift" initiative and the generosity implicit in this gesture lead to the obligation of retribution which, although related to the donor's morality, is identified by Mauss (2003) as an advantage, an economic interest. In this sense, Mauss (2003) makes a few observations that go against arguments about human motivations because they are beyond morality. As the author argues, morality may be different from one society to another, but it meets the symbolic threefold obligation of giving, receiving, and reciprocating.

As already mentioned, even if some experiences are described as negative, Couchsurfing members abstain from judging to continue in the experience, valuing a system of reciprocity of interpersonal character. Potosí complements:

[…] I really came out feeling like I made friends there, people that even if we do not talk often, now I know they're there and they know I'm here, so something good can come at some point, right? It may happen that someday one of them will come to Mexico. I called them to stay in my house. (Potosí, aged 26, Mexico)

On the other hand, not all exchanges are equal. The statement below has caught our attention:

And when my host realized I had many bottles of wine and free shops bags, he soon came to ask for financial help to help with his water and electricity bills. I was amazed, it never occurred to me. (Bitmary, aged 26, Mexico)

The exchanges arising from relations between surfers express a variety of symbolism. At the same time, they assume an internal, affective character, based on feelings of friendship and generosity, but also reveal the inexistence of a sacrifice for them to occur. For Camargo (2006), hospitality is given to the approach of spaces and people. The moment this hospitality abolishes the sacrifice implicit in its practices, then it is not hospitality inspired by the gift. It is a "staged" hospitality, as Gotman (2001) recalls.

An example of this was the request for "financial collaboration" from Bitmary’s host, on the grounds of contributing to the expenses of the house. According to the statement, the guest ended up assuming a contract in which there is merely an exchange and, according to Camargo (2006), conflicts with the principle of hospitality.

Gotman (2009) explains the asymmetrical relationship of free hospitality as an aspect engendered by the gift. On the one hand, monetary exchange, as in the commercial lodging contracts, interferes with this asymmetry of hospitality. In the case of Bitmary, the payment for the hospitality in Jaguarão, according to her, cost R$ 40.00, left her on an equal footing with her host, mischaracterizing the conduct suggested by the website "Don’t charge for your couch."

Hosts are autonomous inside their homes, since in terms of territory they are in a position superior to the guest (Gotman, 2009). From the moment there is a monetary relationship, determined by the financial payment for the use of space and even by the social relations and interactions existing inside the residence, there is a propensity for the symmetry of hospitality, as it happens in hotels. This symmetry evokes a position of equality between host and guest in the home environment, unlike hospitality based on the gift.

3 FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

This article sought to identify and discuss the main interests and motivations for Couchsurfing network trips, among hosts and guests in Jagurão, as well as to understand the system of exchanges between both. This discussion draws on the studies of hospitality based on Marcel Mauss's Theory of the Gift.

From the studies of Mauss (2003), it is inferred that the exchange, in the context of the research on hospitality in Jaguarão mediated by Couchsurfing, is initiated from the moment in which a profile is chosen and the request is made to stay hosted, i.e., still online. From this, a commitment is made to the mutual gift, arising from hosts and guests’ conscience or moral obligation to give, receive and reciprocate hospitality. At the border of these interrelations is the virtual border between hosts and guests in the extreme south of Brazil.

On these surfers’ motivations for Couchsurfing in Jaguarão, the research found that these are varied. The trips have the purpose of duty-free shopping, visiting relatives, developing professional interests, even enjoying leisure during vacation periods. Arguably, the guests did not mention collective interests referenced by the triad "give, receive and reciprocate" implicit in the principles of Couchsurfing. This was pointed out in other works as a quality of the members of this SNS, as stated by authors such as Bialski (2007) and Figueiredo (2008), for example.

Among the systems of exchange analyzed an episode was observed involving monetary exchange along the lines of commercial hospitality. Revealed by the comment of a host, the asymmetry of hospitality equates the same conditions of belongingness of the space inside the houses, between guest and host. This asymmetrical feature enhances the contractual character of hospitality (Camargo, 2006), but does not present a characteristic of the SNS analyzed.

On the other hand, hosts' offerings of food, outings, and drinking maté as gifts that went beyond simple lodging were often compensated by immediate retribution from the guests. Some of them bought drinks for dinner and left poems, souvenirs, and drawings in the houses, characterizing the symbolic exchange based on the threefold obligation to give, receive, and reciprocate (Mauss, 2003).

It is essential to add that, unlike a growing number of studies on tourist demand, this research focused both on hosts and guests and pointed out a peculiarity of Jaguarão regarding the first group. Just as with guests, Jaguarão hosts make up a floating local population, made up of UNIPAMPA students. The social practices of Couchsurfing in Jaguarão allowed the understanding of hospitality and exchanges based on Marcel Mauss's theory, based on the profiles and characteristics of the surfers surveyed, most of them coming from outside the municipality (and the state of Rio Grande do Sul).

The SNSs, allied to the flow of current information at their core, configure the modus vivendi of contemporary society. However, it becomes imperative new empirical instrumentalizations under different circumstances consistent with the liquidity of rising social practices, both in terms of Leisure and Tourism and Hospitality.

texto em

texto em