1 INTRODUCTION

Sport tourism connects two separate but increasingly important areas of socio-economic development: one of the largest economic sectors in the world (tourism) and one of the most globally influential activities (sport events and activities) (Peeters, Matheson & Szymanski, 2014). This form of tourism in particular has received international attention and participation because of the organization of mega-events as strategic for place branding with sports as a channel of public diplomacy (Anholt, 2007; Govers & Go, 2009; Lee, 2010; Fola, 2011; Bodet & Lacassagne, 2012). Sport event tourism has therefore become an important subset of both the tourism market and is advantageous for destinations of sport tourism (Standeven & de Knop, 1999; Smith & Stevenson, 2009; Henderson, Foo, Lim & Yip, 2010). Whereas tourists can be motivated to attend sport events as participants (Kaplanidou & Vogt, 2007), a larger number of these sport tourists are event spectators (Comperio Research, 2009).

Apart from domestic sport event tourists or participants in regular local community sport competitions, some mega- or specific sport events have the capacity to attract large-scale international tourist groups (WTO, 2002). The Olympic Games and several other major sport events are the ones that typically draw the attention and interest of international sport spectators, fans, and tourists. In conjunction with these large-scale events, some professional sport teams and leagues of specific types of sports (e.g., soccer, basketball, tennis and car racing, etc.) have been actively expanding their markets overseas through various forms of promotion such as international game broadcasts, team merchandising, and product and brand extensions (Smith & Stevenson, 2009; Bodet & Lacassagne, 2012; George, Swart & Jenkins, 2013). Watching sport games or visiting sport facilities has become an increasingly popular agenda in a tourist travel itinerary, demonstrating a different motivation and experiential meaning from more traditional event participants (Kaplanidou & Vogt, 2007). This paper focuses specifically on the spectator group of sport event tourists.

Hong Kong is an Asian metropolis which currently hosts a wide variety of sport events and activities (e.g., Hong Kong Tennis Open Event Management Limited, 2016; HKTB, 2016). However, the domestic market for local sport events appeared to be very small. In the 2015-16 season of Hong Kong Premier League of soccer, for instance, the average number of spectators was only about 950, and the stadiums were filled to below 50% of possible capacity (Hong Kong Football Association, n.d.). In global sport events like the Olympics, Hong Kong competes with its own team representing the population. Events such as these have encompassed a series of other tourist activities periodically and thus can be classified as one of the travel motivations of both inbound and outgoing visitors. However, there is no clear understanding of how local Hong Kong residents respond to the global sport tourism trend as outbound sport event tourists.

The Hong Kong Government does not regularly survey outbound tourists (except for a statistical report in 2003, which indicated that a small percentage of Hong Kong residents took long-haul travel for sport activities such as golf and aquatic events (4.2%), and others forms of sports, e.g., ice-skating and ballgames (3.0%) (HKCSD, 2003). However, these active forms of participation in sport activity did not represent a substantial portion of more passive forms of activities such as sport event attendance. There is neither information about the state of this form of outbound tourism nor has there been systematic research on the motivation and determinants of this growing field of sport event tourism in Hong Kong.

Brazil, on the other hand, is a popular sport event destination, having recently hosted two international mega sport events: the FIFA World Cup in 2014 and the Olympics in 2016 (Toohey & Veal, 2007; Muresherwa, Swart & Daniels, 2015; Uvinha, 2016; Rocha & Fink, 2017). Brazil has successfully hosted several major sport events in the span of just one decade (2007-2016), including the Pan American Games Rio 2007, Parapan American Games Rio 2007, 5th CISM Military World Games 2011, FIFA Confederations Cup 2013, FIFA World Cup 2014, Olympic Games Rio 2016, and Paralympic Games Rio 2016. It has been estimated that this expansion in hosting of athletic events has had a huge impact in more than fifty sectors, including those related to leisure and tourism, and generating an impressive effect in terms of infrastructure, creation of jobs, income, and promotion of Brazil´s image on a global scale as a tourist destination. The 2016 Summer Olympics in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, was an event held for the first time in South America and which offered many challenges in terms of management. Soccer as an Olympic modality was not just limited to Rio, but was also hosted in five other Brazilian cities, including São Paulo (the largest city in Brazil and its financial center). As such, São Paulo is the selected city in Brazil for the focus of this study.

There is no specific connection between the sport events of Brazil and Hong Kong, either in the public or the private sector. It can be postulated that Brazil’s sport infrastructure, tradition, and culture tend to foster a stronger potential market of sport event tourists than a typical urban destination like Hong Kong. However, it is necessary to further understand where the respective differences lie, and what determines an interest in participating in sporting event tourism in each area. It is therefore valuable to study the residents from these two places in terms of their similarities and differences in travel incentive, tourist characteristics, and the factors affecting their sport event travel. These attributes will provide important information for the worldwide Destination Marketing Organizations (DMOs) to design suitable tourism products to attract customers from this market segment.

This apparent knowledge gap therefore stimulates an empirical study, using Hong Kong and Brazil as two comparative cases, to provide answers to the following questions:

What is the level of incentive of the potential sport event tourist?

What are the travel characteristics of sport event tourists?

What are the key determinants affecting the incentive level for sport event tourism?

The answers to the research questions may largely reflect the willingness to travel and the consideration of residents for outbound sport event travel in the two regions. The travel motivation, ability and market characteristics may be very different between Hong Kong and Brazilian city residents. Such disparity may nevertheless allow destination marketers to create tourist products in the short term, and decision-makers to develop sport tourist attractions and nurture an atmosphere for sport culture in the long term.

Moreover, one of the purposes of this research is to verify whether the popularity of sport event tourism among Hong Kong outbound travellers matches with the global trend, or how this differs from the Brazilian market. The findings also provide data to assess the market potential of this form of tourism in Hong Kong, which may yield useful information and recommendations for market segmentation, product development and more importantly, relevant strategy and policy that may foster a domestic sport event tourism attracting local customers. The outcome of the study augments the market information about characteristics of a sport event that can attract the greater interest of sport tourists.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

Sport tourism is widely defined as tourist travel to destinations for the primary purpose of participating in sport activities or related events (Standeven & de Knop, 1999). The definition of sport tourism showed a product-experience dichotomy based on tourism scholars’ divergent interpretations. Similar to many other forms of tourism, sport tourism is regarded as an industry embracing a series of attractions, products, and services such as accommodation, stadia, sport event ticketing, sport team businesses and transportation (Hay, 1989; Weed & Bull, 2009). Kurtzman and Zauhar (1997), for example, sought to describe sport tourism through the categorization of five main products, namely attractions, tours, cruises, resorts, and events. These notions of sport tourism were sectoral, and thus augmented the criticism that it ignored a destination’s human or tourist dimensions (Standevan, 1998).

The attributes of sport tourism should reflect the distinctive and synergetic phenomenon of the nature of sport activities (Standevan, 1998). Sport tourism is also considered to be a cultural experience, which consists of the interaction of place, activity, and people that shape the overall tourists’ experience (Weed, 2008). As a result, a sport tourism experience must be unique rather than merely the mixture of sport and tourism (Weed, 2005).

Currently, there are three main types of behaviour associated with sport tourism, firstly, active sport tourism, where travellers actively participate in a particular type of non-event-based or unorganized sport activity, such as taking “club” holidays for land-based games like golf or tennis, or watersports such as swimming, sailing, windsurfing, etc. (de Knop, 1990). The second type is sport event tourism during which travelers spectate different kinds of sport events like the Olympic Games, the FIFA World Cup, national ballgame championships, and regional or local events. The essence of this subset of sport tourism is the “being there” experience which differs from experiencing the event when shown on television or the Internet. The impact of the large-scale events and the spectators has received researchers’ attention since the 1980s (Ritchie & Aitken, 1984) and has continued (Berkowitz, Gjermano, Gomez, & Schafer, 2007; Zhang & Zhao, 2009). Lastly, a relatively minor area of sport tourism is nostalgia sport tourism where the host sites of mega-events became tourist attractions, though this research area has not been well-studied.

These three types of sport tourism can be given a more refined definition: leisure-based travel that draws visitors temporarily from their homes to participate in physical sport activities, to watch these activities, or to sight-see at the destinations associated with sport activities (Gibson, 1998). Sport event tourism is one of the subsets in sport tourism characterized by the existence of organized sport activities available for inbound participants or speculators.

2.1 Sport events: Global to domestic markets

The characteristics of sport event tourists depend on the respective type of sport events in question, and the form of engagement by the tourists; they can be either active event tourists (i.e., players or participants) or passive event tourists (as spectators onsite) including a niche segment of watching friends and relatives in the events (Scott & Turco, 2007).

Passive forms of sport events can be classified into two groups, namely “yearly events” and “infrequent events”. Yearly events are literally those which allow audiences to watch the events on an annual basis, and which include seasonal leagues and cup competitions such as the National Basketball Association (NBA), Formula 1, UEFA Champions League, and Premier League. Infrequent events are defined as events hosted every other year or more than one year each time, which are mainly mega-events such as the Olympic Games and the World Cup.

Destinations ranging from national, regional, and community levels have begun to realize the huge economic return generated from sport events and their tourism markets (Turco, 1998; Higham, 1999; Dimmock & Tiyce, 2001; Toohey & Veal, 2007; Gratton & Preuss, 2008; Alexandris & Kaplanidou, 2014), although negative socio-cultural and security impacts were also shown to eventually affect tourist travel (Armstrong & Giulianotti, 2001; Diaz, 2001; Kennelly, 2005; Toohey & Taylor, 2005; Solberg & Preuss, 2007). According to Schumacher (2012), however, sport event tourism had a significant and fast growth in the United States between 2010 and 2012 when inbound tourists’ arrival for attending sport events reached almost 24 million, with tourists spending US$7.68 billion in 2011. In some cases, yearly sport events have become the earmarked tourism activities of a city (e.g., the Formula 1 racing, see Henderson et al., 2010). Due to the effects of globalization and the as yet untapped market and tourism potential there, the concept of increasing the number of sport events to be held in Asian countries is being explored as part of tourism planning (Okayasu, Nogawa & Morais, 2010).

However, the impact of yearly or frequent events was less substantial than when compared with a sports mega-event. Very often, these mega-events are treated as part of a branding strategy for the respective country (e.g., Anholt, 2007). In 2010, for instance, South Africa hosted the World Cup, and attracted a total of about 360,000 domestic and foreign tourists (Knott, Allen & Swart, 2012) though the actual number of tourist arrivals did not reach original expectations (Briedenhann, 2011; Peeters et al., 2014). Foreign tourists comprised 176,000 people from participant countries and 46,000 people from non-participant nations (FIFA, n.d.). This example of the 2010 World Cup illustrates that, firstly, sports mega-events might only attract a finite number of tourists, although the number could still be considerable. Secondly, being supporters of a team or participating territories are two important factors encouraging people to engage in sport events. Similar but greater impacts were observed during the Olympic Games, where many host countries considered the events to be an important improvement in visibility, marketing, and branding opportunities for their country’s image (Berkowitz et al., 2007; Zhang & Zhao, 2009; Florek & Insch, 2011). These sport events allowed countries to present the diversified facets of their tourist destinations, such as natural features and cultural diversity, to the world on a larger global platform (Knott, Allen & Swart, 2012).

The influences of sport events can arguably be long-lasting (Gratton & Preuss, 2008), especially when a well-integrated infrastructure with the physical venue, accommodation facilities and efficient transport “can reduce costs, improve spectator and athlete convenience and provide long-term benefits for the community after the event has gone” (Smith, 2006, p. 23). According to Solberg and Preuss (2007), the infrastructure development brought by sport events can be divided into two sections: the hard (primary structures such as sports and leisure facilities; secondary structures such as housing and recreation provisions; and tertiary structures (work and traffic changes) and soft infrastructure changes. The physical or hard infrastructure invested in prior to the events might have an extended influence, such as a living memorial that preserves symbols of visible memories of the events for local people and visitors in the future (Girginov & Hills, 2008; Grix & Carmichael, 2012). The soft infrastructure, in a parallel sense, refers to the knowledge and skill enhancement of residents due to the sport event experience (Maunsell, 2004). Aspects of soft infrastructure development might be related to hospitality training for volunteers, an upgrade of the skills in the service industry, the ability to compete for more international events, and the safety know-how of organizing large-scale events, which eventually become human capital of the host territory (Hall, 2006; Solberg & Preuss, 2007; Lockstone & Baum, 2008).

Apart from global or national-scale mega-events, researchers also discovered that some local or community-level sport events carry the potential to attract visitors and generate business opportunities (Gibson, Willming & Holdnak, 2003). These visitors were mainly residents from local districts with a high proximity to the sport venues, and could foster the growth of the market of sport domestic tourism. The Travel Industry Association of America (2003) recorded that over 50 million United States residents travel 50 miles or more away to attend sport events. The accumulated impact of these activities should not be ignored, especially since residents may become a future outbound market as sport event tourists.

The study of domestic sport tourism by Gibson et al. (2003) indicated clearly the influence of “being a fan” and a “sense of belonging” to the event, which attendance can extend beyond geographical boundaries. Despite the relationship between team performance and audience behaviour (Young, 2002; Delaney & Madigan, 2009), most importantly, Gibson’s study revealed that (1) small scale and seasonal sport events have the capability to attract tourists, (2) certain groups of tourists tend to consider watching sport events as part of their itinerary, (3) most sport teams, regardless of the nature or geographical scale, usually have a consolidated groups of fan being potential but active sport event tourists. The larger the sport team, the higher the potential to form a larger group of sport tourists.

The marketing of sport event tourism focused on the economic return of the event period, but there are also supporters of the sustaining effect on post-event tourism and long-term sport participation (Turco, 1998; Girginov & Hills, 2008; Grix, Brannagan & Houlihan, 2015) because the economic impact of the sport events on sport service providers and destination marketers may become the deciding factor in future resource allocation decisions (Higham, 1999; Dimmock & Tiyce, 2001; Hall, 2006; Müller, 2012, 2014).

2.2 Determinants to the incentives of sport event tourism

Sport event tourism is an emerging and more vulnerable form of tourism (Henderson et al., 2010) that requires different strategies to increase the travel incentives of potential travellers. More specifically, these strategies aim to influence behavioural intentions by creating positive event image and visitor satisfaction (Alexandris & Kaplanidou, 2014; Koo, Byon, & Baker, 2014). As Funk, Toohey and Bruun (2007) suggested, prior sport involvement and travel benefits pushed tourists to participate in the sport events, while offering them an escape from daily life, opportunities for social interaction, time to relax, knowledge exploration and cultural learning. These are the motivations behind sport event tourism, but the focus of this study is more about the external environment and sport-related settings as incentive determination.

Other than watching the games or events, tourists could have interest in attractions related to their favourite clubs or teams, or be interested in more information about the events (Gibson et al., 2003; Xing & Chalip, 2006, 2009) because there could be other tourist attractions available in the vicinity of a sport event venue. These attractions may become another factor affecting sport event tourists who often have other travel purposes beyond sport events themselves (Gibson et al., 2003). Together with the provision of transportation infrastructure and services, these attractions, and facilities all shape the overall tourist experience (MacKay & Crompton, 1988; Prideaux, 2000; Schiefelbusch, Jain, Schäfer & Müller, 2007; Briedenhann, 2011) and affect the intention to return to a sport destination (Shonk & Chelladurai, 2008). The identity of being a fan of a sport team or club exerts much influence in pushing sport event tourists to travel, as proved by researchers over many years (e.g., McCra-cken, 1989; Wann, 1995; Gibson et al., 2003; Mahony, Madrigal & Howard, 2000; Florek, Breitbarth & Conejo, 2008; Xing & Chalip, 2006, 2009; Briedenhann, 2011; Peeters et al., 2014). Some powerful professional leagues attempted to improve their influences by expanding their team recognition and brands through the sale of broadcast rights, team merchandise, and other product extensions overseas (Fay, 2003). There were also some systematic, cultural, and financial barriers to travel that are applicable to typical or sport tourists (Kim, Guo, & Agrusa, 2005). These physical or tangible aspects constitute the cognitive image of a sport destination, which in turn influences the incentives of sport event tourists (Funk et al., 2007). A summary of the sources of the determinants to sport event tourism incentives is provided in Table 1.

Table 1 Factors affecting tourists’ incentives to participate in sport event tourism

| Factor | Indicators | Sources of reference |

| Attractiveness of sport event | • Excitement about sport event |

Shonk & Chelladurai (2008); Henderson et al. (2010); Briedenhann (2011); Peeters et al. (2014) |

| • Existence of additional tourist activities related to sport event or team | Neirotti, Bosetti & Teed (2001); Gibson et al. (2003); Xing & Chalip (2009); Henderson et al. (2010); Alexandris & Kaplanidou, (2014); Koo et al. (2014) |

|

| Travel experience | • Number of tourist attractions • Availability of transportation infrastructure and services • Quality of accommodations • Safety • Attitude of local residents at destination |

Prideaux (2000); Schiefelbusch et al. (2007); Shonk & Chelladurai (2008); Okayasu et al. (2010); Briedenhann (2011); Korstanje, Tzanelli & Clayton (2014); Rocha & Fink (2017) |

| Identity of being a fan | • Identity of a fan of sport team or club • Identity of a fan at sport event |

Czepiel & Gilmore (1987); Branscombe & Wann (1994); Wann (1995); Faulkner, Tideswell, & Weston (1998); Mahony, Madrigal & Howard (2000); Gibson et al. (2003); Florek, Breitbarth & Conejo (2008); Xing & Chalip (2009); Briedenhann (2011); Alexandris & Kaplanidou, (2014); Koo et al. (2014); Peeters et al. (2014) |

| Travel cost | • Cost of sport event admission • Cost of travel • Exchange rate |

Kim et al. (2005); van Cranenburgh, Chorus, & van Wee (2014) |

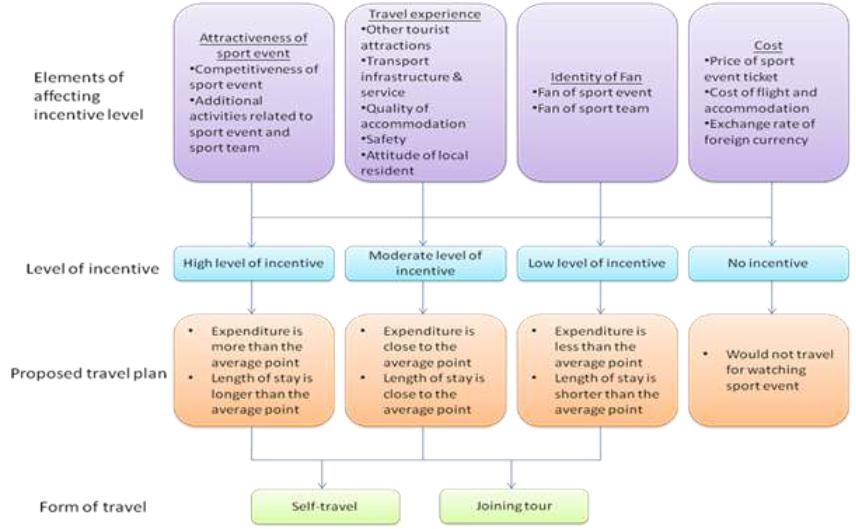

These determinants tend to derive different levels of incentives to sport event tourism and therefore may result in a different set of travel characteristics from potential outbound tourists from different tourist-generating origins or territories. Based on the collation of the abovementioned incentive determinants, the travel decision-making process of a typical sport event tourist is illustrated in Figure 1.

A recent study on American travellers in Brazil suggested that a well-established territory-wide (city or country) tourism and hospitality infrastructure has a positive association with the duration of stay by tourists (Rocha & Fink, 2017). The study, nevertheless, discovered a weaker influence on tourism by the 2016 Rio Olympic Games, which indicated a detached connection between the Games and tourism benefit. Safety is a key determinant to the interest in travelling to Brazil for sport events and other tourist activities.

2.3 Travel characteristics of sport event tourists

Based on different levels of travel incentives and the determinants, potential sport event tourists may show a range of travel characteristics from high-incentive, moderate-incentive, low-incentive to no-incentive groups, rather than a single or a fixed pattern of travel. These travel characteristics are measured by, for example, trip duration and spending. In general, travellers with a high-incentive level tend to stay longer and spend more for tourism activities.

Regarding travel characteristics, the average duration and the average expenditure of a typical leisure trip can be found in some reports of travel websites. This information can be used as a general reference point for comparison between the sport event market and that of typical leisure trips. In the surveys conducted by two popular travel service online suppliers, Hotels.com (2015) and Travelzoo (2016), for example, the most popular countries for Hong Kong residents as tourists were Asian countries, including Taiwan, Ja-

pan, South Korea, and Thailand, while the top-ranked European countries were the United Kingdom and France. An international statistical report on tourism indicated that the average duration of a trip to the above countries was about a week (6 days for South Korea; 8 days for Taiwan or Thailand; 9 days for Japan; 8 days for both the United Kingdom and France). Moreover, the average spending on each trip by Hong Kong residents was HK$13,412 or about US$1,719 in 2014 (MasterCard, 2015).

3 METHODOLOGY

A cross-sectional approach was adopted to collect the responses at a single point of time, as it could reflect the current phenomenon of a large group of respondents, whereas the data was assessed to verify the presence of any inter-group variation at a given time (Henn, Weinstein & Foard, 2009). This study utilized two separate questionnaire-based surveys to collect responses from Hong Kong and Brazil. In both territories, the surveys were self-administered or onsite to include residents from several selected locations. Due to language differences, the same set of questionnaires was translated into two bilingual (Chinese-English in Hong Kong and Portuguese-English in Brazil) versions. A pilot study using an English version was conducted beforehand among 30 postgraduate students in Hong Kong to test the reliability and validity of the questions and the language. Further examination of the questions was also performed among researchers on both sides. No major amendment was required before the main survey.

The questionnaire in this study consisted of three main parts: (1) demographic and socio-economic information, personal travel characteristics of the respondents; (2) questions measuring the variables of interest, perception and preference of sport event travel; (3) the level of importance in sport event tourism aspects, preference of activities and tourist attractions, other requirements or identifying as a fan of any sport event or team. Details of design and structure of the questionnaire are presented in Appendix 1.

3.1 Sampling and data collection

The sampling and data collection process basically follows the practice of local resident survey by Akis, Peristianis, and Warner (1996). Since residents aged 18 or above are the target population in Hong Kong, an onsite survey was considered to be a more accurate and objective method of data collection (Tasci & Gartner, 2007). Cluster random sampling was applied (Black, 1999) in three selected districts that represent a population with median household income and of median age in Hong Kong (CSD, 2015). A series of surveys were conducted in May 2016, on two randomly selected main streets in each district. After a brief introduction of the research purpose, the questionnaires were distributed to the respondents. The survey was voluntary and self-administered, but the trained researcher would facilitate the respondents when questions arose. The respondents normally took about 10 minutes to complete a questionnaire. A total of 150 questionnaires were distributed, and 134 yielded completed responses, contributing to a response rate of 89%.

The field survey in Brazil was conducted with local Brazilian residents randomly between November and December 2016 by cluster random sampling on different locations in São Paulo. Similarly, the survey was voluntary and self-administered, and took about 10 minutes each. In this part, a total of 152 questionnaires were distributed and 151 completed responses were collected, reaching a high response rate of 99%. These respondents came from mainly São Paulo and its peripheral area (over 80%), other parts in Brazil such as Rio de Janeiro (10%), and the remaining 10% were from other cities.

3.2 Methods of data analysis

Due to the different nature and sources of data, this study used a parallel comparison between samples from Hong Kong and Brazil, which followed many other tourism studies in a variety of geographical settings (Stepchenkova & Mills, 2010). This study applied two key methods of data analysis for the datasets. Firstly, a matrix analysis shows the mean scores of the respondent group with an independent sample t-test to verify inter-group differences. Secondly, multiple linear regression (MLR) is designed to identify the determinants of sport event tourism aspects that significantly influence the overall interest in this tourism form in both territories. The IBM Statistical Package for Social Sciences 23.0 was the software platform used in the operation. To verify the dataset quality of the model variables, reliability tests using Cronbach’s alpha were performed. The results showed the Cronbach’s alpha of 0.729 and 0.729 in the data of Hong Kong and Brazil respectively, indicating high levels of data reliability for all subsequent analyses (Kline, 2000).

4 RESULTS

The socio-demographic profile and the visitation characteristics of the respondent groups are presented in Appendix 2. Both Hong Kong and Brazilian samples have a balanced gender distribution (the gender difference does not exceed 10%). A majority of the sample is within the age range of 18 to 39 years old (about 70% to 86%), they are mostly well-educated with a tertiary education (77-88%), they have relatively lower personal income (about 80% have a monthly salary of US$3,000 or below), and mostly they are either employed or are students. The two groups have divergent levels of travel experience. Very differently, most Brazilian respondents attended the Rio Olympics, while almost no Hong Kong respondents attended. Less than 10% of Hong Kong respondents have no outbound travel experience but about 38% from Brazil have not travelled before. Furthermore, a majority of Brazilian respondents are fans of any sporting event (60%) and team (68%), which is higher than the results of the Hong Kong group (55% are fans of any event and 47% are fans of any team).

As shown in Table 2, Brazilian respondents are more willing to stay longer (over 12 nights) for sport event tourism (about 17-22%) than Hong Kong respondents (about 6-15%) at the same duration, excluding the “not applicable” respondents who did not show any interest in watching an event. Brazilian respondents are much more interested in watching both yearly and infrequent sport events as both the number of events mentioned and the types of events are doubled when compared with Hong Kong respondents. This shows that Brazilians have an interest in a greater diversity of events than the Hong Kong audience. Their expected average amount of spending is also higher than that of Hong Kong people. About 17-31% of Brazilian respondents are willing to offer a budget of over US$2,000 for a sport event trip, as compared with only about 14-22% for the Hong Kong group.

Table 2 Travel characteristics of sport event trips by Hong Kong and Brazilian respondents

| Hong Kong (n = 134) | Brazil (n = 151) | |||

| Interested in watching on site | Yearly events | Infrequent events | Yearly events | Infrequent events |

| 69 entries, 15 types | 66 entries, 3 types | 123 entries, 35 types | 116 entries, 7 types | |

| Trip duration (night(s)) | Yearly events | Infrequent events | Yearly events | Infrequent events |

| 0-2 | 3 (2.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 15 (9.9%) | 10 (6.6%) |

| 3-5 | 18 (13.4%) | 10 (7.5%) | 28 (18.5%) | 25 (16.6%) |

| 6-8 | 24 (17.9%) | 25 (18.7%) | 17 (11.3%) | 32 (21.2%) |

| 9-11 | 16 (11.9%) | 11 (8.2%) | 2 (1.3%) | 15 (9.9%) |

| 12-14 | 3 (2.2%) | 16 (11.9%) | 19 (12.6%) | 14 (9.3%) |

| Over 14 | 5 (3.7%) | 4 (3.0%) | 7 (4.6%) | 20 (13.2%) |

| Not applicable | 65 (48.5%) | 68 (50.7%) | 63 (41.7%) | 35 (23.2%) |

| Total | 134 (100%) | 134 (100%) | 151 (100%) | 151 (100%) |

| Budget (US$) | Yearly events | Infrequent events | Yearly events | Infrequent events |

| Below $500 | 3 (2.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 16 (10.6%) | 20 (13.2%) |

| $501-1,000 | 14 (10.4%) | 7 (5.2%) | 13 (8.6%) | 15 (9.9%) |

| $1,001-1,500 | 13 (9.7%) | 12 (9.0%) | 18 (11.9%) | 15 (9.9%) |

| $1,501-2,000 | 20 (14.9%) | 17 (12.7%) | 15 (9.9%) | 19 (12.6%) |

| $2,001-2,500 | 14 (10.4%) | 16 (11.9%) | 9 (6.0%) | 20 (13.2%) |

| Over $2,500 | 5 (3.7%) | 14 (10.4%) | 17 (11.3%) | 27 (17.9%) |

| Not applicable | 65 (48.5%) | 68 (50.7%) | 63 (41.7%) | 35 (23.2%) |

| Total | 134 (100%) | 134 (100%) | 151 (100%) | 151 (100%) |

4.1 Inter-group comparison in sport event tourism preferences and determinants

The ratings of sport event tourism perception by respondents are presented in Table 3. Through value comparison by an independent-sample t-test, the findings revealed that the respondents from Brazil possess significantly stronger interests in yearly and infrequent sport event tourism, a greater preference to participate in package tours, but a stronger feeling of being limited by expensive event ticket pricing and travel costs than Hong Kong residents. On the contrary, Hong Kong residents consider a significantly lower exchange rate of currency for travel than Brazilian respondents. The Rio Olympics has led to a positive effect on encouraging people’s interest in sport event travel, although such effect is not significantly different between the territories.

Regarding the level of importance in the aspects of sport event tourism, respondents from Brazil again show significantly higher values for most items, except excite-

ment about sport event and attitude of local people at destination, both without significant difference. Comparing the rankings, safety is the paramount concern about sport event travel for both respondent groups. Whereas the availability of other tourist attractions is another important aspect, Hong Kong respondents focus on the exciting nature of a specific event, while people from Brazil are more concerned with transportation provisions during travel. Accommodations and any additional sport-related activities are among the lowest-valued aspects for both groups.

Table 3 Ratings of sport event tourism aspects by Hong Kong and Brazilian respondents

| Hong Kong (n = 134) | Brazil (n = 151) | |||

| Mean [Rank] | S.D. | Mean [Rank] | S.D. | |

| Perception of sport event tourism | ||||

| I want to travel for watching a yearly sport event. | 3.43 | 1.968 | 4.17** | 2.071 |

| I want to travel for watching an infrequent sport event. | 3.49 | 1.814 | 5.30** | 1.792 |

| If I travel for watching a sport event, I choose to join a package tour instead of self-travel. | 2.45 | 1.352 | 2.99** | 1.842 |

| The ticket price of sport events is generally high. | 4.41 | 1.452 | 5.76** | 1.176 |

| The cost of flight and accommodation is generally high. | 4.48 | 1.336 | 5.77** | 1.314 |

| The exchange rate of foreign currency is generally low. nowadays. | 4.31** | 1.299 | 2.96 | 1.697 |

| My interest in travel for sport event tourism is increased due to the Rio Olympics in 2016. | 5.03 | 1.360 | 5.14 | 1.880 |

| Level of importance in aspects for sport event tourism | ||||

| Excitement about sport event | 5.46 [2] | 1.212 | 5.44 [4] | 1.590 |

| Additional activities related to sport event/sport team | 4.32 [7] | 1.515 | 4.78** [7] | 1.708 |

| Other tourist attractions | 5.01 [3] | 1.301 | 5.89** [2] | 1.294 |

| Transport infrastructure and transport service | 4.99 [4] | 1.076 | 5.73** [3] | 1.351 |

| Quality of accommodation | 4.72 [6] | 1.007 | 5.26** [5] | 1.315 |

| Safety level | 5.73 [1] | 1.005 | 5.97 [1] | 1.262 |

| Attitude of local residents at destination | 4.99 [4] | 1.048 | 5.15 [6] | 1.459 |

** The result of t-test is statistically significant and higher than Brazilian respondents at the 0.01 level (2-tailed)

Table 4 shows the correlation coefficients of the sport event tourism determinants in a matrix form of the two respondent groups. The statistically significant coefficients of over 0.4 are highlighted in bold, indicating that there is at least a certain degree of relationship between some of these determinants. Referring to the mag-nitude of the correlation coefficients which range from weak (r = 0.1-0.3) to moderate (r = 0.4-0.6) in this study (Dancey & Reidy, 2011), more pairs of correlation are observed in Brazil (15 pairs) than in Hong Kong (12 pairs). Both territories have 4 common pairs of moderate correlation coefficients, which appear between: (1) transport-other tourist attractions,

(2) transport-accommodation, (3) safety-transport, and (4) safety-accommodation. Specifically, transport-accommodation relation is the strongest among the two places, as both received a correlation coefficient of r = 0.6. The transport provision is associated with all other aspects in Brazil.

Table 4 Correlation coefficients of sport event tourism aspects in Hong Kong and Brazil

| Hong Kong | Excitement of sport event | Additional activities related to sport event/sport team | Other tourist attractions | Transport infrastructure and transport service | Quality of accommodation | Safety level | Attitude of local residents at destination |

| 1. Excitement of sport event | - | 0.467** | 0.007 | 0.173* | -0.012 | 0.047 | -0.018 |

| 2. Additional activities related to sport event/sport team | - | 0.129 | 0.118 | 0.103 | 0.032 | 0.046 | |

| 3. Other tourist attractions | - | 0.500** | 0.317** | 0.381** | 0.248** | ||

| 4. Transport infrastructure and transport service | - | 0.600** | 0.532** | 0.400** | |||

| 5. Quality of accommodation | - | 0.417** | 0.303** | ||||

| 6. Safety level | - | 0.553** | |||||

| 7. Attitude of local residents at destination | - | ||||||

| Brazil | Excitement of sport event | Additional activities related to sport event/sport team | Other tourist attractions | Transport infrastructure and transport service | Quality of accommodation | Safety level | Attitude of local residents at destination |

| 1. Excitement of sport event | - | 0.397** | -0.005 | 0.261** | 0.096 | 0.124 | 0.114 |

| 2. Additional activities related to sport event/sport team | - | 0.118 | 0.280** | 0.257** | 0.111 | 0.190* | |

| 3. Other tourist attractions | - | 0.482** | 0.449** | 0.369** | 0.193* | ||

| 4. Transport infrastructure and transport service | - | 0.600** | 0.542** | 0.359** | |||

| 5. Quality of accommodation | - | 0.596** | 0.351** | ||||

| 6. Safety level | - | 0.376** | |||||

| 7. Attitude of local residents at destination | - |

** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed)

* Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed)

4.2 Models of sport event tourism

The results of the MLR testing models of sport event tourism determinants are shown in Table 5. Four models are established, including the interpretation for yearly and infrequent events for each group. These models pass the multicollinearity test as all variance inflation factors are below a critical value of 3.0 (Fox, 1997). The interests in being a tourist of yearly and infrequent sport events are set as the dependent variables separately, whereas the sport event tourism determining aspects are independent varia-

bles. The overall fit of the models is low with adjusted R-Squares ranging between 0.151 and 0.259, but they are considered acceptable with a value of over 0.1 in terms of behavioural studies (Hair, Sarstedt, Hopkins & Kuppelwieser, 2014). In addition, to the satisfaction of Cronbach’s alpha (over 0.7), the models are found reliable because the F-values are statistically significant (p ≤ 0.01), and the Kurtosis values among the variables ranging between -0.326 and 1.360 are acceptable to prove normal univariate distribution (Trochim & Donnelly, 2006).

Table 5 Models of sport event tourism in Hong Kong and Brazil

| Model of Hong Kong | Respondents from Hong Kong (n=134) |

| Interest in yearly sport event tourism [Coefficient (t-value)] | |

| Constant term | -0.403 (-0.566) |

| Excitement about sport event | 0.433 (5.512)** |

| Adjusted R-square | 0.181 (F=30.378)** |

| Interest in infrequent sport event tourism [Coefficient (t-value)] | |

| Constant term | -2.314 (-2.548)* |

| Excitement about sport event | 0.350 (4.143)** |

| Attitude of local residents at destination | 0.223 (2.980)** |

| Additional activities related to sport event/sport team | 0.196 (2.318)* |

| Adjusted R-square | 0.259 (F=16.516)** |

| Model of Brazil | Respondents from Brazil (n=151) |

| Interest in yearly sport event tourism [Coefficient (t-value)] | |

| Constant term | 1.150 (1.894) |

| Additional activities related to sport event/sport team | 0.284 (3.468)** |

| Excitement about sport event | 0.194 (2.365)* |

| Adjusted R-square | 0.151 (F=14.313)** |

| Interest in infrequent sport event tourism [Coefficient (t-value)] | |

| Constant term | 1.633 (2.511)* |

| Excitement about sport event | 0.383 (5.065)** |

| Transport infrastructure and transport service | 0.173 (2.289)* |

| Adjusted R-square | 0.201 (F=19.831)** |

** Coefficient is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed)

* Coefficient is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed)

t values in parentheses (independent variables exhibiting t-values <1.0 are excluded)

The models commonly reveal that “excitement about sport event” is an important and significant determinant which influences the interest in being a tourist at sport events, regardless of the frequency of the event. This factor acts as the sole and moderate determinant to yearly sport event tourism among Hong Kong respondents (r=0.433). For infrequent event travel by Hong Kong respondents, two other factors affect the level of interest: “attitude of local residents at destination” and “additional activities related to sport event/sport team”, all at a weak level of influence. The last aspect is also important to the Brazilian group, contributing to their interest in yearly sporting event travel. For the interest in infrequent events among the Brazilians, “excitement about sport event” and “transport infrastructure and transport service” both influence this group.

5 DISCUSSIONS

The level of incentive of potential sport event tourists is much greater in Brazil than it is in Hong Kong. This is primarily reflected by higher levels of interest in being a sport event tourist at yearly and infrequent events, even though both groups had a similar level of increase in such travel interest after the Rio Olympic Games. Brazilian respondents are keen to be fans at sport events and of sport teams and are willing to watch a greater variety of sport events compared with the Hong Kong group.

Regarding travel characteristics, both respondents tend to prefer travelling for sport event tourism for about 6-8 nights (18% for Hong Kong and 11-22% from Brazil), although the former group appears to have two divergent market segments for short and long periods of stay. In general, the Brazilians are willing to spend over US$2,500 for a trip, whereas Hong Kong respondents report being willing to spend US$1,501-2,000 per trip. The results of the Hong Kong survey echo the preceding findings from a market study in 2014, i.e., 6-9 nights of duration and an average spending of about US$1,700 per trip (MasterCard, 2015).

There is a significant difference in travel characteristics of sport event tourists from Hong Kong and Brazilian cities. The Brazilians also have a longer average duration of sport event trips, as well as a larger expected amount of trip spending. In this connection, however, the Brazilian respondents tend to perceive having more obstacles to taking a sporting event trip. The difficulty is found to be relevant to the costs of event ticket price, accommodation, and the respective low currency exchange rate. The last aspect particularly hinders the incentive of outbound sport event travel by Brazilians as it may further magnify the adverse effect together with the cost factor.

There appears to be a closer interrelationship between sport event tourism determinants among Brazilian respondents given relatively more significant correlations across variable pairs. The strongest relationship is neither directly relevant to the nature of a sport event, nor to related activities. The major association between these literature-based determinants to sport event tourism comes from tourism operation, such as transport, accommodation, and tourist attractions readily available in respective destinations. Moreover, safety was attached to more association with all tourism infrastructure and services in Brazil, e.g., accommodation and transport factors. The safety factor is also the paramount important consideration among Hong Kong and Brazil respondents when choosing a sport event tourism destination. This concurs with findings from the previous study that safety plays a critical role in deriving an interest in travelling to Brazil for sport events and other tourist activities (Rocha & Fink, 2017).

Deriving from the models of interest in sport event tourism, the single shared determinant in affecting the incentive level for this form of tourism is the excitement or the competitiveness of the sport event itself. Although the models have a relatively low explanatory power in predicting the influential factors affecting the sport event tourism incentive, all the extracted statistically significant attributes in the models can still allow DMOs or other sport event tourism operators to draw important conclusions about the relationships and directions of the key determinants encouraging sport event travellers.

6 CONCLUSION AND IMPLICATIONS

This study largely reveals the consideration of outbound sport event tourists in Hong Kong and Brazil. The postulation that sport infrastructure, tradition, and culture in Brazil tend to foster a stronger potential market of sport event tourists than a typical urban destination like Hong Kong is largely confirmed. The travel incentive, ability, and characteristics are found to be very different between Brazilian and Hong Kong residents. Such disparity may nevertheless allow DMOs to cre-

ate tourist products in the short term, and city governments to develop sport attractions and nurture an atmosphere for sport culture in the long term.

Nonetheless, the findings of weaker associations between sport event-relevant aspects and tourism operational aspects suggest that sport event tourism is still in an early stage of development. Its perception is relatively detached from the aspects of tourism operation. Safety in Brazil is still the critical issue affecting a traveller’s willingness to visit the country, and this matter even influences Brazilian respondents’ considerations regarding travel. The information from the prediction models is valuable when generating important observations about how the DMO of a city should create an influential image based on determining attributes to attract potential sport tourists. The weak models indeed indicate the presence of other external factors in the decision about traveling to a city for sport events (Abelson, 1995). In sum, both territories have a long way to go, especially in terms of transcending sport culture to soft power and sustainability of sport tourism (Girginov & Hills, 2008; Grix et al., 2015).

The popularity of sport event tourism among Hong Kong outbound travellers lags behind the Brazilian potential. Even though the cost of travel and a relatively favourable exchange rate shape a good foundation for outbound travel among Hong Kong people, they still consider sport event tourism a niche market and a secondary purpose. To both territories, finding a way to sustain the effect of sport mega-events (e.g., Rio Olympics 2016 in Brazil and the East Asian Games 2009 in Hong Kong) should be a key to success based on coherent marketing and branding between sport events and tourism (Smith & Stevenson, 2009), as shown in some cases such as Barcelona, Athens and Beijing (Gilmore, 2002; Lee, 2010; Fola, 2011). The sustainability of tourism and the subsequent urban (re)development should keep the triple-bottom-line principle, such as social (Manzenreiter, 2010; Hiller & Wanner, 2011; Minnaert, 2012) and economic (Müller, 2012, 2014) perspectives.

A major limitation of this paper lies on the low explanatory power of the regression-based prediction for similar conditions in another city. Even so, the statistically significant information provides hints to the important determinants to the incentive of sport event tourists in the two places (Abelson, 1995). The two separate surveys may impose uncertainty in comparative analysis or parallel observation, and this problem was mitigated through a series of reliability and validity tests during the process of data collection and before data analysis. Although the high proximity to the 2016 Olympic Games in Brazilian cities may explicitly affect the interest in sport event tourism of their respondents, such effect is yet unverified through an empirical proof. Lastly, small sample sizes limit the representativeness of the results. It is believed that this study takes a pioneer step to conduct a comparative analysis in sport event tourism between the two regions. A larger-scale research is deemed necessary to include a few more cases of different characteristics for further study.