1 INTRODUCTION

Owing to its characteristics, tourism is an activity particularly sensitive to crises. Many tourism businesses have gone bankrupt, or have seen their business highly affected by crises resulting from wildfires, earthquakes, tsunamis, health scares, political and social unrest, economic crises or mismanagement, just to name a few. In this context, it is not surprising that tourism researchers started to devote their attention to the study of crisis management. Research on crisis management in tourism has grown considerably over the past 15 years, with this impetus traced back to the disaster management framework put forward by Faulkner (2001). As the tourism industry grew and the impacts of crises became more dramatic, so did the interest in the topic. Crisis management in tourism has recently been the subject of two literature reviews (Hall, 2010; Mair, Ritchie & Walters, 2014), which have attempted to shed light on the progress made so far, as well as to identify research gaps and opportunities. Mair et al. (2014) found six key themes covered by the tourism crisis management literature: communication between stakeholders, media sensationalism, marketing messages, disaster-management planning, destination image and reputation, and the changes in tourist behaviour.

Despite receiving much attention in the crisis management literature, the origins of crises in tourism have been little researched. Origins of crisis referred to the events that trigger a crisis. Understanding the origins and types of crises is very important for several reasons. First, it can help managers to spot a crisis beforehand and prevent it from happening. Secondly, it can make the managers understand what kind of impact the crisis could have. Third, it could show a pathway, in terms of how to react to them (Coombs & Holladay, 1996; Glaesser, 2004). Finally, when the wrong approach has been used to deal with a crisis, it can help managers to identify possible subsequent crises (Tse, So & Sin, 2006). Understanding the origins of crisis is, thus, a fundamental step to prepare an organisation for crises so that it can deal with disruptive crises events on a proactive basis. Therefore, the fundamental part of crisis management is about understanding the origins and types of crisis (Gundel, 2005).

The few academic papers on crisis management in the meetings industry only focused on the process of crisis preparedness and the perception of meeting planners towards crises (Hilliard, Scott-Halsell & Palakurthi, 2011; Kline & Smith, 2006; Smith & Kline, 2010). Despite their important role in managing crisis, little research has been carried out on the strategies adopted to manage crisis within the meetings industry. This paper aims to address these gaps and explores crisis management perceptions and practices for the Meetings industry by considering the views of Turkish Meetings managers from two perspectives: origins of crisis and crisis management strategies.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Crisis Management in Tourism

Crisis management has received increasing attention by academics, with the earlier studies tracing back to the 1960s (Hermann, 1963). Due to the growing number and impact of crisis, research on the topic has intensified the 1990s (Pauchant & Douville, 1993; Faulkner, 2001; Ritchie 2004). Most of these studies have slight different perspectives when it comes to the approach adopted. Jacobsen and Samuelsen (2011) have distilled the work of a number of authors and identified two main approaches for defining crisis. The organisation centred approach, describes crisis as a disruptive event in the organisation’s existence (see, for example, Fearn-Banks, 1996), while within the stakeholder-focused approach, stakeholders are viewed as playing a central role to the perception and attribution of importance and meaning to a crisis. Within the tourism literature most studies focus on the destination preparedness and response to crisis events (Faulkner, 2001; Paraskevas & Arendell, 2007; Sausmarez, 2013), with stakeholder coordination assuming the key role in the successful management of crises. Fewer studies have been developed from the organisation approach, with the existing studies focusing on crisis management policies, practices and procedures (e.g. Cioccio & Michael, 2007; Ghaderi, Puad & Henderson, 2014). Studies on the more atomistic personal approach, whereby the personal attitudes and experiences of tourism professionals towards the management of crisis are researched, are virtually non-existent. A recent review of the main themes within the tourism literature (Mair et al., 2014) confirms this assertion.

Both the organisation-centred and the stakeholder-focused approaches pointed out common features and trends. This includes a prevailing view of crisis as a threat, unpredictable and with multiple uncertain origins that cause negative outcomes for an organisation. But also, as argued by other crisis researchers, a turning point, which may also have also positive connotation. For instance, Ulmer, Seeger and Sellnow (2007) and Pauchant and Douville (1993), challenged the view of crisis as a threat, focusing their studies on the opportunities and learning potential presented by organizational crises. Two recent studies within the tourism literature have specifically focused on organisation learning in the aftermath of major crisis (Ghaderi et al. 2014; Rodriguez-Toubes, Brea & Torre, 2014).

2.2 Crisis Management in business tourism

While crisis management is tourism has been the focus of several studies over the years, research specifically focusing on crisis management in business tourism is almost absent in the literature. Some research (Henderson, 2013; Wu & Walters, 2016) has found that business tourism tends to be more resilient in the context of crises than leisure tourism. Wu and Walters (2016) suggested that a decrease in business travel flows is related to how essential the trip is, with business travel being more essential than a leisure trip. Given the resilience of business tourism, Wu and Walters (2016) concluded that marketing efforts should initially be focused on business tourism, including the meetings sector. Others (e.g. Campiranon & Arcodia, 2008) pointed out that business trips, such as to attend meetings and conferences, are very susceptible to crisis, and when they happen destinations highly dependent on business travel attempt to attract leisure tourists in order to increase tourist flows. According to Henderson (2013) and Rose, Avetisyan, Rosoff, Burns, Slovic and Chan (2017), business trips are cancelled due to practical reasons as well as fear. Liability is among the most important practical reasons for organisations to reduce or even eliminate business travel to a crisis destination (Campiranon & Arcodia, 2008).

Two empirical studies on crisis management in the meetings sector were found, with both focusing on crisis preparedness. Smith and Kline (2010) focused on understanding how important meeting planners found planning for crisis preparedness. The study found that certain types of organisations perceived crisis preparedness as more important than others, notably the larger the number of the meetings organised, the more important crisis preparedness was perceived to be. The study also examined the use of crisis preparedness initiatives, which were found to be more used by regulated organisations. Hilliard et al. (2011) also focused on the use of crisis preparedness measures, identifying five categories: procedural/technical, relationship-oriented, resource allocation, Internal assessment, expert services. The study also assessed use of these measures across industry segment, organisation size, size of the largest meeting planned, number of meetings planned, and meeting planning experience. Similar to Smith and Kline (2010), some differences in use were found, notably related to the first three of the five variables.

2.3 Crisis management strategies

Recognising that strategic planning is crucial to cope with crises in an effective way, several studies focused on crisis management strategies (e.g. Hart, Heyse & Boin, 2001, Hale, Hale & Dulek, 2006; Hargis & Watt, 2010). A large proportion of these studies examine the strategies to cope with crises by explaining that they vary according the magnitude of the crisis incidents as well as the stages a crisis goes through: pre-crisis, crises and post crisis (Heath, 2003). One of the earliest and widely accepted models (Mitroff et al., 1987) outlines the stages of crisis and explains the strategies to cope with each stage separately. The authors covers crisis management in four phases, but can be included in the above three stages: detection (pre-crisis), crisis and repair & assessment (post crisis). This implies that organisations can be proactive if they focus on preventing the crisis (pre-crisis) or reactive, if their focus is on dealing with crisis once it has occurred (crisis and post crisis).

Within tourism, a number of authors have focused on crisis management strategies, with a number of holistic models of crisis management built around the crisis life cycle (e.g. Faulkner, 2001; Ritchie, 2004; Santana, 2004; Pforr & Hosie, 2008). Within the meetings context, Kline and Smith (2006) proposed four main phases necessary for meeting planners to understand and strategically overcome a crisis: prevention, awareness, response and recovery. These strategic-level models assume that a holistic and proactive approach to crisis management is required through three issues: developing proactive scanning and planning before crisis occur (pre-crisis); implementing strategies when crises occur (crisis); and, evaluating the success of these strategies to guarantee constant improvement of crisis management strategies (postcrisis) (Ritchie, 2004).

In addition to this work on crisis management holistic models, some tourism researchers focused on specific stages of the crisis management process. Research on the earlier stages of the process includes Anderson (2006) with her study on crisis preparedness. Much of the tourism research is devoted to the long-term post-crisis event management (e.g. Ghaderi et al., 2014; Sausmarez, 2014; Mair et al., 2014), with few studies focused on the awareness of a crisis and the immediate response after becoming aware of a crisis. Although not specifically devoted to the latter, Jallat and Shultz (2011) covered a hotel’s evacuation procedures and immediate management of the crisis, while one study (Paraskevas & Altinay, 2013) uncovered crisis detection practices by hotels.

2.4 Origins of crisis

Many crisis typologies have been put forward over the years. These can be broadly divided into two categories: one-dimensional (e.g. Pearson & Mitroff, 1993; Lerbinger, 1997; Coombs, 1999; Coombs, 2004; Seymour & Moore, 2000) and bi-dimensional. One of the earliest, and often cited, bi-dimensional typologies was put forward by Mitroff et al. (1987). Their typology established that crises can occur inside (internal) or outside of the organisation (external) (the locus of the crisis), and be caused primarily by technical/economic breakdowns and those that are caused by people, organizational or social breakdowns (content of the crisis). It is important to make this classification, because it gives a clear understanding to what extent people have control over the origins of the crisis. For instance, internal and human/social/organisational crises are considered to be more controllable than external and technical/economic crises. A more recent typology (Coombs & Holladay, 1996) classifies crises on intentionality (intentional or unintentional) and control (internal or external).

Several authors have suggested that using classifications may sometimes be difficult. In their comment about Mitroff et al.’s (1987) typology, Choi, Sung and Kim (2010) noted that in today’s world technical and economic factors are often related to people. Thus, they are integrated to a certain level. For instance, computer break-downs and other technological problems are highly associated with human failure. In a similar vein, Caldiero, Taylor and Ungureanu (2011) pointed out that fraud crises have been classified under different Coombs’ (1999) typologies. Considering the long list and uniqueness factor of potential crises, it is hard for the organisations to form a general framework to prevent them. Nonetheless, it is still important for organisation to develop their crisis typology in order to fully prepare the organisation for the different types of crises (Choi et al., 2010).

As it was noted in the introduction, despite the growth in crisis management research over the past 15 years, there is virtually no research on the origins of crisis in tourism. One of the main reasons for this lack of research on the topic is the fact that existing research has focused on crisis management associated to specific crisis events, such as natural disasters (e.g. Cioccio & Michael, 2007; Rittichainuwat, 2013), terrorism (e.g. Paraskevas & Arendell, 2007) and political events (e.g. Sausmarez, 2013). Naturally, since the crisis under examination was clearly defined from the outset, researchers were not concerned with examining the topic. To date, only two attempts at developing crisis typologies were identified, one unidimensional (Tse et al., 2006) and one bidimensional (Faulkner, 2001) typology. A common feature of existing research on crisis management in tourism is their focus on external crisis. Although they are considered as crisis by both the general crisis management literature (Mitroff et al., 1987) and the tourism literature (Tse et al., 2006), internally generated crises have received scant attention in tourism research. Yet, organisations face multiple crisis events that are caused by its activities, whose resolution requires no involvement of external stakeholders or perhaps only as a small number (e.g. IT failure, one supplier does not arrive). While some of these crises can have a substantial effect on the company’s survival, most will have a short-term effect on the company’s operations.

3 METHODOLOGY

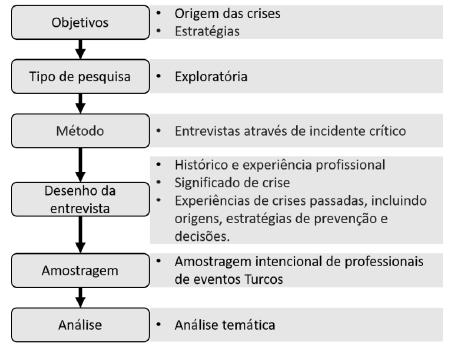

The methodological steps undertaken are summarized in Figure 1. Existing crisis studies have until often been conducted in quantitative approach, in the forms of statistical analysis. As a consequence, existing research on the perceptions about crisis management by meeting planners has often been based on adaptations from studies developed in other areas other than the meetings industry. Therefore, this study adopted an exploratory perspective through interviewing meeting planners about the origins of crisis and the strategies employed to manage them. Participants were asked to revisit past crisis experiences through the critical incident technique and therefore the focus is not on their experiences in the current organisation but on their entire experiences as a meetings professional. The technique is used in in-depth interviews, in which respondents talk about a significant event and express their feelings accordingly (Gremler, 2004). In this study, participants were asked to revisit crisis events they encountered and reflect on how they originated and how they managed them. One benefit of using the critical incident technique is that the decision about which situations presented a crisis was left to the participant rather than imposed by the researcher. Moreover, it was a basis for developing rapport between the participants and the interviewer as it made the conversation more personal, which is considered a significant factor in conducting more sincere in-depth interviews (Berg, 2007). In practice, participants ended up answering most of the questions about crisis management while they were explaining the crisis event.

The questions were prepared as open-ended, in order to conduct semi-structured, in-depth interviews. The initial questions focused on the participants’ professional background and experience. This was done to make participants feel comfortable by introducing themselves and to collect vital data about the participant was. Next, participants’ perceptions about what a crisis meant were explored. After that, they were asked to talk about a crisis they encountered. This included exploring a number of issues about the crisis experience including its origins, prevention strategies and decisions they had to make once the crisis had been triggered. The interviewer did not impose a particular definition of crisis to participants in order to capture their understanding of crises rather than a particular academic view on the concept.

In total, eleven meeting professionals from two organisations located in Istanbul, Turkey, participated in the study. Non-probability sampling in the form of convenience sampling was employed. Initially, meeting planners working for an organisation for which one of the researchers had worked in the past were approached. Eight employees of this organisation accepted to be interviewed. A second organisation was contacted and three additional interviews were carried out. Table 1 presents the profile of the participants. While participants came from two organisations only, the research did not focus on crisis management within that organisation. Many had worked for different organisations over their professional lives and used crisis experiences that happened while wor- king for other organisations. Recordings of the interviews were transcribed before proceeding with manually analysing the data. In order to identify themes, answers to each question were separated and specified in bullet point codes. This specification allowed most common answers to appear and main themes to be identified. Translation was carried out during the coding by one of the authors, who speaks Turkish and English fluently. During translation, some sentences were not suitable for word-by-word translation and the meaning had to be translated.

Table 1 Profile of the Sample

| Name | Gender | Years working in industry | Job title | Length (minutes) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ayla | F | 3 | Operations & Sales Support Specialist | 22 |

| Eda | F | 27 | Business Development & Vice President | 15 |

| Fatma | F | 2 | Sales Support Specialist | 18 |

| Halime | F | 2 | Customer Relations Manager | 16 |

| Irem | F | 10 | Customer Relations Manager | 27 |

| Kerime | F | 11 | Operations Project Manager | 20 |

| Leyla | F | 11 | Operations Manager | 31 |

| Cihan | M | 15 | Operations Support Manager | 15 |

| Demir | M | 6 | Sales Manager | 28 |

| Merve | F | 15 | Head of Operations Department | 20 |

| Yasemin | F | 13 | Operations Support Manager | 30 |

4 RESULTS

4.2 Origins of crisis

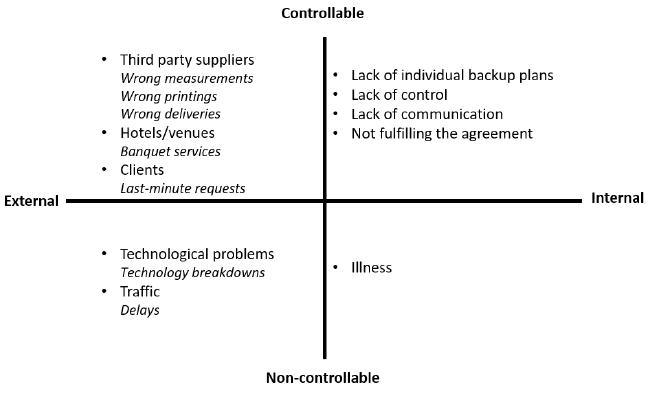

Meeting planners’ perceptions about how crisis are originated identifies the cause that led to the crisis. The results showed similarities with Mitroff et al.’s (1987) typology of crises and therefore an adapted version of the typology was developed. The internal and external axis was retained, however, the technical/economic and people/organisatiotional/social axis was replaced by degree of control (controllable/ non-controllable). Origins are controllable if processes can be put in place to prevent problems from arising such as through selecting reliable suppliers, working closely with clients and through adopting the right management practices to reduce the likelihood of problems arising. Non-controllable origins are those causes that are outside the control of the meeting organiser and therefore there is little, if any, ability to influence the appearance of a crisis. As showed in the Figure 2, participants identified multiple causes that can trigger a crisis. Using Coombs (2004) typology, the results show that meeting planners viewed crisis as originating in mainly technical error (technology or equipment failure) and human error (a person does not perform the job properly).

4.2.1 External / Controllable

External / Controllable factors occur outside of the event organiser and have a soft content, such as people. Halime’s (2 years experience, Customer Relations Manager) answer summarises the two main origins within this category when she states that “A crisis is something which happens either because of the client or because of the supplier”. Problems with third party suppliers include issues with decoration supplies, wrong printings and measurements, as well as those involving hotels and venues. Although strictly speaking event organisers cannot fully control the performance of these suppliers, buyers regard event organisers responsible for the performance of all suppliers. This is visible in Merve’s (15 years experience, Head of Operations) when she stated that “banquet services in hotels exhaust us. Because it is directly related with us, clients don’t care if it’s their fault”. Buyers view suppliers’ service delivery issues as the responsibility of the event organiser and if something goes wrong, then it is their role to sort it out.

Clients can cause a crisis through last minute requests, which are not in hand and therefore very hard to provide at the last minute. These last minute requests are expected however and therefore event organisers make sure they select suppliers who can be responsive to these last minute requests. Another issue with clients as a source of crisis results from the timings of the approval as demonstrated by Cihan (15 years experience, Operations Support Manager) when he stated that “clients always approve late, they always change their opinions. You need to expect that and get used to it in order to manage the crisis later on”. Demir (6 years experience, Sales Manager) separated crisis into two typologies, real and artificial crisis. He defined real crisis as an unexpected problem. On the other hand, when talking about the artificial crisis, he referred to the clients, which are hard to handle and calm down. He emphasized this point by explaining that “the most difficult thing about our job is to deal with people. Even though there are no crises, some clients just panic and try to take the control over. This is even harder to handle than a real crisis”.

4.2.2 Internal / Controllable

Factors over which the extent of control is high and control is independent of the influence of external organisations are classified as internal/controllable. Four respondents mentioned internal-controllable origins, including a lack of information/communication, a lack of individual back-up plans and long working hours of the team. Merve (15 years experience, Head of Operations) pointed out that it is customary for individuals to have their own back up plans and that they assume that others have them too. Problems may occur when some individuals have not undertaken their individual back-up plans. When this happens, they may fail to predict any potential problems as well as plan in advance for alternatives. A key point which included in the internal / controllable originated crisis (Choi et al., 2010) but was not mentioned by respondents was the existence of organisational crisis management plans. Participants seemed to struggle when asked whether their company had an organisational crisis management plan. The majority of the respondents stated that they did not have one, and also agreed that it was impossible to do them. The reason for that was mainly due to the people factor. Fatma (2 years experience, Sales Support Specialist) explained “Every crisis is solved at the field, during the event. We don’t know what we will encounter; it wouldn’t be realistic to have a plan”. Respondents did not seem to think the lack of an organisational crisis management plan could be a source for a crisis, due to failing to anticipate any problems and/or planning for when they occurred.

4.2.3 External / Non-controllable

External / Non-controllable factors refer to crises, which occur outside of the organisation and cannot be prevented. The participants identified two sources: technical problems and traffic delays. The difference to controllable factors refers to the fact that blame could not be attributed to the organiser, third party suppliers or the venues. In fact, Eda (27 years experience, Business Development & Vice-President) stated that “You can always encounter technical problems, they are very usual”. Demir (6 years experience, Sales Manager) gave an example of a technical problem he encounters: “If there is an event on a venue by the Bosporus and a big ship is passing by, the microphones always break down. We know that and we always take spare microphones to these events”. In such case, while the passing of a ship cannot be controlled, knowing that it is a possibility and the consequences that will be brought, affords the meeting organiser the opportunity to prepare a recovery should it happen. Others causes, such as traffic, are non-controllable and difficult to recover from. Demir referred to this problem when talking about his crisis event, saying “The artist couldn’t arrive because of the traffic. There was nothing to do, nothing”. Four respondents also mentioned the delays because of the suppliers. Merve (15 years experience, Head of Operations) stated this as “The most common problem we encounter, delays of the transfer vehicles”.

Natural/man-made disasters, one of the major external/non-controllable sources mentioned in the literature, was only mentioned by one participant. This is perhaps the most damaging type of crises as they could involve personal in injury or extreme hardship (Laws, Prideaux & Chon, 2007). Only Eda (27 years experience, Business Development & Vice-President), which had worked in the hotels industry for several years, mentioned that the hotel had “standard procedures for fires and big disasters”. This result contradicts previous studies, notably that of Smith and Kline (2010) on meeting planners’ perceptions about crisis preparedness, in which respondents associated crisis to natural or man-made disasters, like terrorist attacks or bomb threats. The reason why Participants in this study might not have mentioned natural disasters could be because they do not think it is their responsibility to do a crisis management plan that deals with this type of external/non-controllable cause. Meeting planners organise events in different venues, and they expect each venue to have its own crisis management plan, which will be activated should it be necessary.

4.2.4 Internal / Non-controllable

Few participants mentioned internal/non-controllable sources despite the fact that Mitroff et al.’s (1987) typology included several crises under internal and technical/economic part. Because the events industry is part of the services industry and is more related with soft concepts than hard ones, the only crisis in the meetings sector that could involve internal/non-controllable causes are technological problems such as computer breakdowns. Participants mentioned technological problems, however they did not refer to these problems as internal due to the fact that they do not own most of the technical/technological equipment they use in their events. The equipment used in meetings belongs to suppliers and therefore any technological problem is blamed on them (hence it is an external cause). An unexpected illness of a member of staff was the only internal non-controllable crisis mentioned by participants.

4.3 Operational strategies to manage crises

A second major area explored by the research focused on the strategies used by meeting planners to manage crises. Respondents referred to strategies when they talked about how they dealt with the particular crisis event they encountered. There are numerous theories and models of crisis management, some of which were covered in the literature review. In this research, the strategies employed by meeting planners are organised around Mitroff et al.’s (1987) four phases of crisis management: prevention/preparation, coping, recovery and learning.

4.3.1 Prevention/Preparation

In theory, prevention/preparation can be made at three levels: individual, event/project team and organisational. Participants stated that they engage in individual preparation activities in order to develop their individual back-up plans. Participants mentioned a number of strategies they employ to reduce the likelihood of any faults in the service delivery, including establishing contracts with suppliers and carrying out inspections ahead of establishing contracts or, once these are in place, before of the actual service delivery. At the event/project team level, the majority of the participants stated that they bring together individual-level strategies through writing scenarios for each event in order to create a flow and see the whole picture. Fatma (2 years experience, Sales Support Specialist) highlighted that by saying “We have pre-operation meetings before each event, we talk about the scenarios in detail and we go over the flow. This is a routine”. This is actually very common in event management, which usually comes in the form of Gantt charts (Shone & Parry, 2010). However, it was noted that these preparation actions are not implemented at the organisational level. Participants agreed that it would be impossible to have an organisational crisis management plan for two reasons: the length that such plan would take (“we [would] need to write an encyclopaedia”; Demir, 6 years experience, Sales Manager) and the dynamic nature of working environment (“it is not possible to follow a plan; we are working in a dynamic environment”; Kerime (11 years experience, Operations Project Manager). These aspects highlight the breadth, size, complexity and dynamism of organising events such as meetings, which according to the participants can only accommodate adaptable preparation processes that should be dealt with at a more atomized level (individual or team). This attitude reflects a ‘reactive mindset’ (Ritchie, 2004) which is common in the tourism industry (Mair et al., 2004).

4.3.2 Coping

The study identified two types of coping strategies: at the personal level and at the interpersonal level. From a personal point of view, participants highlighted the key characteristics required to successfully cope with a crisis should it happen. The two main traits required to deal with such situation are to remain calm and be decisive, while trying to avoid letting emotions take over. Crisis situations require people who can stay calm in order to make rational decisions (Hadley et al, 2011), thus meeting planners’ perception of this key trait is congruent with the crisis management literature. Merve (15 years experience, Head of Operations) further noted that it was important avoid denial and instead to “acknowledge the situation and focus on the solution”.

At the interpersonal level, strategies directed at both the clients and the suppliers were uncovered. At the client level, participants emphasised that they put a lot of effort in preventing clients from understanding a crisis situation was taking place. The following quote illustrates this concern: “If the crisis would be reflected to the client, it would have been a bigger problem” (Cihan, 15 years experience, Operations Support Manager). Service failures can lead to consumer negative emotional reactions, which in turn can cause operational (or even strategic) constraints on the organization (Kähr, Nyffenegger, Krohmer & Hoyer, 2016). Meeting planners recognised this and therefore concealed service delivery problems from clients as much as they could, in the hope that they could resolve them before substantial impact on service delivery became evident.

At the supplier level, coping with a crisis involved liaising with suppliers in order to find a solution that would attempt to solve the crisis before it became apparent to the client. This often involved resorting to extraordinary business practices such as contacting suppliers outside normal business hours. Cihan (15 years experience, Operations Support Manager) said he has had to contact suppliers at 3am, a practice that is not unusual as confirmed by Kerime (11 years experience, Operations Project Manager) when she stated “If we need to solve the crisis, sometimes we even wake up the supplier and make him/her open the shop in the middle of the night”. Irem (10 years experience, Customer Relations Manager) highlighted three traits that are required for successful resolution of a crisis when a supplier’s involvement is required: “good persuasion skills”, “never giving up” and “to push every limit you can until you have a solution”. These answers also clearly indicate the importance of maintaining good relationships with suppliers because without them these uncommon business practices would not be possible. This result supports earlier findings that cooperation and communication between stakeholders is vital for successful crisis resolution (Mair et al., 2014).

4.3.3 Recovery

When it became impossible to contain a crisis and clients became aware of it, or were affected by it, meeting planners focus their attention on damage recovery. The majority of the participants talked about crises, which were not reflected to the clients and therefore recovery was little mentioned in the interviews. Nonetheless, two participants did reflect on what the best recovery strategies would be. Irem (10 years experience, Customer Relations Manager) emphasised the important of having a solution rather than just acknowledging that there was a crisis. The need to be honest and sincere with the client was also mentioned as a recovery strategy by Merve. According to her, by adopting such approach ”you won’t lose them for good”. These two participants also mentioned the issue of locus of responsibility. When it was clear that the crisis originated due to the company’s fault, the view was that the company should acknowledge responsibility and, eventually, compensate the client because “to compensate is as important as solving it” (Irem). Attribution has been found to influence how the consumer reacts (Dabholkar & Spaid, 2012) and meeting planners seem to be conscious of this when attempting to recover from a service failure. Offering a monetary or in-kind compensation is common when service failure is more serious, with research showing that it has the strongest recovery effect (Roschk & Gelbrich, 2014).

4.3.4 Learning

Throughout the interviews, there was little evidence of learning about crisis management. It appeared that the participants did not take the evaluation phase and the learning actions in to consideration. Any learning activities were carried out automatically at an individual level through personal reflections about the crisis event they experienced. This was evident when Ayla (3 years experience, Operations & Sale Support Specialist) stated that crises are “an opportunity to (…) improve ourselves individually”. The use of those experiences to develop a crisis management plan was rejected, mainly because participants argued that each event is unique and it holds the people factor in it. In addition, a crisis management plan would not be able to contemplate the creativity element required to crisis decision-making and could prevent people from thinking practically. Leyla (11 years experience, Operations Manager) explained this situation the following way:

“Even though the company decides to have twenty crisis management plans, I would do what I do on the field. Because I am the one who sees clients’ responses. It’s about action and reaction”.

Irem (10 years experience, Customer Relations Manager) also emphasized that by saying “It is better to take the initiative. There are some crises, which you cannot foresee. Thus, you cannot write them down”. Cihan (15 years experience, Operations Support Manager) emphasised spontaneity issues by saying

“When you encounter a crisis, you need to be very quick. If there is a handbook for that and you try to follow the rules, you cannot take the initiative; you cannot find the best solution for the particular situation. I don’t believe these should be standardised”.

Thus, these statements indicate that not having an organisational crisis management plan is considered as a strategy, rather than a cause for a crisis (an origin). Participants appeared to reject the development of formal crisis management plans due to their perceived lack of flexibility, which the literature (Lalonde & Roux-Dufort, 2013) and themselves recognize is a vital competency for successful crisis management.

4.4 Crisis as an opportunity

Participants were clear that they expect crises to happen at every event and that many see them as an opportunity involving both personal and organisational benefits. At a personal level, crises provide a challenge, a shift away from routine. Once a crisis is solved, according to Ayla (3 years experience, Operations & Sale Support Specialist) “it’s the best feeling in the world”, making him “very happy”, suggesting that crises provide personal gratification. Demir (6 years experience, Sales Manager) emphasised the organisational benefits of crises. According to him

“Being able to solve crisis is an added value to our job. If everything would go ordinary as it is planned, it will be condemned to stay as average. When we handle a crisis, our credibility increases”.

This was supported by Halime (2 years experience, Customer Relations Manager) when she stated that

“When we solve a crisis, clients see us as their solution partners, not only as meeting planners” and Ayla who claimed that “it is an opportunity to show our professional work”.

This finding supports earlier stances that crises are an opportunity for the organization (Ulmer et al. 2007; Pauchant & Douville, 1993; Ghaderi et al. 2014; Rodriguez-Toubes et al., 2014), with the benefits identified both at the individual and organisational level.

5 CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Crisis management research in tourism tends to focus on crisis management after a specific crisis event (or number of events), rather than the study of generic crisis management, which is not tied to specific events (Mair et al., 2014). One consequence such make-up is that research has tended to focus on large-scale crises resulting from natural disasters or political/economic events. However, at an organisational level, managers are confronted with many events on a day-to-day basis that they consider to be crises. In fact, this study shows that when devoid of focus on a specific crisis, meeting organisers emphasise more the operational crisis that emerge during the day-to-day operations than highly infrequent crisis events. Therefore, to meeting planners crises are more about service failures than major disruptive events that question the organisation’s existence as per the traditional definition of crisis (Fearn-Banks, 1996).

The fact that meeting planners viewed service failures as crises is not surprising as it could be argued that service failures are crises albeit of a smaller scale and impact. In fact, one could argue that major service failures can meet the requirements of a crisis as they can affect the organisation’s existence. For example, if a meeting planner was to face wide scale food poisoning at major event, while a service failure its magnitude could lead the company to cease to exist. Therefore, while service failure and crisis share some differences, notably in the magnitude of the threat, they are similar enough and hence, as shown in this paper, crises management frameworks can be employed to understand crises that are in essence service failures.

Meeting organisers are to some extent crisis prone organisations (Hilliard et al., 2011) and therefore face large and small-scale crises every day due to the large number of stakeholders involved in the planning and managing the processes required to organise meetings (Smith & Kline, 2010). Each stakeholder brings a potential uncertainty, which increases the complexity of meeting planning. The main function of meeting planners is to bring together these stakeholders and therefore, in the case of a crisis or service failure, it is their responsibility to be able to manage it effectively. According to the results of this study, meetings are highly prone to smaller scale, operational crisis in particular for two reasons. First, they are mainly aggregators of services offered by a number of external organisations, where services used vary with each delivery (e.g. they don’t use the same hotel or conference venue all the time). Second, these external services are operated and managed by a variety of staff, making the industry human resource intensive and hence prone to human error.

The main findings indicate that the majority of the crises induced by service failures are originated from external and people related factors, even though people related dimension was defined as controllable to a certain extent in the main findings. The respondents mostly mentioned third party suppliers, as well as the venues and the hotels they work with. Another common agreement was about clients and their last minute requests. However, these were also referred to internal factors, such as lack of communication by some respondents. Technological problems were seldom mentioned, and they were only related with external parties. Taken together, these results suggest that meeting planners tend to attribute crises events to others than themselves, a process identified in the tourism industry before (Ascanio, 2008). Attribution processes are closely related to crisis management and service failure as it is common for stakeholders to attempt to examine the responsibility for the problem because the locus of responsibility carries potential affective and behavioural consequences for the organisation (Coombs, 2007; Dabholkar & Spaid, 2012). For meetings organisers, this could involve reputation and financial costs (compensation).

Pre-operation meetings, individual back-up plans, writing action plans and check lists were the most common statements which were referred by meeting planners as strategies to prepare/prevent crises. Strategies employed during a crisis were mostly related with their emotional and characteristic states. The examples put forward were staying calm, and not reflecting the situation to the client, with the main objective when surviving a crisis centred on not losing their customers. This focus on customer retention has been previously found elsewhere (Mitroff & Anagus, 2001). At the recovery stage, right after the crisis occurs, meeting planners tend to compensate the damages to their clients, which is a reputation management strategy (Hargis & Watt, 2010).

Meeting planners are fully aware of what could cause a crisis and employ a range of strategies to manage them. Results show that crisis management is carried out at an individual level, but that there are low levels of formalisation at the organisational level, to the point that they rejected the idea of developing crisis management plans. This rejection appears to originate on the type of knowledge they perceive to be essential in successfully managing crises, with crisis management associated to tacit rather than explicit knowledge. Tacit knowledge is “practical, action-oriented knowledge or ‘know-how’’ based on practice” (Smith, 2001, p. 314), facilitates innovation (Brown & Duguid, 2000) and is deployed using face-to-face (Hansen, Nohria & Tierney, 1999). Participants strongly rejected the idea of developing crisis management plans because the situation they encounter may require creative, and unique solutions that would not feature in such plan. Moreover, dealing with potential issues requires a high level of spontaneous decision-making, which involves face-to-face contact with suppliers or customers. Deal with crises through formalising procedures and establishing work processes, the essence of explicit knowledge, was viewed as detrimental to successful crisis management, mainly as it would affect their ability to deploy tacit knowledge.

5.1 Implications for practice

Understanding origins and operational strategies can be useful to meetings professionals, as each crisis type related to service failure could be better tackled through different strategies. For instance, management strategies for external/controllable origins i.e. third-party suppliers, clients; are mostly related with managing individual client/supplier characteristics and event experience. On the other hand, internal/controllable originated crises can be managed by training, leading to better prevention and/or preparation. External/non-controllable originated crises require coping and learning strategies. For instance, during a natural disaster event, the best strategy a meeting planner could use is keeping people calm and directing the participants according to their emergency plan. For the internal / non-controllable problems, i.e. computer break-downs at the office, reputation management strategies are suggested, due to the risk of losing confidential data, which can result in decrease of companies’ reputation.

The rejection of crises management plans, while rationally explained, is concerning as professionals failed to understand that just preparing those plans could help prevent crises, or even better prepare them for their management should they happen. This may be due to cultural reasons, appearing to reflect the fact that “societies in [the Middle East] have practices that do not engage in future oriented behaviours such as planning and investing in the future” (Kabasakal & Dastmalchian, 2001, p.486). Practitioners would benefit from understanding that the lack of formal crisis management plans, while offering flexibility and spontaneity in decision making, could also be the origin of some of the crises they face due to service failures. The sharing of experiences about effective crisis management planning, which is more common in regions like Northern Europe, could be instrumental in demonstrating the benefits of explicit knowledge, ultimately leading Turkish meeting planners to adopt formal crisis management tools such as crisis management plans.

5.2 Implications for research

This paper contributes to the literature by demonstrating that crisis management frameworks can be employed to examine crises that are essentially service failures. A first implication of the study is that the distinction between the notions of service failure and crisis may be an artificial rather than a real one. Consequently, researchers planning studies on crises-service failure should consider looking at both literatures in order to integrate both bodies of knowledge. With regards to future themes, the cultural influences on perceptions and practices of crisis-service failure management warrants further research. Comparative studies across countries, perhaps linking organisational culture to country culture, could be undertaken in order to further understand how culture influences individual and organisational practice. The individual and organisation aspects of crisis-service failure management also deserves further research. In the Turkish context, the meeting professional appears to be largely independent in his/her management of crisis-service failure, but future research could examine differences across organisations and how leadership affects those differences. Finally, scales and questionnaire design, which can be more validly developed based on the findings of this exploratory research, should encourage researchers to undertake quantitative research in the area. For example, a detailed list of origins can now be included as elicited in this study.

texto em

texto em