1 INTRODUCTION

Tourism is one of the most important sectors of global economy, and strategic for regional development (Jackson & Murphy, 2006; Mabrouk, McDonald, Mocan, & Summa, 2008; Ferreira & Estevao, 2009; Aleksandrova, 2016). It is a multi-faceted activity, encompassing various actors and has on the territory a source of competitive advantage. In addition, tourism is an industry that contributes directly to regional development through the formation of inter-organizational networks such as clusters (Kunz, Schommer, Schneider, & Mecca, 2012; Silva, 2015).

The advantages of tourism clusters have increasingly prompted the attention and the creation of policies for the competitiveness of clusters by public authorities, organizations such as the World Tourism Organization, and the academia. Research on this topic aims at the understanding of the opportunities and advantages of regional inter-organizational networking, such as tourism clusters (Novelli, Schmitz, & Spencer, 2006; Jackson & Murphy, 2006; Ferreira & Estevão, 2009; Iordache, Ciochinã, & Asandei, 2012; Kunz et al., 2012; Borkowska-Niszczota, 2015; Aleksandrova, 2016). According to Fundeanu (2015), clustering allows a joint effort of the tourism companies, and encourages a greater coordination with other institutions. The coordination with these categories of institutions, which is closer within clusters, encourages the processes of innovation (Sohn, Vieira, Casarotto Filho, Cunha, & Zarelli, 2016), considered one of the key factors for competitiveness in tourism (Novelli et al., 2006).

For the United Nations World Tourism Organization [UNWTO] (n.d.) the formation of tourism clusters is an ongoing trend in several countries with the aim of promoting regional development and enhance innovation, competitiveness, and economic and social development. Therefore, it stands out that the debate about the tourism clusters is fostered by local development programs as an appropriate strategy to combat regional disparities and social inequalities (Borkowska-Niszczota, 2015; Yıldız & Aykanat, 2015; Martins, Fiates, & Pinto, 2016; Polukhina, 2016). In this context, the research aims to describe and analyze the central elements that characterize the formation of a tourism cluster in Balneário Camboriú, Santa Catarina, Brazil.

The city of Balneário Camboriú is located on the coast of Santa Catarina, Brazil, presenting from the second half of the 20th century a vocation for tourism. The municipality has approximately 128,155 inhabitants (Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics [IBGE], 2015), and received 600,000 visitors per month during high season4, in the year 2015 (Prefeitura Municipal de Balneário Camboriú, 2016, 2016).

To meet the objective we organized this article in five sections. In the introduction, we present the context, purpose and importance of the research, then it follows the theoretical framework, the methodology, the results and the final considerations.

2 CLUSTER: CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

Clusters are a set of organizations that operate in the same sector, located in the same geographic region and connected by means of 'buyer-supplier relations', or by technology of common property, common buyers or the same channel of distribution or concentration of workers (Cunha, 2007). Clusters are geographic concentrations of companies or institutions interconnected in a particular field or industry that include a set of industries and organizations vital to the competition (Porter, 2008; Sölvell, 2008).

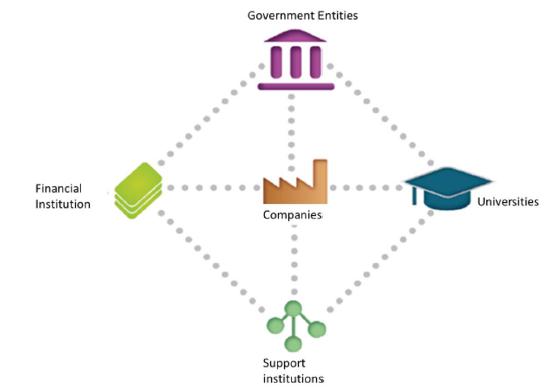

The definitions of cluster presented assume the location within a geographical territory of different agents working on behalf of a particular economic sector (Figure 1). Among these stands out the presence of private or Government-related associations (Casarotto & Pires 2001).

Authors like Casarotto and Pires (2001), Belso-Martínez (2006), Cunha (2007), Jenkins and Tallman (2010), Lundberg (2010), Porter and Kramer (2011), Saublens (2011), Wragg (2012), Li et al. (2012) and Yildiz and Aykanat (2015), highlight the importance of clusters for the promotion of competitiveness and regional development. In this respect, we should note that the formation of clusters is important to enhance regional economies and to reach relevant growth rates.

The existence of clusters promotes the generation of externalities (Waxell & Malmberg, 2007; NIE & Sun, 2015) by developing inter-organizational partnerships in order to achieve a high level of innovation and competitiveness (Yildiz & Aykanat, 2015). A cluster comprises a socioeconomic entity featuring a social community of actors working together in linked economic activities, making use of technological and organizational knowledge in order to generate products and services more competitive (Morosini, 2004; Porter, 2008).

Virtually all currents of thought about the clusters value the importance of cooperation (Martins et al., 2016) that occurs in different dimensions and can generate earnings, including: increased productivity, accelerate innovation and prompt the creation of new businesses (Lai, Hsu, Lin, Chen, & Lin, 2014; Yildiz & Aykanat, 2015).

The participation of enterprises in clusters contributes to adapt to fast changing markets and to adapt to new technologies, given that companies in clusters can work collaboratively to co-develop with the aim of increasing competitiveness and adaptation to change (Yildiz & Aykanat, 2015; Lai et al. 2014; Niu, 2010).

Social interactions and the links produced inside the clusters become key determinants for the exchange of knowledge and for the generation of technological innovation-related externalities (Hortelano, Pérez & Villaverde, 2015; Sohn et al., 2016).

However, Porter and Kramer (2011), when showing the importance of local skills to the competitiveness of clusters, point out that deficiency in the structural conditions affect companies. In this way, problems related to racial discrimination, poverty, environmental degradation and ill-health of workers can leave the company less and less connected to the community, diminishing their influence in solving these and other problems. The authors highlight that the maintenance of competitiveness in the framework of the clusters, relates to the investment in the development of product and process technologies.

Knowledge, information, and expertise flow between the organizations that integrate the cluster. This flow occurs through transmission channels (Sohn et al 2016) that promote the Local Knowledge Spillovers (LKS). The LKS are gains in knowledge through the exchange of information without compensation to the source of knowledge, and may happen through intentional interactions (Kesidou & Romijn, 2008).

From studies on the absorption capacity of a wine cluster in Chile, the author Elisa Giuliani (2011) says that the location of specialized activities produce external economies generated by the presence of three factors: availability of local inputs, skilled labor, and knowledge spillovers5. In this context, Giuliani (2011) introduces the concept of Innovative milieu, an informal social relations network in a limited geographical area that enhances the innovative capacity through collective learning processes. Collective learning is a social process in which knowledge transfer mechanisms are social because new knowledge is transferred to other agents, thanks to technological, institutional, and organizational routine and behaviors that facilitate the sharing of knowledge and information.

From dissemination of knowledge, it is possible to identify and analyze the "absorption capacity" of the cluster. Giuliani (2011) considers it the internal capacity of the company to recognize the new knowledge from the external environment, and to apply it for commercial purposes, i.e. a capacity for absorbing, disseminate and exploit creatively all the knowledge acquired by sources external to the cluster. Companies, institutions, research centers, universities and other organizations that are part of a cluster and exposed to these external sources of knowledge are the so-called gatekeepers of knowledge. Gatekeepers of knowledge are organizations and/or individuals that differ from the others by having contact with sources of advanced technical information developed elsewhere, i.e., they filter information and knowledge external to the cluster. Depending on the context, they can be also companies that transfer knowledge extra-cluster to the intra-cluster system. They are organizations able to translate the knowledge acquired into expertise from which other organizations located in the cluster may profit.

The formation of connections with external sources, and the internal structural characteristics of the cluster, are two other factors that are interrelated and comprise the absorption capacity, characterizing it as the ability to establish intra and extra cluster connections. These factors are important for the growth of productivity and exist within buyers, suppliers, and other institutions, contributing to the development (Giuliani, 2011; Graf, 2011).

In studies on clusters, there are two points in the life cycle analysis that are worth attention: one is the level of development achieved; the other is the time to maturity, from the stages wherein informality predominates, up to the maximum level of efficiency where the innovative systems prevail (Cunha, 2003).

For Casarotto and Pires (2001), the cluster develops on the regional vocation downstream (services) or upstream (suppliers), going through different stages throughout its life cycle, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Life cycle of a cluster

| Stage of development | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Pre-cluster | Few companies isolated geared at the same product/service |

| Birth of the cluster | Greater concentration of companies and strong business relationships |

| Development of the cluster | Increase in vertical concentration and early formation of consortia |

| Structured cluster | Local structured system, strong public-private partnership |

Source: Adapted from Casarotto and Pires, 2001 and Menzel and Fornahl (2009)

From the perspective of creation of innovative systems and based on the indicators proposed by EURADA, Cunha (2003) features an analytical framework of the cluster life cycle, which we used as analysis methodology for this research. According to Cunha (2003) there are four categories of clusters, summarized as follows: a) informal cluster: with a predominance of small-sized companies with low qualification of actors, adoption of rudimentary technology, without representation in foreign markets. Poor and unstable economic performance, with companies competing marginally. There is little tendency for cooperation, so there is no entanglement between companies which limits the generation of earnings resulting from the spatial proximity and productive specialization of the companies; b) intermediate stage cluster: composed primarily of small and medium-sized companies, and the technologies adopted are relatively up to date. There are variable performances and the tendency for cooperation is low, as well as the entanglement between firms and the effective cooperation; c) organized stage cluster: hosts a wide variety of structures and business features, however the critical actors adopt modern management practices, with updated technologies. Despite the prevalence of small and medium-sized companies, the presence of gatekeepers and spillovers of knowledge is frequent. The level and potential of cooperation is medium, with unbundling initiatives, however still insufficient to generate gains in productive flexibility and operational efficiency; d) innovative clusters: the requirements for this stage are very strict because it presupposes the unbundling of production, the opening of channels of information, the spillover of knowledge and a high degree of synergy between the different stakeholders of the cluster.

2.1 Tourism cluster

The tourism cluster is composed of a group of companies and institutions related to the tourism product and located in the same geographic region, which seek through joint action, collective gains (Beni, 2003; Martins et al., 2016). In the tourism clusters occur vertical and horizontal type relations between those involved directly and indirectly with the tourism sector (Ashton, Valduga, & Tomazzoni 2015; Tomazzoni, 2015).

Tourism clusters impact positively on regional competitiveness in three ways: 1) by increasing the productivity of companies in a geographic region, promoting access to providers and workers, and the specialized information through inter-organizational relations; 2) defining the direction and pace of innovation to identify specific needs unmet or poorly met; 3) stimulating new businesses (knowledge in real time and anticipation of market trends, conservation among the various institutions in the cluster and flexibility and quick response) (Iordache et al., 2010).

In order to understand the relationship between cluster policies for tourism and regional competitiveness, Ferreira and Estevão (2009) propose a model of analysis of the interactive tourism system with three main components: 1) tourism product, 2) tourism destination and 3) tourism cluster. The proposed model recognizes the role of Governments that define policies that affect the competitiveness of the tourism cluster, and highlights the role of universities as a key strategy for research on the development of innovation and differentiation in the provision of tourism products and services, as well as in training and education of human resources. Polukhina (2016) highlights the need of Government support for initiatives in the tourism centers with better prospects. These centers have the ability to boost the economy of a country and to develop a base of support for other cluster initiatives.

Tourism clusters include: travel agents, tourism guides, suppliers of the national and local hospitality industry, transportation companies, universities, training institutions and other relevant organizations working together, however as competitors, being the main objective of this cooperation the competitive advantage (Cunha & Cunha, 2005; Martins et al., 2016). The tourism cluster differs from other types of clusters, as it relates to the supply of services, i.e. the basic difference lies in the final product of the cluster.

Several factors affect the development of the tourism cluster, such as the infrastructure of the tourist attractions, the tourism traffic, and related support sectors (Tomazzoni, 2015; Martins et al., 2016). However, the most important factor is the cooperation of local authorities, support organizations, scientific research institutions with local small and medium businesses (Yildiz & Aykanat, 2015), and each member is responsible for a specific task in the cluster structure.

Public organizations have important tasks to perform in encouraging the development of tourism clusters, since they are important agents for the promotion of the tourism region. Stands out in this sense, the awareness and contact with companies aiming at the creation and the strengthening of platforms for cooperation. The public organizations are important to foster joint action for the generation of knowledge, innovations, and introduction of changes in the education system to prepare new forms of collaboration (Borkowska-Niszczota, 2015; Tomazzoni, 2015).

The positive impacts arising from the existence of clusters in the tourism industry include the specialization of the companies, effects of scale, the improvement of skills in service provision, fostering synergy advantages between enterprises, the designated coopetition (Santos & Cerdeira, 2013). In addition to these, other positive aspects is the learning process that results from a closer interaction between companies, based on knowledge spillovers (Cunha & Cunha, 2005; Souza & Gil, 2015). The spillovers of knowledge extend the technological competence of the tourism region and of organizations therein (Souza & Gil, 2015).

3 METHODOLOGY

We used exploratory research, which according to Gerhardt and Silveira (2009) helps the researcher to become familiar with the topic, make it more explicit, and enables the construction of hypotheses. Thus, the exploratory research is typically done through literature review and case study (Prodanov & Freitas, 2013).

This study uses a qualitative approach, which "doesn't care about numerical representativeness, but with the deepening of the understanding of a social group, or an organization" (Gerhardt & Silveira, 2009, p. 31).

Lubeck, Wittmann and Silva (2012) indicate the relevance of the use of qualitative methodology in research to identify and classify clusters. The authors highlight the importance of presenting information to demonstrate the existence, efficiency and effectiveness of cooperative activities between companies.

The present study sought to raise evidence that there is a concentration of businesses and other organizations, as well as an infrastructure geared to the tourism in the city of Balneário Camboriú. To achieve this objective, we used as framework the cluster concepts through the geographical location and focus of productive specialization (Porter, 2008; Sölvell, 2008; NIE & Sun, 2015) and aspects associated with specialization in the tourism sector (Tomazzoni, 2015; Martins et al., 2016; Polukhina, 2016).

In order to describe the elements that constitute the cluster of Balneário Camboriú, we adopted as technical procedures documentary and literature review. The literature search provided references on the topic that have already been published and thus brought us a large amount of information and prior knowledge about the search problem (Gerhardt & Silveira, 2009). Documentary research complemented and enhanced literature review, through materials without statistical treatment (Gerhardt & Silveira, 2009).

For data collection, we conducted contacts with: 1) the Municipal Secretary of Tourism and Economic Development of Balneário Camboriú (SECTUR); 2) the Association of Hotels, Restaurants, Bars and similar establishments of Balneário Camboriú (SINDISOL); and 3) the University of Vale do Itajaí (UNIVALI), entities related to the hospitality industry in Balneário Camboriú. We collected other information through national and international organizations reports such as the United Nations Development Program. Researchers prepared the script for data collection considering information about: 1) lodging establishments 2) food and beverage services, 3) travel agencies; 4) infrastructure for events, 5) existence of training facilities (universities, colleges, training and qualification centers, and research centers) and; 6) number of jobs linked to the tourism sector and the average remuneration per person. The collection and analysis of these data occurred between the months of March and May 2016.

Considering the importance of cooperation and collective earnings within clusters presented in literature (Giuliani, 2011; Sohn et al., 2016) we present and analyze two events related to the tourism sector carried out in the city. We examined the cases of Tasty Balneário ('Balneário Saboroso') and the Scientific Forum on Gastronomy, Tourism and Hospitality (FCGTURH). The selection of these events came about because of their importance to the sector and their distinct natures. The first is an event supported by food and beverage establishments, being a purely business event aiming to promote and increase the flow of tourists to the region. The second event is of a technical and scientific nature and aims to contribute to the development of relationships between companies, the Government and universities.

For the collection of information on tourism-related organizations clusters and inter-organizational cooperation in the municipality of Balneário Camboriú we followed the model proposed by Cunha (2003) (see Table 2) to guide the analysis. We chose this analysis model because it is based on the criteria used by EURADA in research for classifying and assessing the performance of productive clusters in the European Union, whose clusters are already consolidated and even undergoing restructuring. In this sense, we highlight two important aspects, the presence and the activity of gatekeepers of knowledge (Giuliani, 2011; Guo & Guo, 2011; Sohn et al., 2016). With regard to the procedures of analysis, the methodology of Cunha (2003) classifies the clusters in four degrees of maturity: informal, intermediate, organized, or innovative.

Table 2 Clusters and their characteristics in the different levels of maturity

| Classification | Characteristics |

| Informal cluster | Predominance of small-sized companies with low qualification of critical actors, rudimentary technology adoption, without representation in foreign markets. Poor and unstable economic performance, with companies competing marginally, little propensity to cooperation; there is no interconnection between companies. |

| Intermediate stage cluster | Predominance of small and medium-sized companies, and the technologies adopted are relatively up to date. There are different performances and the tendency for cooperation is low, as well as the entanglement between companies and the effective cooperation. |

| Organized stage cluster | Hosts a wide variety of structures and business features. The critical actors adopt modern management practices, with updated technologies. Despite the prevalence of small and medium-sized companies, the presence of gatekeepers and spillovers of knowledge is frequent. The level and potential of cooperation is medium, with unbundling initiatives, however still insufficient to generate gains in productive flexibility and operational efficiency. |

| Innovative cluster | Presupposes the unbundling of production, the opening of channels of information, the spillover of knowledge and a high degree of synergy between the different stakeholders of the cluster. |

Source: Adapted from Cunha (2003)

4 DESCRIPTION OF THE CONSTITUENT PAR-TS AND ANALYSIS OF THE CHARACTE-RISTICS AND ATTRIBUTES OF THE CLUSTER

The city of Balneário Camboriú is known as the Tourism Capital of Santa Catarina. The municipality has a high level of development, given that according to data from the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) in partnership with the Institute of Applied Economic Research (IPEA), it presented in 2013 the second best HDI in the State, with a GDP per capita of R$ 22,328.

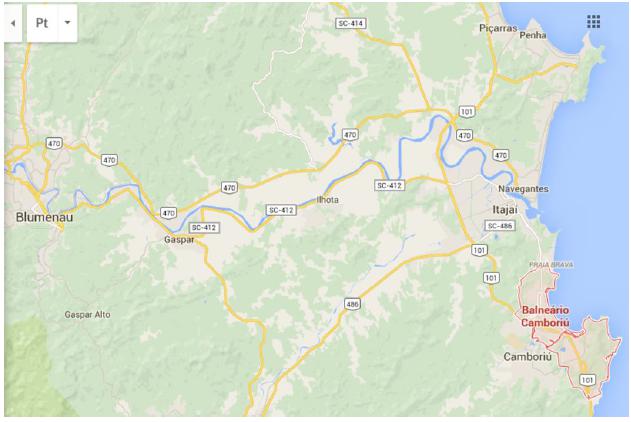

Located next to major cities in the State of Santa Catarina, such as Florianópolis, Blumenau and Joinville, it has three airports in the vicinity (located in Florianopolis, Navegantes and Joinville). The access to the municipality is by the BR-101 considered as one of the best roads of Brazil.

As depicted in Figure 2, the municipality is neighbor to cities that host important events at national level, such as the Oktoberfest (held in Blumenau) and the Volvo Ocean Race (held in Itajaí) and also internationally recognized tourism attractions such as Beto Carrero World (a theme park located in Penha) and the night-club Green Valley (located in Camboriú)

Balneário Camboriú is the ninth favorite city by foreigners for tourism in Brazil, according to the Ministry of Tourism (2015). It was considered one of the 65 inductors destinations in Brazil (Brasil, 2014) and meets a demand of 600,000 visitors per month from December to February and about 200,000 in the remaining months of the year (Prefeitura Municipal de Balneário Camboriú, 2016).

To meet visitor needs in the high season, and minimize the effects caused by the seasonality of tourism, Balneário Camboriú has developed a relevant infrastructure of products and services, designed to attend the tourism activity. Hotels, travel agencies, providers of food service, transportation and events, among others, compose the tourism infrastructure to meet the demand of services aimed at health and well-being, events, tours, radical rides, cultural events and organized nightlife (Prefeitura Municipal de Balneário Camboriú, 2015).

With regard to the lodging provided in Balneário Camboriú, the city has more than one hundred companies in the sector, among resorts, hostels, excursion houses, inns and, particularly, hotels. Of the total, the town has 7,734 accommodation establishments resulting in 19,034 bed spaces to meet visitors' demand (Prefeitura Municipal de Balneário Camboriú, 2015).

The city has a wide variety of food and beverage establishments. According to the Municipal Tourism Plan of Balneário Camboriú (2015) there are 331 establishments (Table 4).

Table 3 Lodging in Balneário Camboriú (SC)

| Lodging in Balneário Camboriú | |

|---|---|

| Hotels | 76 |

| Resorts | 1 |

| Inns | 25 |

| Hostels | 4 |

| Excursion houses | 21 |

Source: Municipal Tourism Plan of Balneário Camboriú 2015-2025 (2015)

Table 4 Food and Beverage options in Balneário Camboriú

| Food and Beverage Services | |

|---|---|

| Restaurants and bars | 178 |

| Cafés/Bakeries | 90 |

| Steakhouses/ Grill Restaurants | 22 |

| Pizzerias | 41 |

Source: Municipal Tourism Plan of Balneário Camboriú 2015-2025 (2015)

In Balneário Camboriú there are 18 squares for outdoor activities, 14 leisure equipment, 10 cultural attractions, gastronomic, cultural and tribute events and 14 monuments in tribute to various legends and local personalities.

The nightlife complex groups 106 establishments, being 82 bars and beer halls and 10 nightclubs (counting with some national party events). Nightclubs such as Green Valley stands out, voted the second best club of the world's electronic music in 2016 by DjMag magazine, specializing in the area (DjMag, 2016).

Tourism in Balneário Camboriú has scenery roads amid the Atlantic Forest on the route of the highway 'Interpraias', which connects Balneário Camboriú to the neighboring municipality, Itapema. This highway reveals unique landscapes with access to six beaches belonging to the municipality: Laranjeiras Beach, Taquarinhas Beach, Taquaras Beach, Pinho Beach, Estaleiro Beach, and Estaleirinho Beach. Besides the beaches, the city offers a range of tourism attractions such as: Unipraias Park, Natural Park Raymond Malta, Christ Light, Runway of Pontal Norte, Morro do Careca, Barra Sul Pier, Cyro Gevaerd Park.

Balneário Camboriú has 56 travel agencies registered in the Brazilian Register of Tourism Companies [CADASTUR] in 2016, acting as tour operators, travel agencies and inbound tourism agencies in the locality. The municipality also has five event planners and four available venues (Prefeitura Municipal de Balneário Camboriú, 2015).

There are 21 associations and 7 unions in the municipality, composed of entities related to the tourism sector, in addition to 74 tourist guides. The municipality also has a considerable number of institutions of higher education (undergraduate, postgraduate, MBA, MSc and PhD) adding up to ten institutions holding a large number of programs. The information on the websites of educational institutions refer that all of them offer programs in areas related to tourism, such as management, marketing, accounting and others. It is important to note that the University of Vale do Itajaí [UNIVALI] offers various levels of education in tourism and hospitality: undergraduate, Master's and Doctoral degrees.

Beyond the relevant aspects of local identity and cultural appreciation, and options of products and services, ensuring competition and local free trade, tourism is important to boost economy of Balneário Camboriú, mainly regarding the generation and provision of jobs and income for the local community. As set out in Table 7, the activity generates on average 10,254 direct jobs (Prefeitura Municipal de Balneário Camboriú, 2015).

Table 5 Event related services in Balneário Camboriú

| Events in Balneário Camboriú | |

|---|---|

| Event planners | 4 |

| Venues for events | 5 |

| Bars and Breweries | 82 |

| Sport Bars | 7 |

| Private Nightclubs | 7 |

| Nightclubs/discos | 10 |

Source: Municipal Tourism Plan of Balneário Camboriú 2015-2025 (2015)

Table 6 Educational institutions in Balneário Camboriú

| Instituition | Administrative Dependency |

|---|---|

| Faculty AVANTIS and Higher Institute of Education AVANTIS | Private |

| Faculty SOCIESC of Balneário Camboriú | Private |

| University of Vale do Itajaí - UNIVALI - Balneário Camboriú | Private |

| University Center Leonardo Da Vinci - UNIASSELVI - Balneário Camboriú | Private |

| Faculty of Litoral Catarinense | Private |

| University Castelo Branco - Campus Balneário Camboriú | Private |

| University Paulista - Campus Balneário Camboriú | Private |

| University Anhembi Morumbi - Campus Balneário Camboriú | Private |

| University Center of Maringá - Campus Balneário Camboriú | Private |

| State University of Santa Catarina6 - UDESC | State |

Source: State Secretary of Education of Santa Catarina

Table 7 Direct jobs generated by tourism in Balneário Camboriú and average income salary

| Jobs linked to tourism in Balneário Camboriú | ||

|---|---|---|

| Sector | Number of jobs created | Average salary/person |

| Road passenger transport | 580 | R$ 1,575.30 |

| Other road transport | 41 | R$ 4,712.50 |

| Unspecified transport activities | 155 | R$ 3,156.67 |

| Marine transport | 73 | R$ 2,936.57 |

| Air transport | 21 | R$ 1,150.00 |

| Auxiliary transport activities and activities related to the organization of cargo transportation | 445 | R$ 4,971.16 |

| Lodging | 1150 | R$ 1,409.78 |

| Restaurants and other food and beverages establishments | 2745 | R$ 1,414.18 |

| Catering services, buffet and other prepared food services | 300 | R$ 1,316.90 |

| Street food | 31 | R$ 1,766.67 |

| Unspecified food services | 704 | R$ 1,513.75 |

| Cinematographic activities, production of videos and television programs, music and sound recording | 62 | R$ 1,433.33 |

| Real estate activities | 1088 | R$ 2,519.62 |

| Travel agencies, tour operator and booking services | 311 | R$ 1,634.33 |

| Call center activities | 31 | R$ 3,000.00 |

| Events organization activities, except cultural and sports events | 21 | R$ 1,518.50 |

| Other supply services activities, particularly to companies | 228 | R$ 1,932.86 |

| Other educational activities | 352 | R$ 1,603.24 |

| Unspecified educational activities | 352 | R$ 1,929.41 |

| Artistic, creative and performative activities | 580 | R$ 2,215.93 |

| Cultural and natural environment activities | 10 | R$ 2,000.00 |

| Gambling activities | 62 | R$ 1,750.00 |

| Sports activities | 218 | R$ 2,334.29 |

| Physical fitness activities | 228 | R$ 1,997.73 |

| Recreational and leisure activities | 466 | R$ 1,584.00 |

Source: Municipal Tourism Plan of Balneário Camboriú 2015-2025 (2015)

It is worth mentioning that the municipality of Balneário Camboriú (Santa Catarina) has implemented a formal policy to raise awareness of tourists on how to respect the local community/destination. Municipal authorities carry out programs to encourage the use of tourism facilities by the local population. The report of the National Tourism Competitiveness index (Brasil, 2014) shows the result of this policy. This index emphasizes the regional cooperation dimension, in which Balneário Camboriú has obtained one of the best performances among the capital cities. It measures cooperation through the evaluation of regional governance, regional cooperation projects, regional tourism planning and the integration of tourism promotion and marketing strategy. The national average for regional cooperation reached 48.3 points and Balneário Camboriú obtained 70.1 points. In the general ranking, Balneário Camboriú is among the 15 best tourism cities in the country, with 69.9 points. The score is above the average of Brazil (59.5 points) and even above the average of the state capitals (68.2).

The implementation of strategic actions to encourage regional cooperation and collective gains stands out. In this sense, we highlight two important events for city: Tasty Balneario and the Scientific Forum on Gastronomy, Tourism and Hospitality (FCGTURH).

The Tasty Balneario, in its seventh edition in 2016, is an event promoted by the Balneário Camboriú Convention & Visitors Bureau. The event aims to promote regional tourism by means of local cuisine, giving more visibility to the destination. Thirty-eight restaurants and bars attended last edition by offering a full menu with starter, main course and dessert, for a fixed price. Among the supporters of the event there are important companies located in the region and working in different sectors, the City Hall, entities such as SEBRAE Santa Catarina, and educational institutions like UNIVALI. The results of the accountability of the seventh edition, which took place in July 2016, submitted a record of 14,183 sold menus.

In its seventh edition, the event featured two novelties, a social action to collect food and the mystery shopper. Thus, through a partnership with the Lions Club of Balneário Camboriú more than 200 kg of non-perishable food was donated to the Drug and Alcohol Addiction Rehabilitation Center of Camboriú. The participation of the company Mister O, which provides mystery-shopping services, has collected information on the quality of the menu, and revealed that the best-rated aspect was the cost-benefit ratio. This is due to the quality of the dishes, creative menus and attractive parallel activities (Balneário Saboroso, 2016). In this context, we can consider that the event Tasty Balneario generates agglomeration economies.

Given the above mentioned, we consider that the Balneario Camboriu Convention & Visitors Bureau, through Tasty Balneario encourages the cooperation and coordination between firms that operate in the same segment, promoting coopetition (Nalebuff & Brandenburger, 2011). The results taken from the previous four editions show that the event produces external economies generated by three factors: availability of local inputs, skilled labor, and knowledge spillovers (Giuliani, 2011).

The academic-oriented events that happen in the most important University of the cluster, the Universidade do Vale do Itajaí (UNIVALI) highlight the integration between the actors. In this sense, we refer the Scientific Forum on Gastronomy, Tourism and Hospitality (FCGTURH), which started in 2012. The goal of FCGTURH is to foster the debate on tourism development combined with hospitality and cuisine from all perspectives, enabling the development and connection of the various actors, encouraging the integration between the academia, society and Government and socializing theories of tourism and food. Participants in the event were researchers from the fields of tourism, hospitality and gastronomy of Brazil and abroad that communicate the results of their researches and discuss trends in these areas. Since its first edition, the FCGTURH includes the ST&I community interested in discussing topics related to governance and regional development and for companies that want to learn about research in the areas of tourism, hospitality and food in order to apply them in their niche market. During the past editions of the event, besides the organization linked to the University of Vale do Itajaí (UNIVALI), other important partners supported the Forum. It is the case of tourism-related organizations in Balneário Camboriú, government agencies that fund research and technological development such as the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel [CAPES], the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development [CPNQ], the Ministry of Education, and the Brazilian Association of Bachelors of Tourism [ABBTUR].

In previous editions, several renowned researchers in the field of tourism and hospitality participated in the Forum. Among them, we highlight the presence of Jafar Jafari, PhD (Wisconsin University, USA), João Albino Matos da Silva, PhD (University of Algarve, Portugal), Miguel Moital, PhD (Bournemouth University, UK), Anita Eves, PhD (Surrey University, UK). These researchers presented papers on Innovation in Food, enabling an environment conducive to the spread of knowledge and opportunity for debating local, regional and State food-based tourism.

Given its role in the formation of skilled labor for the tourism sector and through the FCGTURH, UNIVALI is considered a gatekeeper of knowledge in the tourism cluster of Balneário Camboriú. The institution demonstrates the ability to recognize new knowledge from the external environment and contributes to dissemination so that it can be applied for commercial purposes (Giuliani, 2011; Hortelano, Pérez, & Villaverde, 2015). The Forum also promotes the spillover of knowledge through interactions (Kesidou & Romijn, 2008).

Through a comprehensive analysis of the events studied, we consider that the Tasty Balneario and the FCGTURH create and strengthen platforms for cooperation between companies and institutions, generating knowledge for the tourism sector (Borkowska-Niszczota, 2015).

As general findings, we highlight:

- In relation to the event Tasty Balneario, the creation of a new menu and the increase in sales show the positive impacts of coopetition that occurs within the cluster. Among these impacts, we refer fostering innovation and increasing the productivity of companies, and the knowledge of market trends (Iordache et al., 2010; Guo & Guo, 2011; Sohn et al., 2016).

- In relation to FCGTUHR, UNIVALI develops contacts with external sources of knowledge, such as researchers located abroad (e.g., Portugal, Spain, United Kingdom), acting as gatekeeper of knowledge in the tourism cluster of Balneário Camboriú by promoting the formation of linkages intra and extra cluster (Giuliani, 2011).

- Both events promote collective learning, and can be considered knowledge transfer mechanisms of the cluster (Giuliani, 2011; Graf, 2011).

The results depict the presence of a cluster of companies, organizations and infrastructure operating in the tourism sector located in Balneário Camboriú, and there is evidence of inter-organizational cooperation aimed at collective gains and the development of the sector in the region. Based on the concepts of Tomazzoni (2015), Martins et al., (2016), and Polukhina, (2016) we confirm the existence of a tourism cluster in the city of Balneário Camboriú.

Given the above mentioned and based on the cluster analysis model proposed by Cunha (2003) we considered Balneário Camboriú an intermediate stage cluster, with tourism bringing positive impacts to the region. We noticed that there is a tendency to cooperation. In this sense, we can also identify in the cluster characteristics related to organized clusters, with the presence of gatekeepers and spillovers of knowledge (Giuliani, 2011).

5 FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

As a result, we consider that Balneário Camboriú is a tourism cluster. The data confirm the presence of components of tourism clusters including the geographical proximity and cooperation of the following critical actors: companies (lodging, food and beverage services), government entities, universities and institutions, leisure equipment, agencies, and tourism attractions.

The tourism cluster of Balneário Camboriú provides favorable conditions for generating collective competitive advantages, and strengthening tourism in the region. In this way, the implementation of strategic actions that aim to encourage the collaboration, such as the "Tasty Balneário" and the "Scientific Forum on Gastronomy, Tourism and Hospitality (FCGTURH)".

From this study, several findings emerged leading us in search of answers summarized in these conclusions. The research work clarifies questions, broadens the scope and brings up new possibilities and research opportunities. These opportunities can be related to improvement of research technique adopted, or to the model of analysis. In this sense, aiming at the improvement of the methodology of analysis adopted in this paper, we suggest its application in other cases of tourism clusters in Brazil and abroad. We also suggest further studies on the tourism cluster of Balneário Camboriú, e.g., an analysis of its dynamics.

Finally, we emphasize that the results obtained in surveys like this, could not be generalized, by the very nature of the subject and the methodology used, but they serve as insights that can be extended to other clusters and inter-organizational networking modalities in the tourism sector.

texto em

texto em